News

Online pricing algorithms are gaming the system, and could mean you pay more

By: Ziad Buchh | NPR

Posted on:

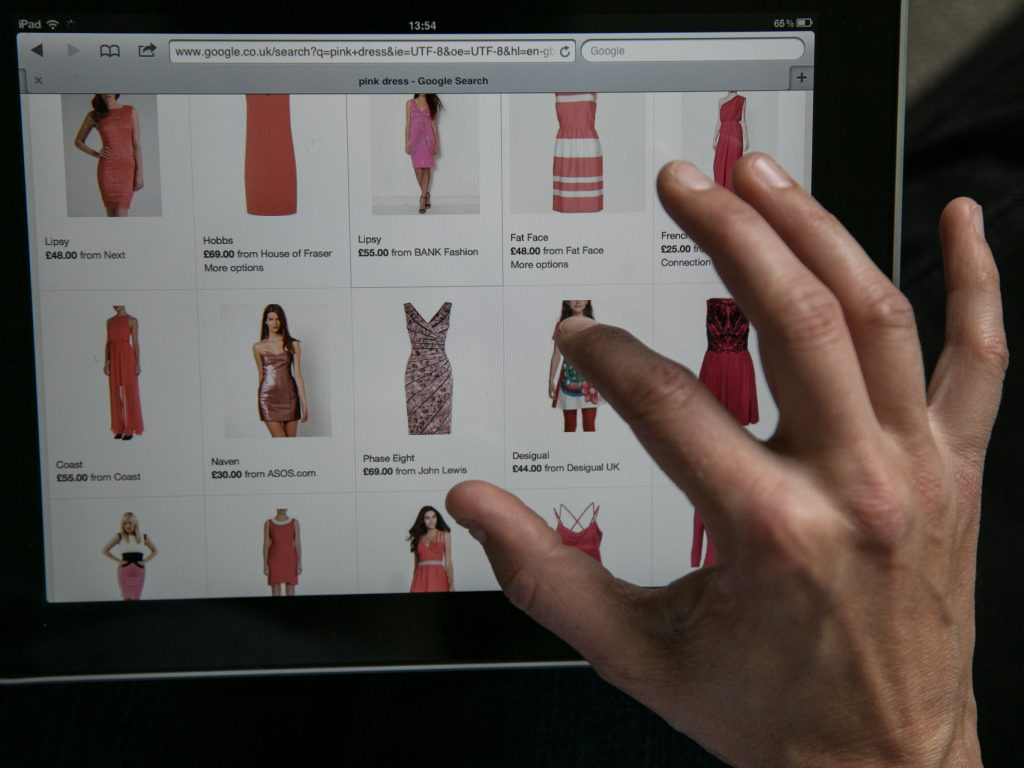

WASHINGTON, D.C. (NPR) — If you’ve shopped online recently, you may have had this experience: You find an item, add it to your cart, and then when you get around to paying, the price has increased.

You can thank pricing algorithms.

These are computer programs that look at factors such as supply, demand and the prices competitors are charging, and then adjust the price in real time. Now, there are calls for greater regulation at a time when these tactics are expected to become more common.

“A key thing about the algorithm is that given different inputs, like, say, time of day or weather or how many customers might be showing up, it might decide on a different price,” said Harvard economics professor Alexander MacKay.

Theoretically, these algorithms could be good for competition. For example, if one business sets a price, the algorithm could automatically undercut it, resulting in a lower price for the consumer.

But it doesn’t quite work that way, MacKay said. In a paper he co-authored in the National Bureau of Economic Research, he studied the way algorithms compete. He found that when multiple businesses used pricing algorithms, both knew that decreasing their price would cause their rival to decrease their price, which could set off a never-ending chain of price decreases.

This, MacKay said, takes price competition off the table.

“Why try to start a price war against a firm whose algorithm will see my price change and immediately undercut it,” he said.

The impact of algorithms can be more than just a few extra dollars at checkout. During the 2017 terrorist attack on the London Bridge, Uber’s pricing algorithm sensed the increased demand and the price of a ride surged in the area. Uber later manually halted surge pricing and refunded users.

A study published in the Frontiers in Psychology journal found that price discrimination led to decreased feelings of fairness and resulted in “disastrous consequences both for the vulnerable party and for the performance of the business relationship as a whole.”

It’s a point echoed by professors Marco Bertini and Oded Koenigsberg in the Harvard Business Review. They wrote that pricing algorithms lacked “the empathy required to anticipate and understand the behavioral and psychological effects that price changes have on customers,” and that, “By emphasizing only supply-and-demand fluctuations in real time, the algorithm runs counter to marketing teams’ aims for longer-term relationships and loyalty.”

MacKay said a few regulations could help avoid some of these consequences and bring competition to a more standard model. The first would be preventing algorithms from factoring in the price of competitors, which he said was the key factor weakening price competition. The second was decreasing how frequently businesses could update their prices, which he said would mitigate or prevent a business from undercutting a competitor’s price.

Yet ultimately, MacKay said pricing algorithms were only going to get more common.

“Firms are trying to maximize profits and they’re trying to do it in a way that’s legal and competitive,” he said. “It’s sort of in your best interest to adopt an algorithm to be able to consistently undercut your rivals to maintain a market share advantage.”

9(MDU1ODUxOTA3MDE2MDQwNjY2NjEyM2Q3ZA000))

Transcript :

LEILA FADEL, HOST:

You know when you’re trying to buy something online – you might put an item in your cart, then do some more browsing. And maybe you’re deciding whether you really want it or you just want to shop around a bit more. But sometimes when you get back to your shopping cart, the price is suddenly higher. The reason could be the pricing algorithms many online retailers are using to adjust their prices without another human entering a single keystroke. Our co-host Steve Inskeep asked Harvard economics professor Alexander MacKay what’s going on and what it all means for consumers.

ALEXANDER MACKAY: A pricing algorithm is simply a step-by-step set of instructions. And these instructions can be very simple, or they can be very complicated depending on the algorithm that a company chooses to do. But a key thing about the algorithm is that given different inputs – like, say, time of day or weather or how many customers – it might decide on a different price. And one of the things that’s particularly interesting and a focus of our research is that a lot of companies use algorithms that depend on the price of their competitors.

STEVE INSKEEP, HOST:

I guess some people are very familiar with this if they travel very often because they know that airline seat prices change constantly. They can change in the space of five minutes. Is this the kind of thing we’re talking about?

MACKAY: Yeah, that’s exactly right. So airlines have been using pricing systems that allow for time-varying pricing for a long time. One thing that’s sort of changed in recent years is that a lot more retailers have been adopting high-frequency pricing algorithms, you know, in particular in online markets. So one thing that I think a lot of people expected with the rise of online markets was that there’d be very intense price competition, and you’d sort of see the same prices on every different website, in part because it’s pretty easy to shop across online retailers – right? – just a few clicks to go from one website to another.

But in fact, that hasn’t actually happened. There are big price differences across websites, which is sort of surprising. In fact, I just checked this morning. You know, I’m looking at a 15-pack of Allegra tablets, which is a common allergy drug. And on Amazon, it’s showing me a price of 12.99; at Target, it’s showing me a price of 15.69; and at Walgreens, it’s showing me a price of 17.99. We’re looking at a $5 price difference for the exact same product.

INSKEEP: What’s going on there? Are they all running their own algorithm?

MACKAY: Yeah. Some retailers have much more high-frequency pricing algorithms that allow them to update their prices, you know, say, every 15 minutes. The other thing we noticed was that the firms with the faster pricing algorithms consistently priced lower than their rivals. The question is, is this a good thing? When you actually get into the economics of it, what it can do is actually discourage price competition among retailers. But if you have sort of a slower technology and you know that one of these faster firms is always going to undercut whatever price change you make, it sort of takes price competition off the table. So why try to start a price war against a firm whose algorithm will see my price change and immediately undercut it within the span of 15 minutes potentially? I don’t really have much of an opportunity to gain market share.

INSKEEP: Although I guess that points to another reality about these algorithms. They are not necessarily set up for the benefit of customers. They are set up for the best interest of the person who’s paying for the algorithm.

MACKAY: Absolutely. Absolutely. So firms are trying to maximize profits, and they’re trying to do it in a way that’s, you know, legal and competitive. If you’re a company and you’re trying to decide, should I adopt this algorithm or not? – it’s sort of in your best interest to adopt an algorithm to be able to consistently undercut your rivals, to maintain a market share advantage, but also to have this secondary effect of discouraging them from competing with you on price.

INSKEEP: Wait a minute. So I’m going to offer the lowest price, but I’m not going to have a race to the bottom because nobody else is going to try to get below me.

MACKAY: That’s exactly right. So even though, relatively, it looks like the faster firm has the best price and is being competitive, because I’ve taken price competition off the table, my price can even be higher than it would have been otherwise.

INSKEEP: This sounds like yet another way that the internet feels free, but it’s not free at all to the consumer.

MACKAY: I think it’s certainly counterintuitive, and it has some features that look a lot like intense competition. But absolutely, when you get into it a little bit, seems to have these effects that are a little bit surprising.

INSKEEP: What would you do about this as a government matter, a policy matter or as an ordinary consumer?

MACKAY: So one feature that these algorithms have is that they respond to the price changes of rivals. So if regulators are somehow able to limit or prevent companies from directly incorporating rivals’ prices into the algorithms, that might be one way to sort of take away the threat of undercutting their price and actually drive prices down across the board. So, again, a big reason why firms might be disincentivized from lowering their price is that your rival company’s going to quickly respond with another price cut. But if we, say, regulated companies to change prices only once a week or once per day, you know, in certain markets, that would prevent a company from threatening to quickly undercut their rivals’ price changes.

INSKEEP: I’m wondering if these algorithms have been significant enough in their effects to be a factor in inflation. You’re in this marketplace that ought to drive prices down, but instead they sort of drift upward or stay in place.

MACKAY: Algorithms could absolutely have an effect on inflation. They are able to more quickly respond to changes in various factors in the market, both in terms of demand – what consumers are wanting – and also in terms of supply, in terms of input cost. Some traditional pricing practices consist of manufacturers sort of deciding once per year what their prices are going to be. And in those settings, you sort of have to anticipate what’s going to happen over the course of the year. And you may not be able to respond quickly to supply chains disruptions that we’ve seen. And so I think under traditional pricing, certainly, we might have seen slower price increases than what we see today with pricing technology that can really take into account changes in the market in much more timely basis.

INSKEEP: Alexander MacKay is a Harvard economics professor. Thanks so much.

MACKAY: Thank you so much.

(SOUNDBITE OF LUSINE’S “PANORAMIC”) Transcript provided by NPR, Copyright NPR.