News

The Missing Voters: The Ohio Valley Has Some Of The Nation’s Lowest Voter Turnout. What Could Change That?

By: Suhail Bhat | Sydney Boles | Alana Watson | Jeff Young | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

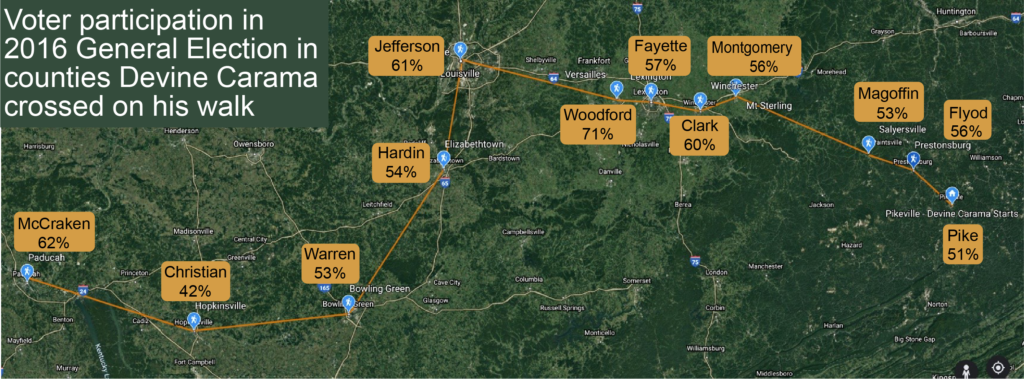

LEXINGTON, Ky. (OVR) — This fall, Lexington, Kentucky, activist and artist Devine Carama launched a different kind of road trip across his home state. He visited a dozen cities and towns, from Pikeville, in the state’s Appalachian east, to Paducah, near where the Ohio River joins the Mississippi. He carried a sign that said “I’ll walk 400 miles if you promise to vote.”

He wants to bring attention to what he says is the most important election of our lifetimes and to open up conversations about why people do or don’t vote.

“That was another kind of, you know, motivational piece to this,” he said. “How can we inspire people to not just register, but actually go out and vote?”

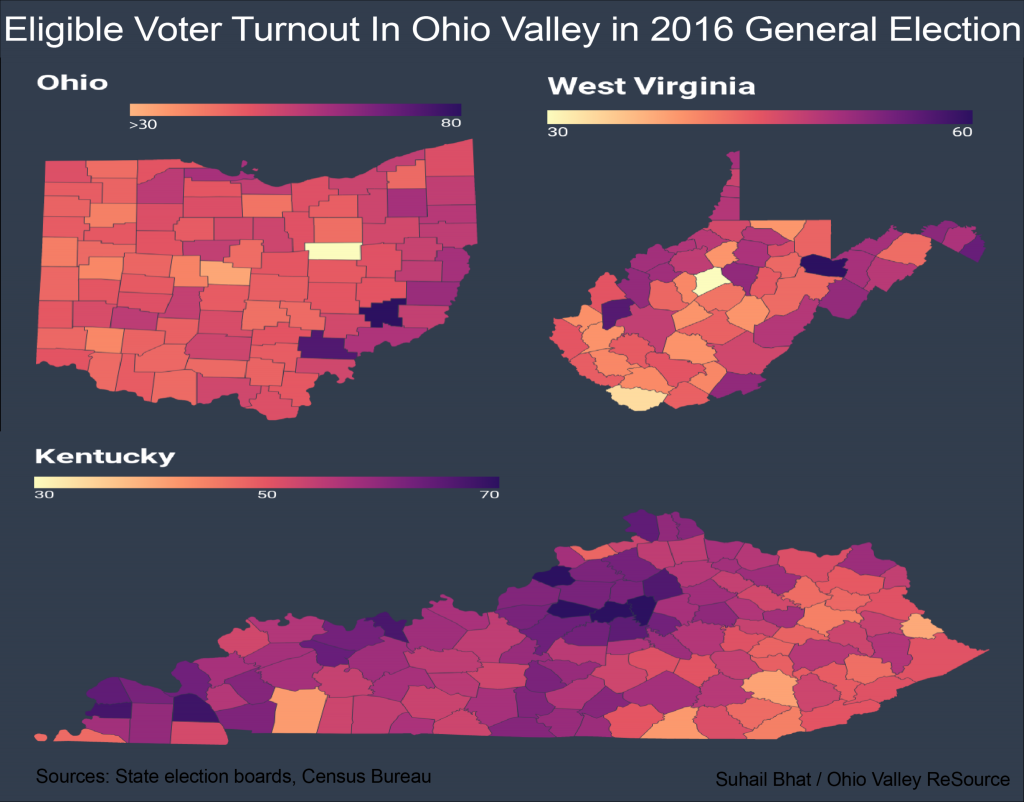

He’s got an uphill climb, and that’s not just because of the terrain. Portions of the Ohio Valley region — especially many of the Appalachian counties where Kentucky, Ohio, and the Virginias meet — include pockets of extremely low voter turnout, some among the lowest in the country.

“It’s healthy when we have high turnout,” West Virginia Wesleyan College political science professor Rob Rupp, a veteran observer of the region’s politics, said. “It’s dangerous to the civic culture when we don’t have a high turnout.”

If Rupp’s observation is true, the civic culture of much of the Ohio Valley is at risk from a combination of institutional barriers to voting and a deep sense of disconnection from politics, especially among lower- income residents.

The changes to voting rules in this extraordinary pandemic election year will likely boost voter turnout by greatly expanding options for voting by mail and at early, in-person polling places. But interviews with area residents and academic experts suggest that more than the mechanics of voting must change. Something else within American politics must change to motivate more voters.

By The Numbers

In the 2016 general election, voter participation increased slightly in Kentucky and West Virginia by more than 3 points each, but in Ohio voter turnout declined slightly by nearly one point.

Even after this gain, West Virginia had the second-lowest voter turnout in the nation, as 1 in 2 eligible voters participated in the presidential election. In Ohio and Kentucky, roughly 6 in 10 eligible voters voted. In the 263 Ohio Valley counties, more than half of the counties had voter turnout of less than 60%, while less than a dozen counties recorded more than 80% turnout. Half of the counties in West Virginia had a voter turnout of less than 40%.

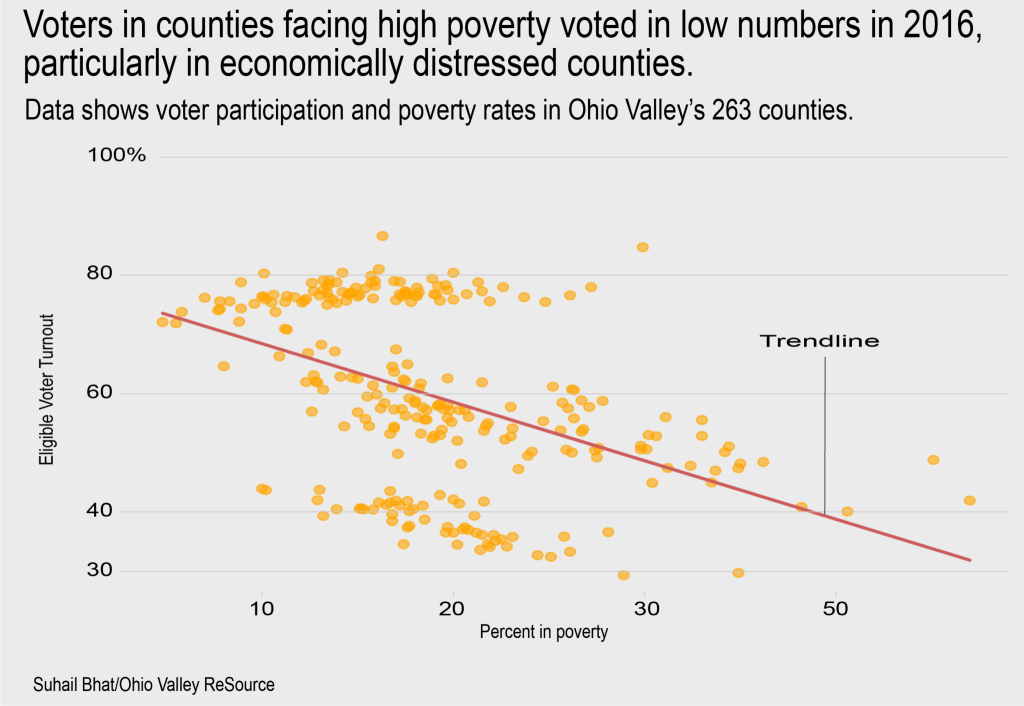

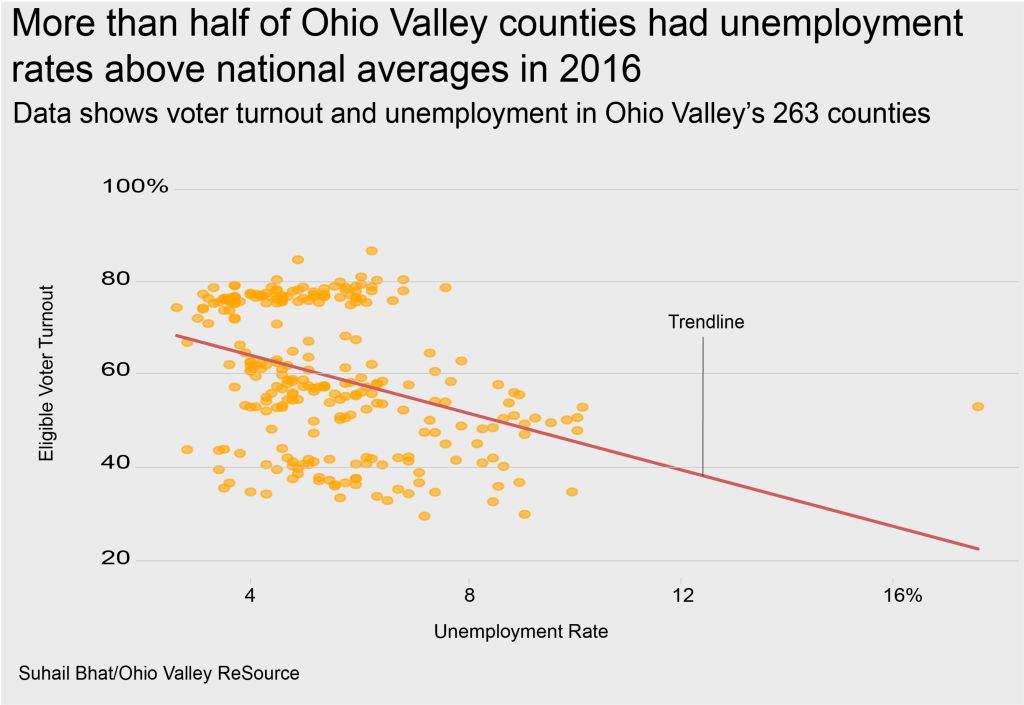

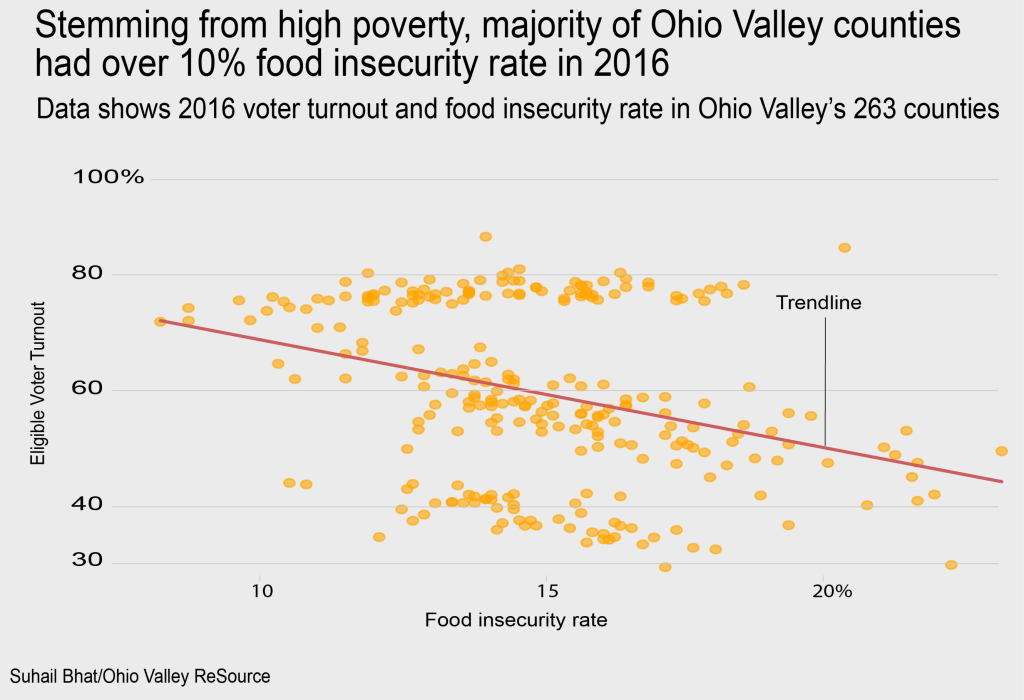

The ReSource analysis also compared voting participation in a county with socioeconomic indicators. Poverty rates in all three states were higher than the national average of about 12% in 2019. On top of that, these states were rocked by the opioid crisis that claimed thousands of lives and left hundreds of families without their primary earners.

Our analysis found that people in high poverty counties, who also face issues of food insecurity and high unemployment, vote in lower numbers, a sign that these voters don’t believe that an election is going to make a difference in their lives.

And as poverty increases, voter turnout decreases.

Counties in West Virginia such as Gilmer and McDowell had a depressing 30% voter turnout, which counts among the lowest in the nation. In economically distressed McDowell County, where Donald Trump bagged 75% of total votes, a third of the population lives in poverty while the unemployment rate is at nearly 10%.

Inequality v. The Vote

Derek Tyson and Missy Nestor are both life-long residents of West Virginia’s McDowell County, where they document daily life and events as the editor and publisher, respectively, of The Welch News.

McDowell, deep in the state’s southern coal mining region, started getting national media attention in the 2016 election as Donald Trump focused on the coal industry and miners as examples of a “forgotten” white working class.

But for Tyson and Nestor, the more important story isn’t the people who voted for Trump, but the larger majority who don’t vote at all.

“We ask this question a lot of people, ‘Why don’t you vote?’” Nestor said. “The main answer we get is, ‘Because it doesn’t matter.’”

Tyson joined in. “They feel McDowell County is going to be the same no matter what happens November 3.”

Per capita income hovers around $15,000 for McDowell Countians, and about a quarter of the people live with some kind of disability. Census estimates show the county lost about 20% of its population over the last decade.

“There’s a lot of hopelessness here,” Tyson said. “We’ve tried to combat it, but it’s even crept into our own hearts in some ways.”

The area was hit hard by the opioid crisis. “We feel we’ve lost a generation,” Nestor said. Much of this part of southern West Virginia is on the wrong side of the digital divide, with only about 60% of the county having access to broadband internet, which also makes it harder to get political information.

Tyson described elderly people making decisions about whether to fill needed prescriptions or pay utility bills. In that context, voting and national politics can seem remote.

“You get so caught up in just surviving, it’s almost like Maslow’s hierarchy,” he said, a reference to the psychology theory that people need the basics of life before considering more abstract issues. “If you’re trying to meet those basic needs, it’s hard to think on a national level.”

On top of that, Tyson and Nestor said, many people in their community feel burned by broken political promises and disrespected by the way they are depicted in national political media coverage.

“Everything in McDowell County has seemed an uphill battle for years and some people are just tired of fighting,” Tyson said.

Several studies have found that people with lower socioeconomic status are the least likely to vote in an election, and among those most likely to withdraw from political activity. Authors of a 2016 paper said people are “less likely to volunteer for a political campaign, contact a political official, attend a political meeting or wear a political campaign button,” when they are in low socioeconomic status.

“So, a political campaign’s first priority is not to get non-voters to vote. Their first priority is to win a campaign,” she said. That means little campaign messaging is directed to non-voters, who then get less information and fewer opportunities to register to vote or engage in political debate and discussion.

“We often blame people who don’t vote for being either selfish or lazy or uneducated,” she said.

“I think it’s important to emphasize it’s not just the characteristics of individuals who just don’t vote,” she said. “It’s who the political system is trying to mobilize and tell those citizens or provide an argument for why it’s important that they do vote, and I think that is a very big and important reason.”

The organizers of the Poor People’s Campaign recently published a report arguing that a political message that appealed to the interests of more low-income people could be a winning strategy. The Campaign includes religious leaders and social justice activists who are continuing the work of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who sought to connect economic and racial justice.

The report is titled “Unleashing the Power of Poor and Low-Income Americans.” The author, Rob Hartley, is an economist at Columbia University’s School of Social Work.

“What would it take for this group to matter in an election outcome?” Hartley asked. His report crunches the numbers on the proportion of low-income nonvoters in each state, then looks at what might happen if lots of them voted. Compared to the slim margin of difference in many states in the 2016 election, he found, such a mobilization of low-income voters could have changed the results in 15 states.

“If you were able to get low-income voters showing up at similar rates as higher income people, it could have changed the outcome,” Hartley said.

Hartley earned his doctorate degree at the University of Kentucky, and knows the region’s issues well. He said the report’s message is not about changing the outcome for a particular political candidate, but creating a path for a kind of politics that better addresses the needs of more Americans. And with the pandemic economy pushing more people into anxious circumstances, the timing could be right for a message about income support and health care access.

“The pandemic has certainly shown us that economic vulnerability could apply to anyone,” he said. “Just knowing how close any of us could be to poverty or hunger, not just those who are low income.”

Voting Barriers

One of the cities Devine Carama visited on his trek across Kentucky was Louisville, where 23-year old Marcus Morgan lives. Morgan was among those who responded to a question the ReSource posted online: If you’re not planning to vote, why?

A Democratic Socialist and a member of the LGBTQ community, Morgan is engaged in his community, occasionally attending Black Lives Matter protests and delivering groceries to homebound seniors. Morgan said he does vote, just not in the presidential election.

“I do very much believe in voting in the smaller elections, filling those seats, because those are the people we are going to be seeing running for president in our future,” he said in an interview. “But with the Electoral College and such it takes away the voices of many people.”

The winner-take-all nature of the Electoral College can serve to discourage voters in some heavily partisan states where the outcome of a race is not in question. Morgan says he knows which way deeply red Kentucky is going in the presidential race. (Gerrymandering of districts can have a similar effect in Congressional and state legislative races.)

The targeted nature of political campaigns can also alienate some voters, says Stephen Voss, an election and voting behavior specialist and associate professor of political science at the University of Kentucky. He says political campaigns are interested in people who are “safe bets.” That can leave “middle of the road” voters, as Voss says, feeling left out, even though they are the ones who can determine election outcomes.

Voss believes reducing the party polarization will result in healthier political engagement.

“To me the question of how do we stop what we see among the voters — the negativity, the voting against rather than voting for — is to figure out what’s allowed these parties to drift so far from the belief systems of most Americans and become so unified at ideologies that are unrepresentative of the people that might turn up on Election Day.”

“There’s a lot of money that gets spent on elections now, that is not spent by the candidates,” she said, leading to a sense that politicians are more responsive to monied special interests than to voter needs. “The negative impact is that people get turned off and decide not to participate.”

Stronger rules requiring transparency would at least give voters more information. (Full disclosure: Archer is a friend of ReSource Managing Editor Jeff Young.) Archer says basic changes such as automatic registration or same-day registration could also improve voter participation in her state.

Other voting rules in Ohio Valley states can serve to discourage or disenfranchise some voters. Ohio officials proposed a controversial purge of so-called “idle voters,” or people who had not voted in recent elections, from registration rolls. Critics say that creates an unfair hurdle for people to participate in voting and, further, the process could erroneously remove active voters as well.

Kentucky recently passed a voter identification law which critics say can discourage poor and minority voters. And until this year Kentucky was also among just a few states that banned people with felony records from voting, even after completing their sentences.

Even with Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear’s executive order this year restoring voting rights to many former felony offenders, about 1 in every 10 African Americans are still disenfranchised in Kentucky, well above the national average, according to a recent report by the voting advocacy group The Sentencing Project.

A Conversation

Despite the persistent pattern of low turnout in many parts of the region, election analysts expect voter participation to increase with this election, and they see some evidence of higher turnout recently.

Midterm elections typically have far lower turnout compared to presidential election years and, while that trend held true in 2018 participation increased considerably nationwide compared to the 2014 midterms. In the Ohio Valley, turnout increased by 14 points in Ohio, 10 in Kentucky, and 8 in West Virginia, an indicator of rising awareness and interest among the region’s voters.

And in a plot twist that could only come in 2020, the global pandemic that is forcing Americans to stay home has also paved the way for more voters to turn out. The threat of infection at a typical Election Day polling place forced officials in the region to adopt more flexible voting methods, such as early in-person voting and expanded options for mail-in and absentee ballots, which had not been options for most Ohio Valley residents.

That brought higher than usual turnout in the primary, despite concerns in Kentucky about the lower overall number of polling places on the day of the primary election. A record number of people have voted early as recent numbers show more than 70 million ballots cast nationwide and first-time voters turning up in large numbers.

By the time activist Devine Carama concluded his walk across Kentucky, he had travelled 401 miles. As he put it, it was the same as the number of years since the first enslaved Africans had been taken to a colonial America.

“She was very, I guess the kids today would call it woke. I know my daughter would have been on the front lines. My daughter was a huge advocate for protecting women, protecting black women, women’s rights. So I really kind of found an emotional connection to the Breonna Taylor situation, the tragedy of it all.”

On his second day on the road, Carama found himself walking through a place called Old Town, a coal town between Pikeville and Prestonsburg.

“Not a lot of people, not highly populated, but then also, there’s a huge racial divide in the eastern part of the state,” Carama said. “It leads to somebody like me, being an African American man, wearing a cloth backpack, you know, walking in the hollers of Eastern Kentucky is enough to give me a little anxiety.”

Rounding a bend in the road, Carama came upon a gas station and decided to stop in to charge his devices. All eyes were on him as he pushed through the glass door.

“One of them asked me, ‘So what are you doing out here?’” he said. “I showed him my sign, and I said, ‘Well, I’m trying to get people registered to vote.’ And he was like, “Well vote for who, because we don’t like outsiders coming around here telling us who we need to vote for.’

“But I was like, ‘Well this is actually a non-partisan walk that I’m going on across the state. I know who I’m voting for. But I’m not here to push that on anybody else. I just want you to use your voice, and vote regardless of who you vote for.’ And the change in his tone, his disposition, it was unbelievable how his defenses immediately dropped once he realized that I wasn’t there to promote a specific party. When I told him, I just wanted people to vote, it was like, immediately, he kind of stood down. And we were able to have a conversation.”

ReSource reporter Brittany Paterson and engagement specialist Tajah McQueen contributed to this story.

This story was produced in cooperation with America Amplified, a public media initiative funded by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. America Amplified uses community engagement to inform and strengthen local, regional and national journalism.