News

Displaced Kentuckians are still searching for housing after tornadoes

By: Liam Niemeyer | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

MAYFIELD, Ky. (OVR) — Jimmy Galbreath works hard. The scrap dealer and father of nine from Mayfield, Ky. started working when he was 12 years old. He grew up in a one-bedroom house with 15 other siblings and a mother who made sure they had food on the table. And eventually, he worked hard enough to build a life for himself on South 5th Street in Mayfield, where he bought a home for $2,500. The church next door sold him another house on the street for a dollar.

“If you want that house, right? You got to work for it,” Galbreath said. “Ain’t nobody going to give you that stuff.”

But on a chilly morning in February, Galbreath watched an excavator claw tear one of the homes into rubble. Both homes were damaged beyond repair by a violent EF-4 tornado on Dec. 10, part of a catastrophic tornado outbreak that ripped through the Kentucky town of 10,000 and transformed the lives of thousands more across the region. Community members have lost loved ones, historic buildings and a direction for the future.

But for Galbreath, it wasn’t a moment of loss; it was a new start.

“I know that I got a home coming where I’ll be warm and cool in the summertime,” he said. “I’m grateful, and thanks to the man upstairs,” Galbreath said.

Not all tornado survivors have been as fortunate.

More than two months after the tornado outbreak tore through western Kentucky communities, hundreds of those displaced by the natural disaster are still living in hotels, state lodges or homes still in need of repairs. Some survivors like Galbreath see hope on the horizon and are willing to wait in a hotel for the near future. But others are facing the uncertain reality of a housing shortage that existed before the storm, and it could mean the difference between whether someone chooses to stay or leave their community.

What Gets Rebuilt

Greg Vaughn helped maintain public housing units for almost two decades before he became the executive director of the Mayfield Housing Authority in 2020. In the short time since he took up the post, he’s had to deal with two historic events that disrupted the lives of his residents and community: the coronavirus pandemic and a tornado that destroyed much of his city’s housing stock.

In the weeks after the tornado, he says he overheard someone talking about how the tornado only hit low-income housing in Mayfield – “just shacks,” as he heard it.

“It kind of upset me. It’s people’s homes is what it hit,” Vaughn said. “It don’t matter what it is. It’s their home.”

“When we get warmer temperatures, that mold is really gonna take off,” Vaughn said.

As he drives around in his truck, he sees the other low-income housing that may not be rebuilt in Mayfield. He points out the window to the destroyed Eloise Fuller Apartments near downtown, where many lived in subsidized rental units through the Section 8 program.

Vaughn estimates about 60% to 70% of Mayfield consists of rental properties, and it was an impoverished community before the storm: the poverty rate was three times the national average at approximately 34%, according to U.S. Census data. He said many landlords may choose to not rebuild.

“It’s not worth it to them,” Vaughn said. “Especially for the cost of materials, what it costs for them to rebuild them houses now, they’re just, it’s not profitable to do that.”

Between people who lived in public housing or used the Section 8 program before the tornado, Vaughn said there are about 100 low-income Mayfield residents who are still displaced. He knows some have already decided to leave Mayfield for nearby Kentucky communities like Fulton and Paducah.

Housing advocates say the thousands of destroyed or damaged homes from the tornado outbreak only exacerbated the affordable housing shortage across the region.

Not Enough Homes

Danny Fugate is a leasing navigator for the Kentucky Homeless and Housing Coalition in western Kentucky and saw a need for affordable housing in his area long before the tornadoes, but the situation has gotten worse. Waiting lists at housing authorities in Mayfield and nearby Paducah can reach into the hundreds, and rental prices are increasingly unaffordable.

“We don’t have that middle ground in terms of affordable housing to low-income households,” Fugate said. “We’re trending toward anywhere from $750-up for a one-bedroom apartment [in Paducah].”

Fugate’s job is to secure rental homes for low-income people in far western Kentucky, including a Marshall County mother who was living in a tent that was destroyed by the tornado.

Fugate said the destruction has only compounded the lack of housing, especially rental and assisted living housing.

“You’ve placed a sizable number of folks into the rental market that was not previously in the market, along with the renters whose rental property was destroyed,” he said. “It makes it a tighter market for the folks that we’re trying to locate housing for.”

According to the National Low-Income Housing Coalition, Kentucky already lacked 77,701 affordable and available rental units for extremely low-income renters before the storm, with 62% of renters facing a “severe cost burden” – meaning their housing expenses crowded out other necessities.

“There are all kinds of things that the federal government and state government does direct spending on that we consider a basic human right, like education,” Bush said. “We need to really think about how do we create more housing to address the shortage of physical homes.”

Bush points to parts of President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better Act that would provide hundreds of millions of dollars in funding for low-income rental housing as a place to start that investment.

But in Kentucky, there’s a more immediate challenge of how to temporarily house people whose homes were destroyed by the December tornadoes.

More than two months after the disaster, the Federal Emergency Management Agency has not started moving displaced people into temporary housing like camping trailers or manufactured homes. According to a statement, the agency is still moving through the “long process” to lease existing homes in the region. State officials are trying to provide approximately 200 travel trailers to displaced Kentuckians, but have only given them out to 18 families as of Feb. 9.

Gov. Andy Beshear recently said some displaced people have found housing on their own or moved in with family instead of seeking out the trailers. He said about 66 people are still waiting to receive trailers within the next month.

But, Beshear said, some displaced people are going to have “tough conversations.”

“At some point that hotel or motel is gonna need their rooms back,” Beshear said. “We’re gonna have some people that we’re gonna have to say, ‘we have two or three windows to repair and that’s it. It’s time to get it repaired to move forward.’”

Thomas Chandler, deputy director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University, said FEMA has been successful in getting natural disaster survivors into hotels and motels to serve as immediate housing, but has challenges finding more permanent solutions beyond those hotels and motels for people.

“That is becoming more and more challenging as we’re seeing more disasters and a changing climate, particularly in rural areas,” Chandler said. “The challenge is what comes after that.”

He said FEMA’s bureaucracy has a hard time providing temporary housing units. The agency sometimes takes months to connect people with places to live after a disaster. So far, the vast majority of Kentuckians that have applied for FEMA aid have been denied. More than 4,300 were considered ineligible for housing assistance from FEMA because they couldn’t be contacted or missed an inspection.

Those challenges don’t lessen the anxiety and uncertainty faced by survivors.

Struggling With Where To Go

For Felicia Murrell, the uncertainty of waiting has been nearly unbearable. The 38 year-old and three of her children have been staying in a room at the Kentucky Dam Village State Resort Park since the days after the tornado, one of more than 250 displaced Kentucky individuals still staying in state park lodging following the storm.

The Mayfield mother said Red Cross representatives have been calling her to ask about her moving out plans and giving her a deadline toward the end of the month. The roof of her public housing unit in Mayfield fell through, she said, though a Red Cross representative told her the home only sustained minor damage. She doesn’t yet know where she’ll go. She said the stress of the calls has compounded the trauma she’s already been dealing with.

“Our town has been tore apart. And it ain’t even been two months and y’all are trying to get up and into another house,” Murrell said.

She said she and her son are both getting therapy and that she’s been scared her kids would be removed from the lodge while she’s away at work.

“When I’m not around my kids, I cry. It’s awful,” Murrell said.

Murrell said she doesn’t want to go back to the public housing unit her family was living in because of the terrifying memories it evokes. She remembers watching the tornado come from her backdoor.

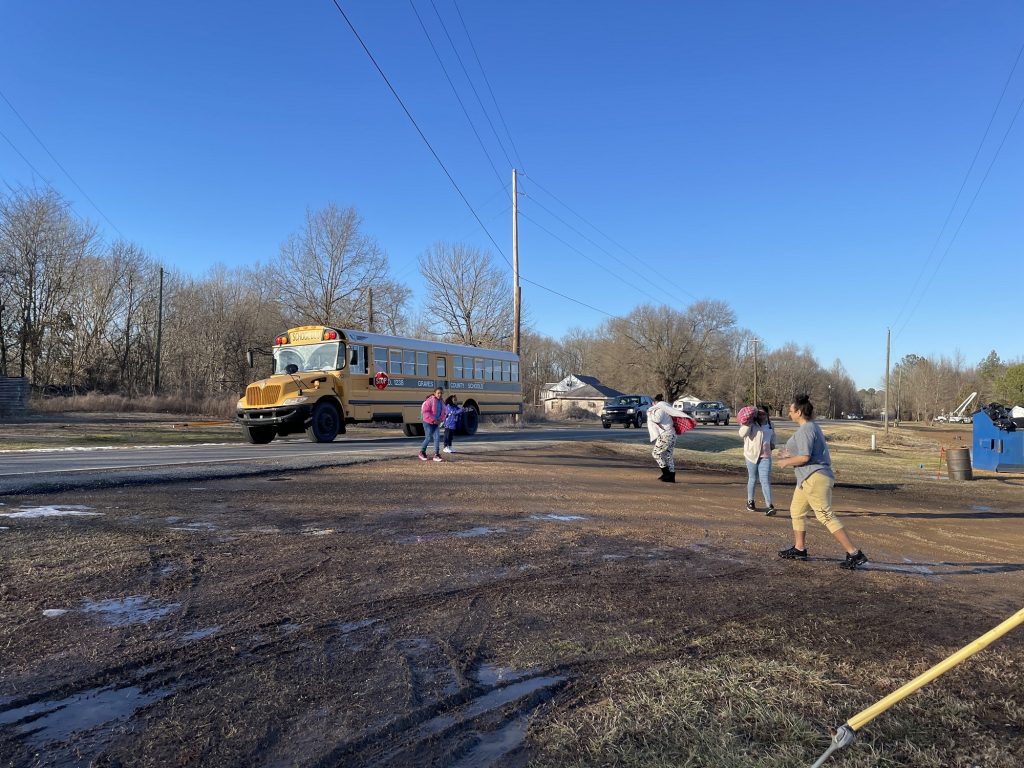

“I’m a prime example of ‘don’t want to leave but should leave,’” Murrell said. “I don’t want to leave because my kids are comfortable where they headed to school. They love their school, they got their friends.”

A Kentucky State Parks spokesperson didn’t answer a question about whether those displaced in state parks had been given timelines or deadlines to move out. The Red Cross didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

Murrell applied to move into a “tiny home” built by local churches trying to keep community members in Graves County and Mayfield, though she hasn’t yet heard back.

About 10 miles south of Mayfield, Micah Seavers has been helping deliver food and heating fuel to tornado survivors throughout the region, especially as temperatures recently dipped below freezing. Seavers owns Southern Red’s BBQ & Catering in Pilot Oak and has been trying to provide shelter for some displaced people by building tiny homes on his property.

“If I want to help people, I’m gonna help people. Nobody’s gonna say, ‘oh, well, you can only help them this way or that way.’ No, we’re just gonna help them. That’s what we’re gonna do,” Seavers said.

Mayfield and Graves County struggled before the tornado and Seavers says the disaster “opened a lot of people’s eyes” to the disparities of the region. He said he wants to use the tiny homes as a place for families to seek education like GEDs and learn practical skills like finance or cooking classes.

As his daughter helps him mark out the planned construction area with little orange flags, Seavers says he wants to keep his community intact.

“These people who are discouraged now are just going to leave,” Seavers said. “I feel like we just need to push, and I hope that this is something that can help with that.”