News

At This Dayton Camp, Children Of The Opioid Crisis Learn To Cope And Laugh

By: Kavitha Cardoza | NPR

Posted on:

Editor’s note: To protect the anonymity of the children in this story, we are not using their names.

Children are often called the hidden casualties of the opioid epidemic. They carry a lot of secrets and shame.

The majority of children at Camp Mariposa in Dayton, Ohio, have parents who are addicted to opioids. The nonprofit group Eluna runs camps in 13 states, many of them in areas hardest hit by the opioid crisis. All of these children have experienced trauma, sometimes abuse and neglect, and a growing number are in foster care. These children often struggle to reconcile the loving parents they remember with who they have become.

One of them is 8-year-old C.

“When my sister and my brother were kids, my mother would actually beat them,” C says. “Like child abused them. My brother and sister were just screaming and crying. ‘Cause actually my mom holded my sisters and choked her, up to where her feet were off the ground. It made me feel mad at my mom. I still don’t forgive her, but I still love her.”

C’s mother lives in a different state and has lost custody of all four of her children. C lives with their grandmother.

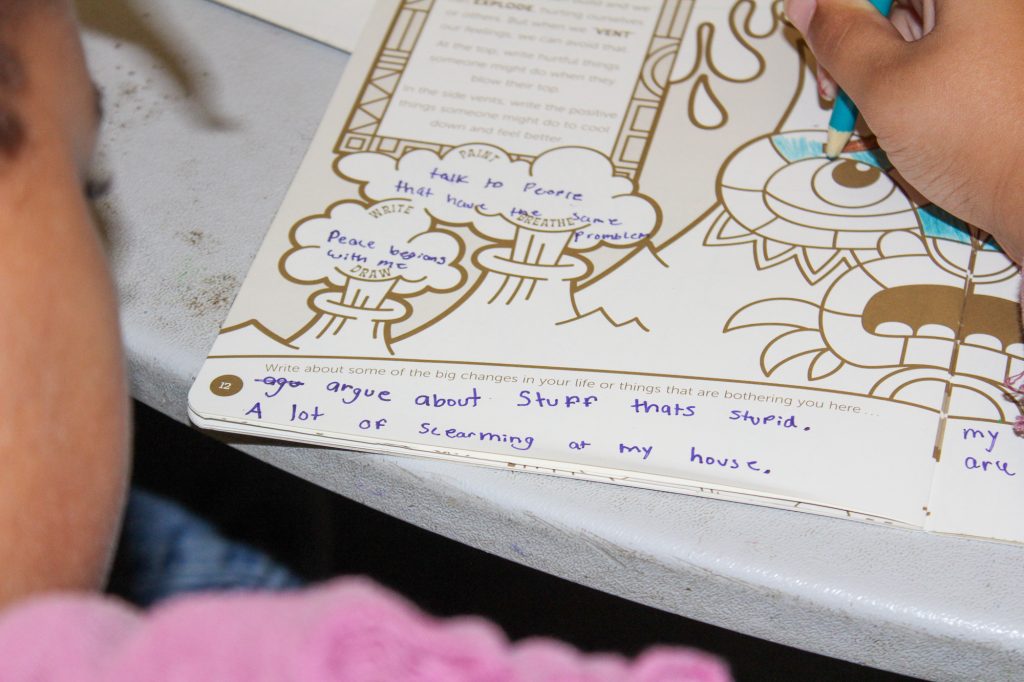

These children often think they’re alone in their experiences, and Camp Mariposa allows them to connect with other children. Their lives are filled with uncertainty, but camp director Wendy Berkshire wants these preteens to know they do have power.

“To know they can’t control what’s going on in their life or their family, but they have all the power to control themselves and their emotions,” Berkshire says.

Protective influences

“Gently put the glitter in. There’s blue, purple, pink and white glitter,” Berkshire says as she teaches the kids to make mindfulness jars. They mix a few drops of food coloring to their glass jars that are filled with a mixture of water and glue. Then they add glitter.

The jar has a pretty simple idea behind it: When you shake it, your thoughts and feelings are like the glitter — agitated and all over the place. Stop shaking and the glitter settles down. You can, too. A, 12, stares at their jar.

At Camp Mariposa, children are encouraged to share their feelings. B, 12, talks about coming home from a play date and being taken away to foster care. Since then B has been in several foster homes.

“When it happened again, I had a mental breakdown,” B says. “And I got anxiety and got depression.”

S wants to forget seeing their mother do drugs while pregnant.

“It made me upset because she almost made my brother die,” S says.

A shares that their mom has relapsed.

“She says it’s like a grip it has upon you,” A says. “She explained it to me and my brother, like if you really want to have a cupcake every single day and constantly. And if you didn’t have it, you’d feel really sick.”

Camp mentor Derek Fink hears painful stories all the time.

“These kids have experienced needles in their living room and having to call 911 to revive their parents,” Fink says. “Kids living in garages, peeing in buckets in the corner. Kids sticking up for their parents because they want them to do right. Kids watch their dads [overdose] and die, to raise their own brothers and sisters because there’s no parent in their life.”

Having caring adults such as Fink around, is a way to boost protective influences in their lives. The children are paired with mentors they meet every month, either at camp or weekend activities for at least a year. B says at camp, they know they belong.

“Like, this is my home and … my other home at home, is like a backup,” B says.

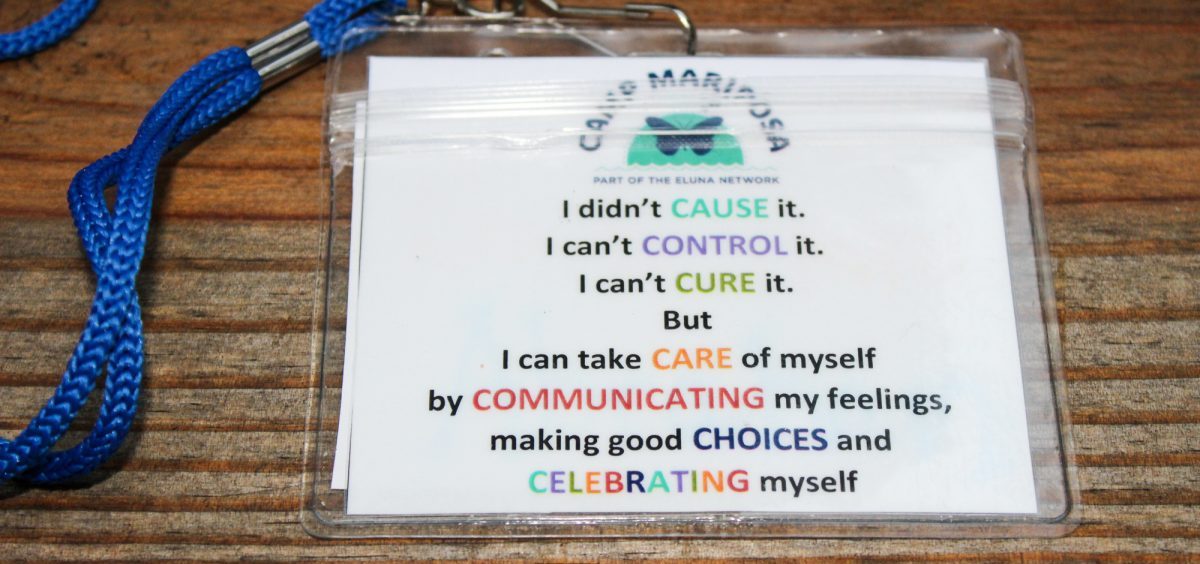

Children learn how to calm themselves down when they’re upset, they take healthy risks through activities such as horseback riding and singing the camp song — “I didn’t cause it, I can’t control it, I can’t cure it.”

B loves the song.

“It helps me realize that I didn’t cause what happened to me and I used to think that all the time,” B says. “I used to be like, ‘I shouldn’t be here, I caused this.’ Now I realize that it wasn’t me and it makes me feel much better.”

Stolen childhood

These children are at higher risk for using drugs themselves and for entering the juvenile justice system. Brian Maus, the director of addiction prevention and mentoring programs at Eluna, says they did a three-year study with a team of researchers at Louisiana State University. They found both their main goals were being met: 95% of campers had never used a substance to get high and 98% had no involvement in the juvenile justice system.

“Ultimately the goal is to break the cycle of addiction,” Maus says.

The camps are funded through government money and private donations, and the need is so great they are opening camps in five additional locations next year, including in Alaska and Texas. A second camp will open in Dayton.

Maus, who is a former therapist, says one the best things about this camp is that kids can be giggly and goofy here. They pour too much syrup on their pancakes, yell about spotting a spider and are looking forward to a big camp party tonight, complete with a deejay and s’mores.

“I think the education is great. I think the connections are awesome,” Maus says. “But to let kids be kids? That’s it for me. The opioid epidemic really has stolen their childhood away.”

Letters to addiction

But before that, they need to tackle some difficult stuff.

The children have written “Letters to Addiction” and they’re getting ready to read them out loud. The lights are dim and the children are uncharacteristically somber. C begins.

Dear Addiction,

Why do adults like you? When I am older I will be against you. You make me not like my mom and dad and its sad. You made my dad go to prison. I hate you.

D is next.

Dear Addiction,

You are my worst enemy. You took my dad from me, my stepdad, my aunt and about to be my uncle. So I just have to ask you a question: Can you please just go to hell?

Signed, a very sad kid.

I hate you so f*****g bad. I wish you wasn’t real. You hurt kids so bad.

Soon, everyone is crying. But it’s cathartic and later on the children say this was the best part of camp.

Camp director Wendy Berkshire and all the mentors hug and high five them as each child throws their letter into a fire pit. There are lots of “I love yous” and “You are so brave” and “I’m proud of yous” as the children run off to play.

Ten-year-old D is the last one. He throws his letter in and looks up, his big blue eyes filled with tears and says softly, “I miss my mom.”

9(MDI4ODU1ODA1MDE0ODA3MTMyMDY2MTJiNQ000))