News

The CDC reports maternal deaths in the U.S. spiked in 2021

By: Selena Simmons-Duffin | Carmel Wroth | NPR

Posted on:

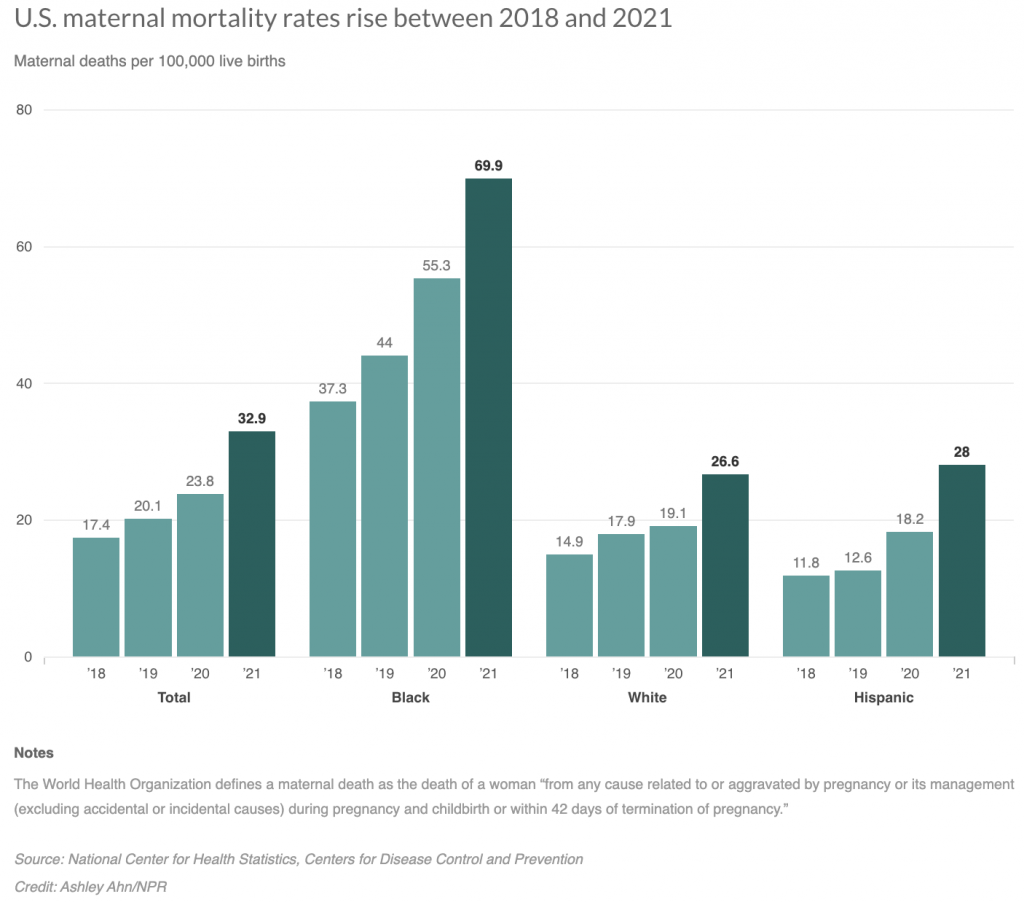

WASHINGTON (NPR) — In 2021, the U.S. had one of the worst rates of maternal mortality in the country’s history, according to a new report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The report found that 1,205 people died of maternal causes in the U.S. in 2021. That represents a 40% increase from the previous year.

These are deaths that take place during pregnancy or within 42 days following delivery, according to the World Health Organization.

The U.S. rate for 2021 was 32.9 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, which is more than ten times the estimated rates of some other high income countries, including Australia, Austria, Israel, Japan and Spain which all hovered between 2 and 3 deaths per 100,000 in 2020.

According to data from the World Health Organization, the maternal mortality rate in high-income nations overall was 12 per 100,000 live births in 2020, while in low-income countries it was 430 per 100,000.

International comparisons of maternal deaths are difficult because of differences in methodology in tracking the data, warns the author of the new U.S. report, Donna Hoyert, a health scientist at the National Center for Health Statistics, at the CDC. But, she notes, the U.S. is “usually not faring all that well” on maternal mortality.

“There is just no reason for a rich country to have poor maternal mortality,” says Eileen Crimmins, professor of gerontology at the University of Southern California. The CDC’s latest compilation of data from state committees that review these deaths found that 84% of pregnancy-related deaths in the U.S. were preventable.

The increase in maternal mortality in 2021 was “seen broadly across different age groups and race and Hispanic-origin groups,” says Hoyert.

She connects the increase in maternal deaths to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We had some forewarning with the increase between 2019 and 2020 that it looked like maternal mortality rates were increasing during this pandemic period,” she says. “With the overall COVID deaths that occurred in 2021, there was a shift towards younger people, so those would be in the age groups where people would be more likely to be pregnant or recently pregnant.”

She says provisional data suggest the deaths peaked in 2021 and started to go down last year. “So hopefully that’s the apex,” Hoyert says.

Yet some experts worry that other trends around the country could make these figures worse, not better, including abortion restrictions that can delay care for pregnancy complications, and staffing problems at hospitals and closures of rural maternity wards.

The maternal death rate among Black Americans is much higher than other racial groups; in 2021 it was 69.9 per 100,000, which is 2.6 times higher than the rate for White women.

Dr. Veronica Gillispie-Bell, an OB-GYN at Ochsner Health in Louisiana who works with the state’s health department to investigate maternal deaths, says social factors, not biological ones, fuel the racial gap. “We have to address the social factors that either are barriers to accessing care or that make your medical conditions worse coming into the pregnancy,” she says. “This is not just about doctors in the hospital.”

Louisiana is among a group of states working with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to improve processes in the health care system to prevent maternal deaths and reduce racial disparities. Gillispie-Bell says she’s optimistic the efforts will pay off, but “it’s not something that happens overnight. It’s going to be a while before we see the benefits of that change.”

Change can’t come soon enough for families whose lives are affected. Wanda Irving’s daughter died from complications of high blood pressure just three weeks after giving birth to a baby girl in 2017. Irving, who has spoken to NPR in the past about her daughter, now runs an organization called Dr. Shalon’s Maternal Action Project to raise awareness of the risks for Black mothers in particular.

Irving’s daughter, Shalon Irving, was an accomplished scientist, working as an epidemiologist at the CDC in Atlanta.

Wanda Irving tears up talking about her daughter’s final weeks. “She had gained 9 pounds in that last week. She was having headaches. One leg was bigger than the other and she said, ‘There’s something dreadfully wrong, can you please check.’ ”

Wanda Irving says her daughter’s death was preventable – she attributes it to racism within the health care system, to doctors ignoring her daughter’s symptoms and health risks.

Irving now lives in her daughter’s house and is raising her granddaughter, who’s now 6 years old, and bright, but struggles with her loss.

“There are days where she totally loses it and she breaks down and she’s in tears,” Irving says, saying her granddaughter will explain why she’s crying by saying, ‘I want my mommy. Can I die to go see my mommy?’ ”

Irving is working to raise awareness of the toll of maternal mortality, she says, because she doesn’t want another little girl or a little boy to grow up without their mother’s love.

“People need to understand the tremendous devastation that is caused by maternal mortality and the loss to society as well as to the families,” she says.

9(MDU1ODUxOTA3MDE2MDQwNjY2NjEyM2Q3ZA000))