Communiqué

Discover The Architect of the Victorian Era in “PRINCE ALBERT: A VICTORIAN HERO REVEALED” – January 16 at 9 p.m.

< < Back toPRINCE ALBERT: A VICTORIAN HERO REVEALED

Saturday, January 16, 2021 at 9 p.m. on WOUB

Discover the Little-Known But Profound Role “The Architect of the Victorian Era” Played in Shaping Britain

Prince Albert is mostly remembered today as the beloved husband of Queen Victoria whose untimely death inspired decades of mourning. But a wealth of new material being released into the public domain suggests he played a profound role in shaping Victorian Britain. With remarkable access to Albert’s private papers and intimate family photographs currently housed in the Round Tower at Windsor Castle, author and historian Saul David examines Albert’s significant influence on British culture, government policy and even international relations. Initially viewed with suspicion and hostility by the British public and dismissed by Parliament, Albert faced an uphill struggle to carve out a leadership role. Such was his tenacity that by the time of his premature death at age 42, Albert was widely regarded as a forward-thinking reformer whose innovative ideas transformed the fortunes of the nation and created a legacy that lives on today.

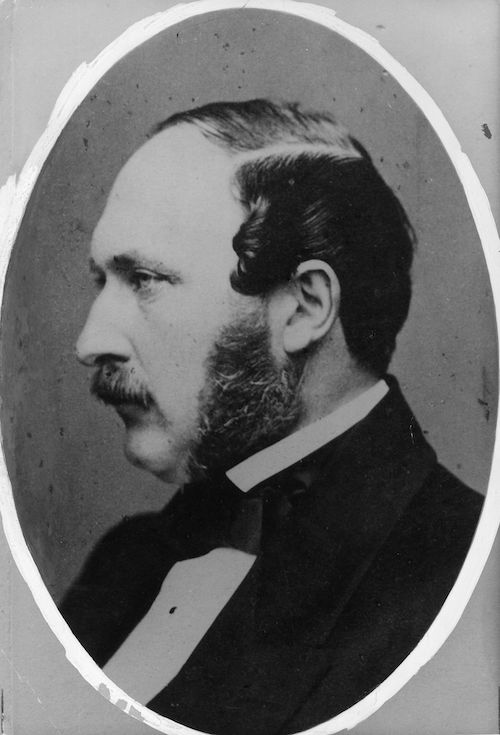

Born in 1819 in the small German principality of Coburg, Albert was promised from birth to his cousin Victoria — “the biggest career opportunity he will ever have,” says Daisy Goodwin, creator, writer and executive producer of the MASTERPIECE series Victoria on PBS. Luckily, Victoria was smitten from the first moment she saw Albert, known as the most handsome man in Europe, and they were wed in St. James Palace in February 1840.

Albert’s attitudes about marriage and family were profoundly shaped by the fact that his mother ran away with another man when he was five years old. Determined to be the ideal husband and father, Albert poured his heart into raising his nine children. Images from Photographs of Royal Children from 1855 to 1858 — shown for the first time on film — capture intimate moments of family life, including a photo of Queen Victoria holding an infant, surrounded by Albert and seven other children. The image, intended originally for private use, was the first photograph of a royal family allowed to be exhibited or published. Albert embraced the relatively new art of photography and understood that it could be used to enhance the royal family’s public image.

Albert became increasingly determined to create a public role for himself, one that would match his considerable abilities. Sneered at for being German and denied an active part in political life by Prime Minister Melbourne, Albert turned his attention to the royal household. Shocked at the levels of corruption and inefficiency, he began to prove himself by cutting the budgets. From 1842 to 1853, he saved an estimated 55,000 pounds per year, about 4.5 million pounds in today’s money.

With the savings, Albert began to modernize, undertaking ambitious architectural projects. His innovations can be seen in a dairy on the Windsor estate that is a model of form and function, and Osborne, a private residence for the Queen and family, the style of which was copied around the world.

Turmoil spread across Europe in 1848, and thousands of workers gathered in London to demand the right to vote. Albert understood that the world was changing and felt deeply about the plight of laborers and the poor. For the first time, he spoke out at a public meeting, saying that the ruling class could not exercise power without responsibility and must give something back. The following day, every newspaper published the Prince’s speech.

Albert’s campaign for change continued. He believed in education and that improving the quality of life for the working class would help resolve social problems. When he realized that the children of Osborne estate workers didn’t have a school of their own, he had one built. He encouraged wealthy benefactors to fund an early form of social housing by constructing model homes and publishing blueprints and budgets to help others build more. “By his own industry, he really invents the idea of the hard-working royal who justifies their existence by doing good,” says Goodwin. He had also become indispensable to Victoria, making decisions and managing her relationships with politicians.

In 1851, Albert embarked on his greatest gamble, the Great Exhibition, the world’s first trade fair with over 100,000 exhibits housed in a vast palace, the largest glass structure on Earth. Parliament predicted the Exhibition would fail and that London would be overwhelmed with crowds spreading disease and raising prices. But despite predictions of disaster, the Exhibition was a great success, attracting six million visitors.

In 1857, Queen Victoria changed her husband’s title to “Albert Prince Consort.” Albert was finally accepted by the British establishment, but the energy he had invested in making Britain a better place was taking its toll. In the winter of 1861, he fell desperately ill and died on December 14 with Victoria at his side. He was 42 years old. The Observer captured the nation’s grief: “England will not soon look upon his like again.”

Despite his short life, Albert left a remarkable legacy. With the 200,000-pound profit from the Great Exhibition, he bought a plot of land intending to create a cultural corridor. Today on that plot — London’s South Kensington — stands “the Albertopolis,” which includes the Victoria & Albert Hall, the Imperial College, the Royal Albert Hall, the Natural History Museum, the Science Museum, the Royal College of Music and more.

“I don’t think people do him justice because they don’t really understand what he did for us,” says Goodwin. “He was one of the great kings we never had.”