News

Inconsistent laws and tracking systems make it difficult to count intimate partner violence deaths in the Ohio Valley

By: Corinne Boyer | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

Teresa Wilson’s first apartment of her own was a big deal.

Thomas understands the intricacies of intimate partner violence — especially when addiction is involved. She’s a team coordinator at the West Virginia Coalition Against Domestic Violence.

“They are less likely to reach out for help, they can be vulnerable, just physically and cognitively, right, when they are intoxicated or high,” Thomas said. “They often times use drugs and alcohol to ease the pain, to ease the abuse, to self-medicate.

The situation for Wilson grew worse. Her partner ultimately killed her.

“Me and my niece couldn’t save my sister. It wasn’t for the lack of trying, and we still would be trying to this very day if she was still alive,” Thomas said.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention consider intimate partner violence, or IPV, a “serious public health problem.” During the COVID-19 pandemic, IPV deaths have increased both in West Virginia and Ohio. Data isn’t available yet for Kentucky.

Some nonprofits that track IPV homicides use news reports, but not every death is reported on. Advocates are working to gain more access to usable data and to close loopholes in laws meant to protect survivors.

West Virginia

In West Virginia, state law says that a fatality review team must present suspected IPV death data to the legislature every year.

Joyce Yedlosky, a team coordinator at the West Virginia Coalition Against Domestic Violence, said her organization doesn’t currently have access to that report. Now they’re working on changing that.

“We want to be named to be somebody who has access to that report,” Yedlosky said. “We have a domestic violence prevention effort to try to reduce domestic violence homicides, and it would be great to have that report to help guide us to see if our efforts are effective.”

Yedlosky said the organization last received the West Virginia Domestic Violence Fatality Review Panel Annual Report in 2014. That report found that 75 deaths were linked to domestic violence.

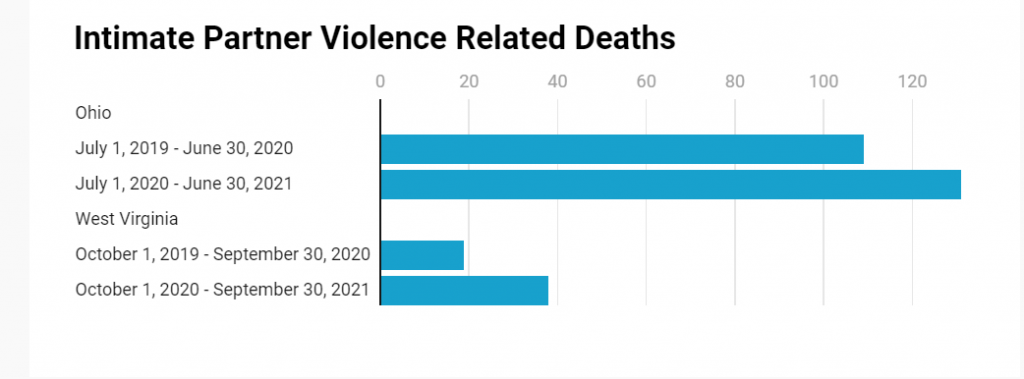

The count is significantly higher than the report Thomas puts together using media reports. From Oct. 1, 2019 through Sept. 30, 2020, 19 deaths were reported by the West Virginia Coalition Against Domestic Violence. During the same time frame the following year, deaths doubled to 38. Thomas said the count is likely underestimated, but she isn’t able to compare it to official state data.

“I’m sure that there were more than 38 domestic violence-related deaths last year,” Thomas said. “I’m sure, it’s probably double or triple that number, but I just don’t have access to that data.”

One name included in the coalition’s 2019 report was Trinity McCallister. She was 35 at the time of her death. She was a mother of four. McCallister’s partner killed her.

Kimmy Frost was McCallister’s best friend. They met in third grade and stayed close through middle school and high school, when McCallister had her first child.

When Frost became a mom, too, her children knew McCallister.

Frost said it’s still extremely difficult to talk about her best friend.

“My daughter actually went with me to Trinity’s funeral. [My kids] they actually knew her and they just knew that it was really hard on me. She was like the friend that I had the longest. The person that I was the closest to growing up.”

Ohio

Mary O’Doherty is the executive director of the Ohio Domestic Violence Network. Her organization also uses media reports to track deaths. Data shows that IPV-related homicides increased by 20% from July 1, 2020 through June 30, 2021 compared to the year before. That’s an increase of more than 62% compared to data from two years ago.

“The thing that was, I think, very sad about the report was that 15 young victims were killed. And that was the largest annual number of minors to die since we began counting.”

The Ohio Domestic Violence Network published its first report in 2015.

“The fact that so many of the perpetrators had been engaged with the criminal justice system before the homicides happened is really significant,” O’Doherty said. “And it just underscores, I think, how prevalent domestic violence is, what a big issue it is for our criminal justice system and how we have so much work to do.”

Kentucky

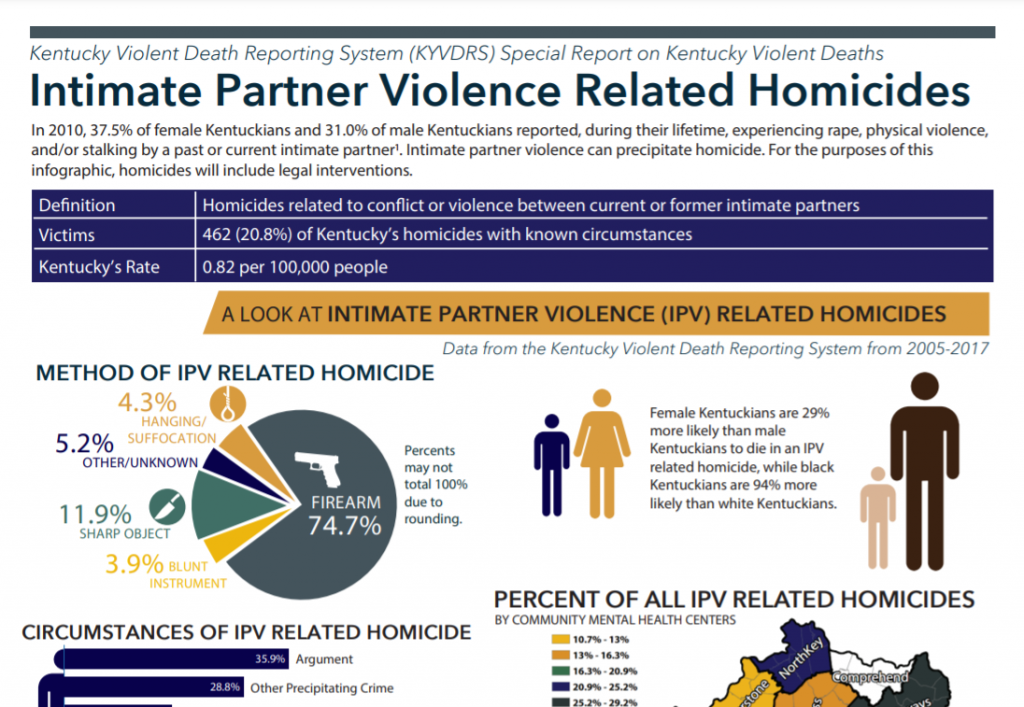

The University of Kentucky maintains statewide data on IPV deaths called the Kentucky Violent Death Reporting System. Data comes from multiple sources including coroner, police, toxicology and crime scene reports. Sabrina Brown, an associate professor at the UK College of Public Health, runs the program.

“All we have is the information that’s given to us from the investigators,” Brown said. “Another limitation is a family member might not want to disclose that there was intimate partner violence. Or a friend, they might hide it from the investigator.”

The system collects data statewide, but Kentucky isn’t required to keep track of IPV deaths. If a domestic violence services agency needs data from the system, Brown said it’s available with a request form.

“We can provide, and we’re happy to reply, provide data, request information to any entity, especially advocates, because they need the evidence base to support their activity.”

Although KYVDRS death reporting lags by a few years, data for 2020 won’t be available until this summer, one statistic is staggering. More than a decade’s worth of data estimates that Black Kentuckians — male and female — are 94% more likely than white Kentuckians to die in IPV-related homicide.

“And that is often because the intervention point may be later,” Hunt said. “So some of those communities, Black women in particular, may be more hesitant to reach out to services or to report to police, because of historical barriers, because of perceptions of safety or whether or not they will be able to receive services that meet their needs.”

Darlene Thomas is the executive director of Greenhouse 17, a domestic violence services organization and shelter in Fayette County. Thomas said Kentucky does a good job at tracking domestic violence-related crimes.

“Kentucky has done an excellent job at standardizing other forms of tracking, like the protective orders, and police officers across the state have access to a protective order immediately,” she said.

Hunter Hickman, a lawyer with The Nest Center for Women, Children and Families in Lexington, said clients often ask what good a protective order will do.

“They do work and oftentimes they are not violated because of their deterrent potential and the fact that they do deter people from reaching out because you know, people do not want to go to jail,” Hickman said.

Violating a protective order is a misdemeanor, and that could mean spending a up to a year in jail. Hickman said repeat violators may be deterred, for example, if they faced a felony charge.

“And so then you’re talking about one to five years in prison, so maybe some change like that would be beneficial for those people that are kind of just persistent repeat violators,” he said.

Darlene Thomas said data alone won’t solve the problem. But it’s something that needs attention.

“But without it, we’re not going to be able to intervene, understand and reduce those numbers,” she said. “And so the rates of death don’t move, and it just feels like we’re not valuing the experience of domestic violence survivors.”