News

In elk, a Kentucky professor sees an opportunity to help revitalize Appalachia

By: Liam Niemeyer | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

MURRAY, Ky. (OVR) — Howard Whiteman is inching along in his black Toyota Prius, craning his neck to see what’s beyond the rolling grasslands into the nearby woods. He wishes he brought binoculars.

He’s slowly making his way around an enclosed 700-acre Elk and Bison Prairie in Land Between the Lakes National Recreation Area, the only public land in western Kentucky where one can see an elk and hear its distinctive bugle.

The elk were hard to find early that October morning, but that doesn’t surprise the sportsman.

“For such a large animal they can disappear so quickly,” he said. “Lots of other species are like that, but for such a large animal to do that, it’s pretty amazing.”

Whiteman grew up in southwestern Pennsylvania with reminders of how elk used to be treated differently in the region; he inherited from his grandfather an old book of game laws from the early 1900s when elk were reintroduced and hunted in the Keystone State.

But in Kentucky, the eastern subspecies of elk native to the state were gone by the end of the 19th century, overhunted and their habitat degraded as the coal industry increasingly made an impact on the land. It was more than a century later before efforts would solidify to bring them back to the state.

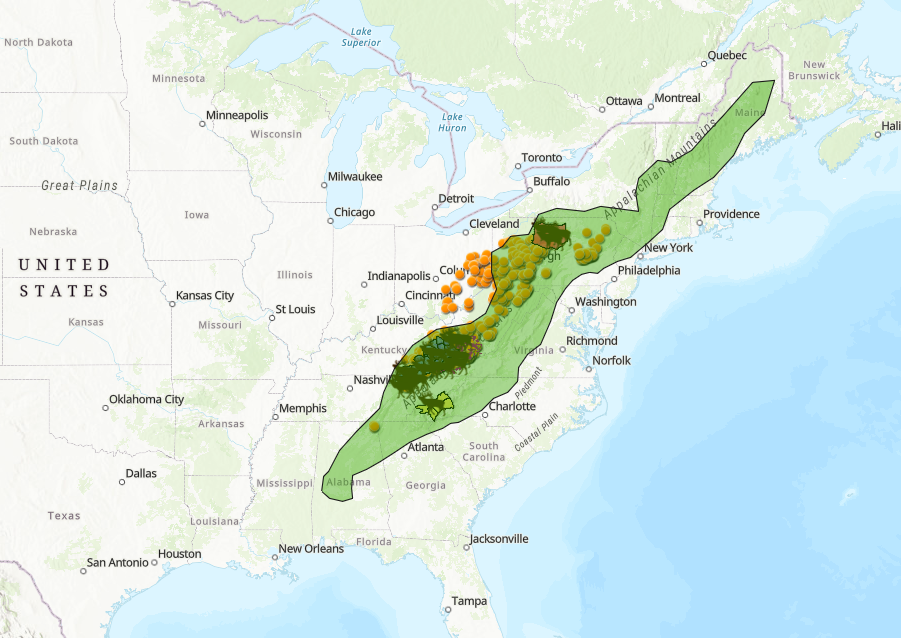

What started in 1997 as little more than 1,500 elk from the western U.S., released across eastern Kentucky, has become a conservation success story in the eyes of state wildlife officials: the largest elk herd east of the Mississippi River, with an estimated nearly 16,000 elk across 16 eastern Kentucky counties last year.

Whiteman got to see one of these large mammals up close during a hunting trip in 2014, winning a coveted hunting permit from the state. Seeing the hoof prints, seeing the bark rubbed off on trees by antlers, and hearing the bugles left an impression on him.

“If we restored some of these wild areas, not only for elk but just for people, we could create some sustainable forestry that would potentially drive that economy, or at least provide some of the jobs that for those coal mining jobs that just aren’t coming back,” Whiteman said.

He argues that creating such an expansive conservation corridor for elk could not only provide habitat for a myriad of species — songbirds, darters and mayflies, to name a few — but it could provide an economic boost to Appalachia through the hunting and tourism and the management of the conserved land. Across a region that has seen significant losses in coal production and employment, he believes the valued mammals could be a part of the region’s future.

Conservation advocates, biologists and wildlife officials who have been on the ground since the beginning of the eastern Kentucky elk restoration see potential in Whiteman’s idea with the benefits to biodiversity and species connectivity a corridor could provide. But the on-the-ground reality of working with local communities and the available resources could make the ambitious idea an upward climb.

Chris Garland, an eastern Kentucky native, remembers being fresh from graduating college and starting a job with the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources in the 1990s. Plans to move elk from western states, with help from the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, were already underway.

“I remember as a kid going to watch some of the whitetail deer releases that, people before me were doing and being amazed at that,” Garland said. “It was kind of surreal that we’re restoring a species here that hadn’t been here for hundreds of years was pretty amazing.”

Garland is now wildlife division director for the department, having also worked with Appalachian grouse and various wildlife management areas. He said he sees value in Whiteman’s idea for habitat connectivity, pointing to ongoing restorations of mussel species in Kentucky as an example. But there’s also the evident economic impact that elk bring.

“On average a Kentucky elk hunter last year and their helper — so, the people that went with him — on average spent almost $6,000 total on an elk hunt,” said Gabe Jenkins, who’s studied deer and elk as a biologist with the department for more than a decade.

Those expenditures include lodging, hunting outfitters, and taxidermy work that when multiplied by hundreds of elk hunters in the region each year can have a significant economic impact, Jenkins said. The department also brings in significant revenue from the tens of thousands of application fees for hunting permits the department receives each year for the chance to hunt elk.

Jenkins also said states such as West Virginia, Tennessee and Virginia have followed suit with their own elk herds. Jenkins sees the potential with an idea for an elk corridor given the existing herds across Appalachia, but he also sees challenges to implementing such an idea.

Jenkins said in eastern Kentucky, determining who owns the land to negotiate such an easement can be difficult, particularly with land associated with mining. He said sometimes parcels of land can have multiple heirs, or various entities can have different stakes in the mineral or timber rights of a property. Getting input from the larger community who sometimes use private lands for recreational use would also be important, he said.

“It’s not just as simple as the landowner and the lessee and the mineral [rights] and all that, but it’s also the people that are down the road,” Jenkins said. “We have to take all those voices into consideration and listen to them all. And it presents a challenge.”

Future uncertainty

For other conservation advocates, they see Whiteman’s idea aligned with a greater vision to protect land and biodiversity across the eastern United States. But available funding for such an expansive idea as a conservation corridor is only modest.

Dian Osbourne, the Director of Protection with the Nature Conservancy of Kentucky, said stakeholders involved in such a large, multi-state project would have to get creative with private landowners to develop such a corridor beyond outright buying the land. She said federal funding, like the Land and Water Conservation Fund, is absolutely necessary for helping fund conservation efforts across the country, but more resources would likely be needed. Whiteman has proposed, in part, that such federal infrastructure funding under consideration be directed toward conservation.

“There is a corridor that needs protection for that connectivity. You know, the ways to go about that? There are a lot probably a lot of different ways that you can slice and dice that,” Osbourne said. “And there are a lot of different partnerships that it’s probably going to take to make that connectivity work.

For one biologist who has been studying the eastern Kentucky elk since their reintroduction, he wonders what the long-term impacts an expansion of elk across Appalachia could have. John Cox with the University of Kentucky sees the ecological damage that dense deer populations have had in some eastern states, overeating and impacting plants, including ginseng in West Virginia.

“[Deer] are altering the trajectory of the forests in terms of the species that are surviving and able to grow up into mature trees,” Cox said. “When do you cross the threshold where the impact becomes a concern, from an ecological standpoint, that this is doing damage? And that could be hard to tease out.”

Regardless, Cox hopes that as eastern Kentucky and other parts of Appalachia determine how to best use their land as the region transitions away from coal that community stakeholders are involved in the discussion.

“What’s going to be there for people economically 20, 30, 40 years from now?” Cox said. “Tourism and forestry seem to be the more sustainable and compatible natural resource practices for central Appalachia.”