News

Larry Kramer, Pioneering AIDS Activist And Writer, Dies At 84

By: Neda Ulaby | NPR

Posted on:

Editor’s note: This story contains language that may be offensive.

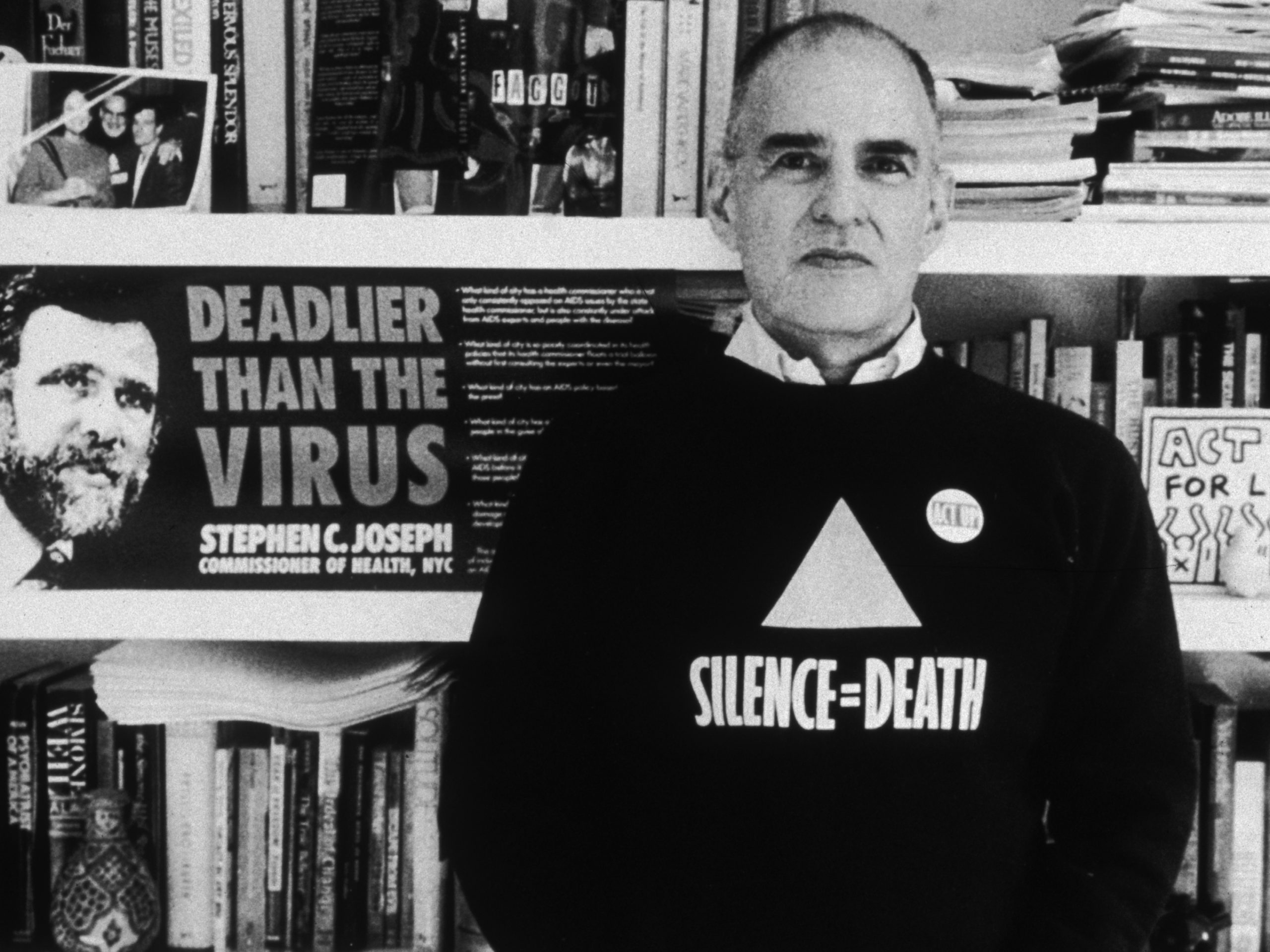

Larry Kramer was one of the first activists against AIDS, back when the disease didn’t even have a name. In the early 1980s, Kramer witnessed hundreds, then thousands of gay men die before the government took action to stop the spread of HIV. He became a high-profile, high-volume, one-man crusade against the disease.

Kramer died Wednesday morning of pneumonia in Manhattan, Will Schwalbe, his friend and literary executor, told NPR. He was 84.

Kramer was one of the great provocateurs of the late 20th century (and below you’ll see he wasn’t shy about using language that might shock or offend). In the 1990 documentary Positive, he told a group of gay men, “I am going to go out screaming so f****** rudely that you will hear this coarse, crude voice of mine in your nightmares! You are going to die, and you are going to die very, very soon unless you get up off your f****** tushies and fight back!”

Kramer wasn’t always what his friends called a “message queen.” In the 1970s, he was an up-and-coming writer with an Oscar-nominated screenplay for his film adaptation of the D.H. Lawrence novel Women in Love. In 1992, he told NPR’s Fresh Air, “I was in the film industry. I was on my way to making a great deal of money; I was not a gay man first by any manner of means until I became involved in fighting AIDS, and because someone close to me died. And suddenly I was no longer the white man from Yale, I was a faggot without a name.”

Faggots was the name of Kramer’s first novel, written a few years before AIDS destroyed his world. The controversial satire became a bestseller, although some bookstores — including a gay bookstore — refused to carry it.

Kramer had radical makings, even before the day in 1981 when he read a newspaper story about a new so-called gay cancer. He told Fresh Air, “My mind went back to incidences over the preceding couple years, where I had had friends who were mysteriously ill, lovers carrying their lovers around literally in their arms from doctor to doctor, from hospital to hospital, begging for ‘Have you heard of anything this could remotely resemble?’ ”

In 1982, with five friends, Kramer co-founded the Gay Men’s Health Crisis — for many years the largest provider of services to people with AIDS. Kramer became furious with the slow response of the medical establishment and the government as AIDS deaths skyrocketed.

In 1983, he published an essay taking gay men to task for what he saw as their shame and denial. “I am sick of closeted gays,” he wrote. “… Every gay man who was unable to come forward now and fight to save his own life is truly helping to kill the rest of us. … Unless we can generate, visibly, numbers, masses, we are going to die.”

The essay galvanized the gay community, but Kramer alienated his friends and allies. He took unpopular positions — railing, for example, against sex — and fought the organization he helped create. Kramer based his 1985 play, The Normal Heart, on his battle with the Gay Men’s Health Crisis. Even the character he based on himself was harsh and strident.

The Normal Heart was a hit. Critics praised its polemics and moral courage at a time when AIDS was barely discussed in the mainstream. But Kramer moved more to the extreme. He helped found a new organization, ACT UP.

“ACT UP was a direct action, educational and protest group, primarily,” longtime gay activist Urvashi Vaid said. The organization got attention for its in-your-face guerrilla tactics, but back then the group was also committed to serious research.

“People active in those research committees ended up being appointed by government officials in the ’90s to serve on [Food and Drug Administration] panels and advisory committees for the National Institutes of Health — they were that knowledgeable,” Vaid said.

ACT UP garnered national headlines with strategically outrageous tactics such as invading church services, outing public figures and embarrassing targets such as President Ronald Reagan, Cardinal John O’Connor of New York and New York City Mayor Ed Koch, who castigated Kramer at a 1989 press conference. “It’s very hard to deal with Mr. Kramer,” Koch complained. “No matter what you do, you’re going to be attacked and pilloried and smeared and slammed, no matter what you do!”

Kramer eventually fell out with ACT UP, too, and focused on his writing. He believed he was in a unique position to write an epic book about gay history. The American People: Volume 1 came out in 2015.

He told Fresh Air, “I was, for whatever reason, put on the front lines of the battlefield when the war started in 1981, and there are not many writers of us who are still alive. And I know where all the bodies are buried, both symbolically and literally.”

Kramer alluded to another writer, W.H. Auden, in a signature phrase: He insisted to friends and enemies alike — we must love one another or die.

9(MDI4ODU1ODA1MDE0ODA3MTMyMDY2MTJiNQ000))