Culture

When Your Lost Relative Turns Out to Be a Monumental Artist

By: Emily Votaw

Posted on:

It was initially a moment of existential quandary that led Amanda Gormley to unearthing the life and legacy of artist and illustrator Barbara Shermund. The artist is Gormley’s aunt, and her illustrations were a crucial component of defining the style of The New Yorker long before it was a household name. Shermund’s work is currently being celebrated at the Decorative Arts Center of Ohio’s Tell Me a Story Where the Bad Girl Wins: the Life and Art of Barbara Shermund virtual exhibition.

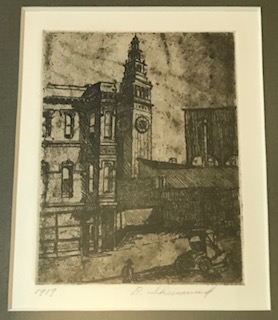

After the passing of her brother in 2010 Gormley found herself overcome with grief at her dining room table, and it was in that moment that she began examining a series of framed etched plates that she had hung in her home after her father’s passing 13 years prior. Although he didn’t express to know much about the plates other than that they were made by Barbara Shermund, an artist from his ex-wife’s side of the family, he did instruct Gormley to save them, so she did. Little did Gormley know that she was about to go on a nearly decade long research endeavor that would illuminate Shermund’s fascinating career: from her time spent as a cartoonist at The New Yorker in its earliest incarnation, to her work in publications such as Esquire, Collier’s and others — as well as the commercial illustrations she provided for a wealth of products, and myriad book illustrations.

“I was looking at Barbara’s artwork and I said, ‘I’m a career investigator, why don’t I know more about you?’ It was like a light bulb turned on,” Gormley said. “I looked up and said, ‘This is my career case.’”

“The first step was to find out where she was buried, because I felt that I was an interloping relative who was going to start poking around in her personal life, and I felt that I needed to apologize for my absence and ask permission,” said Gormley. “I felt it was necessary to find out where she ended up before I could go back to where she started.”

However, Gormley couldn’t seem to find Shermund’s obituary, nor information on where she could have been buried. By 2013, Gormley had been contacting funeral homes throughout New Jersey, where she had reason to suspect Shermund would be buried, and she finally called one that informed her that not only did they cremate Shermund after her passing in 1978, they still had her ashes because no one had ever come to pick them up.

“I was crestfallen. I couldn’t believe what he was saying,” said Gormley. “In part, I found her and I was happy, but I was devastated that she was still in the same temporary cremation canister from 1978.”

Gormley then found that Shermund’s mother was buried in an unmarked grave on the outskirts of San Francisco. Shermund’s mother had tragically passed away during the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918, while Shermund was studying art at the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco. Although Gormley found evidence to suggest Shermund took a brief hiatus after her mother’s passing, Shermund was soon back to her craft, living with her father and perhaps inspired by looking back at her father’s architectural prowess in the aftermath of the 1906 earthquake that had devastated the city when Shermund was only seven years old. One might draw parallels between the ways in which the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic made an enduring mark on Shermund’s life and the ways in which the current coronavirus pandemic has impacted the trajectory of the current exhibition of Shermund’s work curated by Caitlin McGurk of the Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon Museum.

Interestingly, the etchings that served as the springboard for Gormley’s investigation into the life of her aunt also might have served as a very significant catalyst for Shermund’s career. Gormley would find out that those etchings were from around the time of the pandemic, 1919-1920. Those etchings were used to illustrate A City of Caprice, a volume of poems about San Francisco written by Neill Compton Wilson, who was friends with Harold Ross, who would become the publisher of The New Yorker. Gormley speculates that it might have been these specific works that led to Shermund’s famous contributions to The New Yorker.

All the while, Gormley was working to amass as much of a collection of her aunt’s work as possible. In 2013, Gormley reached out to Liza Donnelly, the author of Funny Ladies: The New Yorker’s Greatest Women Cartoonists and their Cartoons and Michael Maslin, cartoonist for The New Yorker and author of Peter Arno: The Mad Mad World of The New Yorker’s Greatest Cartoonist. Donnelly would put Gormley in touch with an antique dealer on the Jersey Shore who had a large collection of her aunt’s work and personal effects. Gormley purchased many of those pieces, including letters from her grandfather to Barbara, and other letters that illuminated other fascinating aspects of her aunt’s life.

It was in that collection that she found checks and letters written to artist Ludwig Sander, who wrote Shermund throughout his time serving Allied powers during World War II. The last few of those letters to Shermund were written on gestapo letterhead following the Axis surrender on May 7, 1945.

It was around that time that Gormley felt that her research had truly become all-consuming, as well as incredibly expensive as she was purchasing as much of Shermund’s work as possible.

“I’m burnt out. I was talking about Barbara’s story and there’s so many layers to it that maybe five minutes into the story people were like, ‘Okay, Amanda. Yeah, that’s sounds cool.’ I was like, ‘I want to get her an exhibit. I want to write a blog. People don’t know about her,’” she said. “I kind of hit the wall. Then some health problems cropped up, and I retire from my investigative job and we pack up and move to Reno, Nevada.”

In Nevada, Gormley took a part-time job with United Airlines and utilized her flight benefits to do more research at public libraries in New York City. At that time, Gormley was aware that Shermund had maintained a business relationship with artist Eldon Dedini; whose son had donated a large portion of his father’s work to the Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon Museum in Columbus, OH. In 2017, Gormley contacted the Billy Ireland Museum and explained why she wanted to see Dedini’s work, and her massive research on Barbara Shermund. Gormley shortly made arrangements to travel out to Ohio to visit the museum’s archives.

“I went through the Billy Ireland archives and I was able to look at their collection and identify many aspects of what they had. It was really interesting because I was able to go in there and say, ‘This is that, this is that, this is that, this is that.’ And they were just like, ‘You’re kidding me!’” said Gormley.

Caitlin McGurk of the Billy Ireland Museum then explained that she was planning on researching Shermund and was hoping to interview Gormley as a part of that. Gormley filled McGurk in on the wealth of research that she had conducted on Shermund, and, eventually, gave some of her research materials to McGurk.

Together, McGurk and Gormley started a GoFundMe to fund the expensive process of properly laying Shermund to rest by her mother outside of San Francisco, which was massively successful. They raised over $7,000.

From there, McGurk organized the exhibition that is currently virtually on display at the Decorative Arts Center of Ohio.

“Caitlin was absolutely the right person at the right time — and with her passion and her own connection to Barbara, together we were able to move this. She was respectful of what I was looking for out of this,” said Gormley. “And really it was just to get Barbara her due.”

Now, the exhibition that McGurk curated is virtually on display. You can access the exhibition in the link embedded above, and you can listen to Gormley’s remarks about enduring appeal of Shermund’s work in the interview embedded above.