Culture

Author David Contosta headed to Lancaster Oct. 16 to talk about ‘American Childhood’ in the ’50s

By: Emily Votaw

Posted on:

LANCASTER, Ohio (WOUB) – David Contosta and Phillip Hazelton are cousins. They grew up in a tight knit family. The kind that got together every Thanksgiving for a dinner in the same house for decades.

On one of those Thanksgivings, Contosta and Hazelton got to talking about their childhoods: American childhoods set in the near Midwest in the near mid-century. Once they got to talking, it wasn’t easy to stop. Once the conversation had outlasted Thanksgiving Day they took to exchanging their recollections via letters and email. Out of that correspondence grew the idea of collecting these stories in a book, one that could be shared with family members first, and then perhaps a larger audience after that.

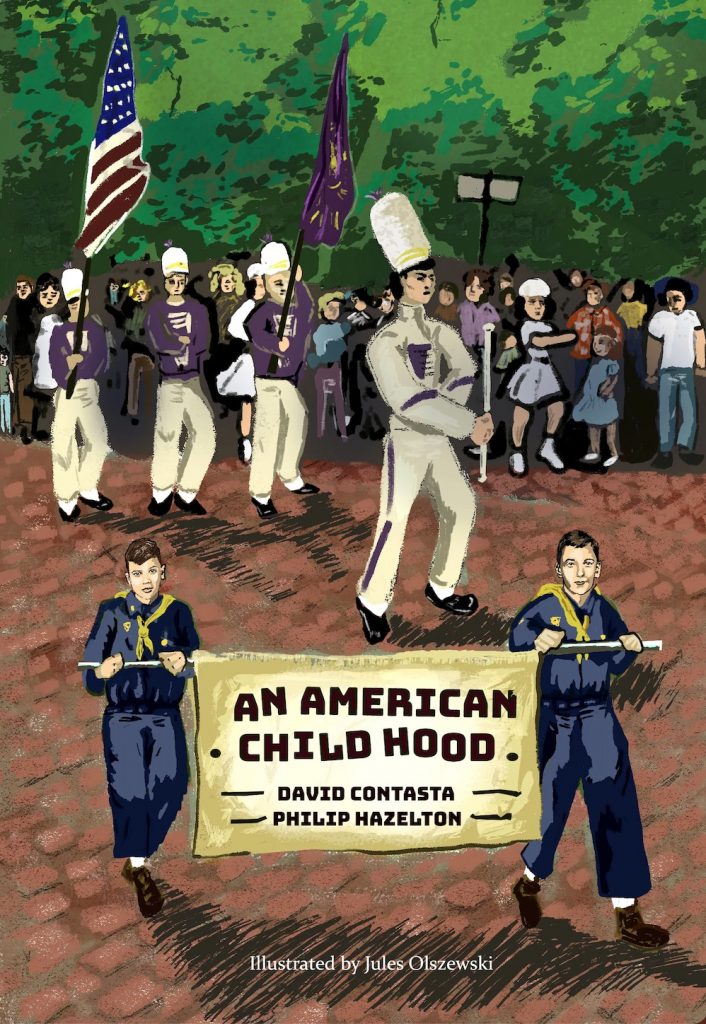

The result is “An American Childhood,” a volume of Hazelton and Contosta’s memories detailing everything from what it was like to attend elementary school in the ‘50s to the kinds of gender roles Hazelton and Contosta observed and saw enforced as children. Although Contosta and Hazelton never come out and say it in the book, the hometown where so many of these recollections unfold is none other than Lancaster, OH.

Sunday, October 16 at 1:30 p.m., Contosta returns to his hometown for an author talk and book signing at the First United Methodist Church (163 E. Wheeling St.) organized by the Decorative Arts Center of Ohio. Hazelton, who spent his life as a Presbyterian minister working in Ohio, Michigan, Maryland, Ohio, and South Africa, died in 2015.

Contosta is the Chair of the History Department at Chestnut Hill College in Philadelphia and the author of more than 20 books. He said he and Hazelton worked on the book in some way, shape, or form, for about 35 years. At the time of his cousin’s death, “An American Childhood” was in manuscript form, sitting on a flash drive in a drawer awaiting revision.

“So, I pulled it out and did some editing – and it was a joyful thing,” Contosta said. “It wasn’t really sad because [Hazelton] really seemed present in the words, in the pages of the book.”

One of the themes of “An American Childhood” is an extension of this – the understanding that one can live on not only through the memory of others, but also through stories they tell.

“We came from a family of storytellers,” Contosta said. “In the book, we talk about memory that goes back to other generations because of the stories they tell. And those memories become a part of who we are.”

One such memory Contosta has is of a neighbor who was born in 1860 and died in 1963, at the age of 103. She told Contosta she could remember the tintinnabulation of the church bells over Lancaster at the end of the Civil War.

“She made me realize that the Civil War was really not that long ago. And that I touched the life of somebody who not only was alive then, but who could remember the end of it. That’s called extended memory.”

Extended memory contextualizes one’s own experience. It can also reach a long way back.

“My grandmother, for example, grew up on a farm in 1890,” Contosta said. “They got around with horses. Her father used horses to plow. They had no electric lights, they had no telephone. She didn’t ride in a car for the first time until she was probably 15 or 16 years old. The Wright brothers didn’t invent the airplane until she was 13. And yet she lived to be 94. She died in 1984. She lived through the development of automobiles, through the development of the atomic bomb! She lived long enough to ride in an airplane and see human beings walk on the moon, which I think gives you some sense of the culture shock that that generation must have experienced.”

Perhaps, in part, it was the culture shock experienced by generations prior to the Baby Boomers which is at least partially to blame for what Contosta and Hazelton refer to as a “conspiracy of silence” about all things uncomfortable throughout their childhood.

“We talk in the book about the racism, the homophobia, the sexism, the social discrimination and so forth that existed throughout our childhoods, although it was not entirely apparent to us as children,” he said. “Most people we grew up with would’ve denied that there was any prejudice in Lancaster against African American people. But there certainly was. The whole topic of same sex relationships never came up. That was an entirely taboo subject. And it was assumed that women were happy being housewives and mothers. The idea that a woman would have a career was just impossible. I had a good childhood, but there were always a lot of things sort of swept under the rug.”

Contasta said that it was the norm to “not talk about unpleasantness of any kind.”

“I never even went to a funeral home for a viewing as a child, and I never went to a funeral, either,” Contosta said. “People didn’t talk about illnesses, particularly if they were serious. Divorce was also a very taboo subject – so was sex.”

From a contemporary standpoint, trying to hide racism, class struggles, sex, misogyny, and even death from a child is obviously damaging. Contosta said this gut reaction, effortless as it may seem now, not so long ago wasn’t the norm. This is because the tide began to turn – despite the efforts of many to stop it – around the time Hazelton started college in the ‘60s.

“Things changed because of the counterculture of the 1960s,” he said. “Just all the way around, there was an insistence on being honest about what was going on. And it wasn’t just parents who were hiding things from their children – the government was lying about the war in Vietnam. The counterculture really did open up a lot of topics that had been considered far too taboo to talk about.”

“Things changed because of the counterculture of the 1960s. Just all the way around, there was an insistence on being honest about what was going on. And it wasn’t just parents who were hiding things from their children – the government was lying about the war in Vietnam. The counterculture really did open up a lot of topics that had been considered far too taboo to talk about.” – David Contosta

While many things are radically different now than they were when Contosta was a child — some things are the same. One such thing is our human inclination to want to speed things up when we are young, and to drag our heels when we are old.

Perhaps one of the most poignant portions of “An American Childhood” comes at the tail end of chapter three, entitled “The Family Web.” As the authors finish up detailing their family’s specific annual customs for Christmas, they write “At the time, we took these family rituals for granted, and even grumbled about having to attend them as we grew older, supposing that they would go on forever.”

And isn’t that just the way it goes?

As Danish theologian Søren Kierkegaard once wrote “ Life can only be understood by looking backward; but it must be lived looking forward,” — or, as Joni Mitchell once sang “don’t it always seem to go, you don’t know what you got til it’s gone?”

For Contosta and Hazelton’s family, those Thanksgivings that at one time felt like they had been taking place at Hazelton’s mother’s home since before the beginning of time eventually did come to an end.

“We had Thanksgiving dinner there from 1952 to 2002 or 2003, for about 50 years,” Contosta said. “And for a number of years I returned to Lancaster from Philadelphia for them, and then for a number of years I took my own children to those dinners. And it went on so long that there was a sense that it would never end. And then Phil’s mother became somewhat infirm and had to go into a care home. And so that stopped. But for so long, there was a sense that these rituals were gonna go on and on and on forever. And then of course, I created my own rituals out here with my own children. I think that’s very important. And my children remember them. My son David particularly, wants to do things the same way as we always did, even though he’s in his early 30s now.”

David Contosta brings an author talk and book signing of “An American Childhood” to the First United Methodist Church (163 E. Wheeling St.) starting at 1:30 p.m. The event is sponsored by the Decorative Arts Center of Ohio. Admission is $15/$10 Decorative Arts Center of Ohio members prepaid registration, $20 at the door. Prepaid registration information at this link.