News

Deportation Journeys Wind Through Ohio Detention Facilities

By: M.L. Schultze | WKSU

Posted on:

Ohio is far from the U.S. southern border, but the policies and practices there are playing out here daily. The Cleveland Immigration Court has a caseload numbering in the thousands. Ohio jails and private prisons are collecting millions of dollars to house immigrants. And immigrant families who have lived in Ohio for years are planning their departures. Ohio is playing a big role in the national immigration debate.

On one wall of the commissary in the Geauga County jail — across from the Ramen noodles and orange gym shoes — is a rack with a half-dozen suitcases, each containing the worldly possessions of someone about to be deported.

Jail Administrator Lt. Kathy Rose says the bags are one sign departure is just weeks, days, even hours away. Another sign is the last visits she arranges between those facing deportation and their families.

“They get to sit in one of those multi-purpose rooms with that person. But we’re very clear on the rules,” she explains. Hugs are allowed as a greeting and goodbye, but no more. She acknowledges it’s tough to witness, especially when children are involved.

Ohio is 1,600 miles from the U.S. southern border, but the policies and practices there are playing out here daily. According to the Syracuse University TRAC database on immigration, the Cleveland Immigration Court, which covers the entire state, had 3,699 new immigration cases filed through June. If the pace continues, it will climb to nearly 5,000 cases by the time the fiscal year ends in September.

Monthly snapshots from the TRAC reports show the number of immigrants in Ohio jails and private prisons has more than doubled since the last months of the Obama administration, largely because of a new federal contract with CoreCivic, which operates the private prison in Youngstown and has come under fire for its border operations.

Meanwhile, though Immigration and Customs Enforcement brings many of the detainees from elsewhere, immigrant families who have lived in Ohio for years are also planning their departures.

Detention Facilities

Geauga is one of five Ohio lockups housing immigrants awaiting asylum claims or facing deportation. The others are in Seneca, Butler and Morrow counties and the private prison in Youngstown. Since September of 2017, the five facilities have been housing 500 to 600 people in ICE custody per month.

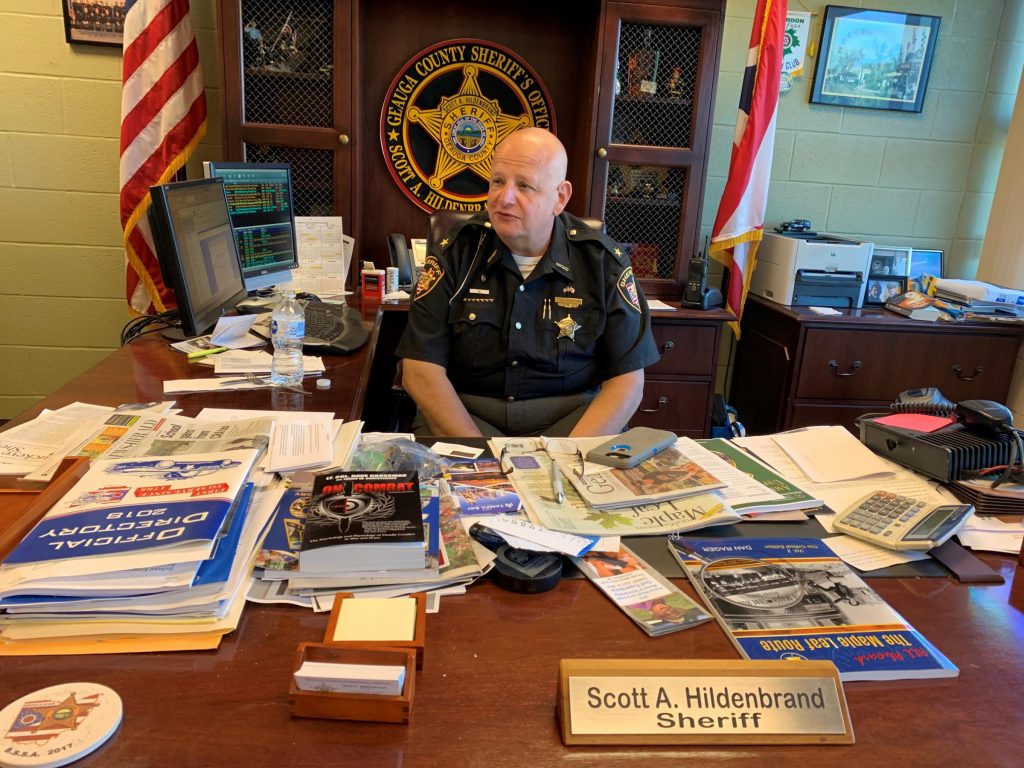

He notes his jail began housing immigrants before Donald Trump became president and his immigration policies took effect.

“Immigration sends us the detainees and we house them for them. It’s not our job to figure out if that was the right thing to do or the wrong thing to do,” he says.

Geauga generally houses 40 to 50 people a day. About 90 percent are men; more than half have no previous criminal records; most face final orders of deportation — though for some, those orders had been on hold for years.

The Geauga facility bears no resemblance to the images of squalid and overcrowded border camps that have dominated the national news. Jail administrator Rose shows off a pristine kitchen (“the largest restaurant in the county,” she jokes), open dorms, rec rooms, and a medical clinic.

She says her jail treats everyone equally.

“Regardless of if they’re out of common pleas, muni courts, if we’re holding them for another agency (or) they’re immigration, they’re all human beings,” she says.

But, there are differences. We step into a room, with a single chair in front of a small black screen. This is immigration court.

“The federal court in Cleveland has a video connection with us so they dial in on the mornings that we have court,” Rose explains.

The video link is often the only connection between the judges in Cleveland and the men and women whose asylum and deportation cases they’ll decide.

Interpreters are patched in to the hearings, but the people in detention often are in the room alone. Technically, this is a civil proceeding. So unlike in criminal cases, detainees get no lawyer unless they pay for them or find a volunteer.

And the vast majority of those cases will end in their removal from the country, either through deportation or what’s considered voluntary departure.

Seeking Asylum

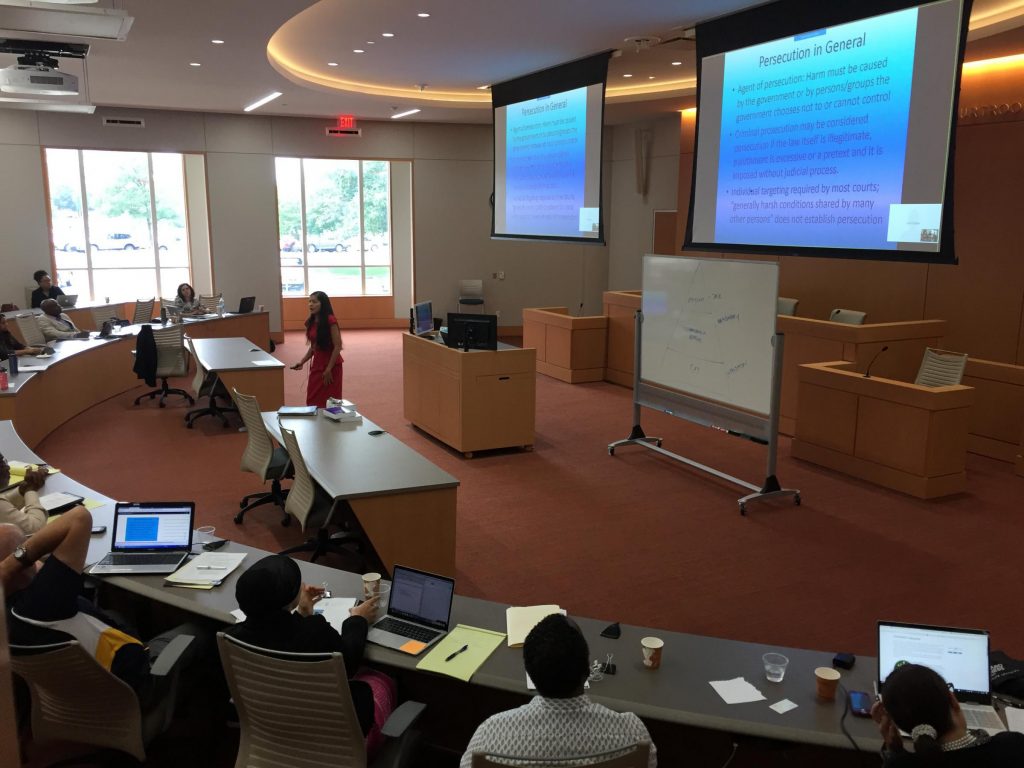

Elizabeth Knowles’ immigration clinic at the University of Akron specializes in a subset of the immigration cases: asylum cases. They’re people who under international and U.S. law can show that returning to their home countries could be, literally, deadly. They account for less than 5 percent of the cases in Ohio.

“They have to fear returning to their home country because of persecution by a government actor based on their race, religion, nationality, political opinion or that they’re a member of a particular social group and that they cannot avail themselves of the protection of their own govt. It’s a long definition, but its a narrow definition,” Knowles said.

In the best of times, she says the process often means months waiting in jail, though these are “people who haven’t broken the law, who are trying to get protection that they’re entitled to seek.”

The Syracuse database shows just 20 percent of the asylum cases filed in Ohio from 2013 to 2018 were granted by the four immigration judges in Cleveland.

Knowles says some of her clients with strong asylum claims have simply given up rather than remain in jail.

Deportation Looms

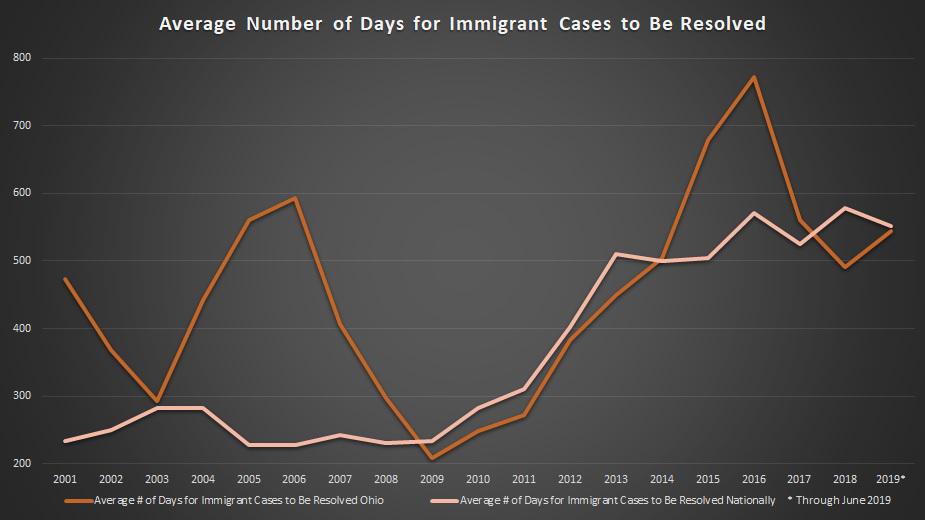

On a broader level, Knowles — like most immigration advocates — acknowledges problems with the immigration system preceded President Trump. Over the last decade, many advocates described it as a broken system, and caseloads and wait times soared in 2016.

“It’s just becoming more and more adversarial in everyway possible,” she says. “There’s a lot more hard lines coming from upper ICE folks. Even where people at the local level might want to negotiate, they’re prevented from doing so by higher ups.”

And perhaps most damaging, she asserts, is a tone that dehumanizes immigrants — whether they’re newcomers who are openly seeking asylum or people who slipped without authorization into the country more than a decade ago. (The TRAC snapshots show a quarter to nearly half of those held in Ohio jails and prisons have been in the U.S. for 10 years or more.)

If trends hold, four-out-of-five of the immigration cases decided in Cleveland will end with people being shipped out. The greatest number of them are Guatemalans, Mexicans and Hondurans, people like Patrona, who requested we use only her first name.

Her husband and young son, Sam, had entered the U.S. without authorization about four years ago. Gangs in Guatemala, she says, were threatening to kill them if he didn’t turn over proceeds from his trucking business. She joined her husband in Ohio two years later, and they now have a 2-year-old American-born daughter.

But her husband was taken into ICE custody during one of his regular check-ins two years ago — then jailed and deported.

“It completely destroyed our life,” she says through an interpreter who speaks her derivation of an ancient Mayan language. Like many Guatemalans in Ohio, her native language is not Spanish.

That means much of Patrona’s navigation of the immigration system now relies on her now 12-year-old son, Sam. He’s trilingual, an avid “Fortnite” player and hopes to be either a soccer player or a lawyer.

He remembers the day his father disappeared from his life. “I cried, and I think I didn’t eat for like a week,” he said. “I loved my dad, and he loved us.”

Sam’s mother still attends her bimonthly ICE check-ins. She hopes to convince people she’s a good person who wants “to be a good role model for others.”

But she’s also expecting her own deportation and making arrangements to take her son back to a country he barely remembers and her daughter — an American citizen — to a place she’s never been.