Communiqué

The true story of early radical settlers; “The Pilgrims” on AMERICAN EXPERIENCE, Thursday, Nov. 16 at 10 pm

< < Back toRIC BURNS’ “THE PILGRIMS” TO AIR ON AMERICAN EXPERIENCE ON WOUB

NOVEMBER 16 at 10 pm

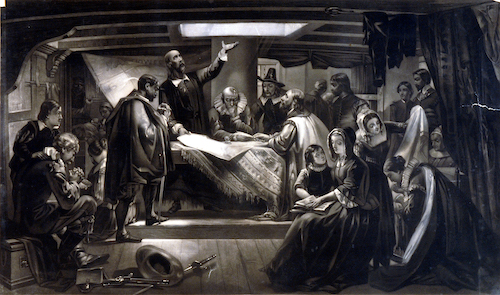

Stunning Recreations Bring to Life the Stark, True Story of America’s Early Radical Settlers

Features Final Film Performance of the Late Actor Roger Rees

“The Pilgrims,”a film by Ric Burns narrated by celebrated actor Oliver Platt, will air on AMERICAN EXPERIENCE on Thursday, November 16 at 10:00 PM. Produced by WETA Washington, D.C., and Steeplechase Films, in association with the BBC and CTVC, this two-hour documentary endeavors to tell the true story of the Pilgrims, a small group of religious radicals whose determination to establish a separatist religious community planted the seeds for America’s founding.

Arguably one of the most fateful and resonant events of the last half millennium, the Pilgrims’ journey west across the Atlantic in the early 17th century is a seminal, if often misunderstood episode of American and world history. “The Pilgrims” will explore the forces, circumstances, personalities and events that converged to exile the English group in Holland and eventually propel their crossing to the New World; a story universally familiar in broad outline, but almost entirely unfamiliar to a general audience in its rich and compelling historical actuality.

“From childhood on Americans are taught to think of the voyage of the Mayflower and the coming of the Pilgrims as the true founding moment of America,” said Burns, “and we honor them as such every year on Thanksgiving –even though they came thirteen years after the founding of Jamestown in 1607. The real story of the Pilgrims –who they were, what drove them on, what happened to them in the new world, how they succeeded and how they failed and why we remember them as we do –is far more gripping, poignant, harrowing and strange –and far more revealing –than the Thanksgiving myth we think we know.”

“When it comes to the Pilgrims, many people either believe in the mythologized Thanksgiving story, or they know that story isn’t really true so they cynically dismiss it entirely,” said Jeff Bieber, Executive Producer for WETA. “What gets lost, however, is the true, unvarnished history of the Pilgrims—one that is dark and deeply unsettling. It is about the transformation of a small band of English men and women into Colonists, with everything that this means for themselves and the Native population they encounter.”

“The Pilgrims”features spectacular recreations of the Mayflower’s harrowing voyage across the Atlantic using the Mayflower II, the only full-scale replica of the Pilgrims’ vessel in existence. Shot in only 90 minutes with three cameras, the scenes capture one of the rare times that the 60-year-old ship has been out on the open water. Recreations of the Pilgrims’ village were shot at “Plimoth Plantation,” a living history museum in Plymouth, Massachusetts, which served as a consultant throughout the production.

“As a museum with an educational mission to bring to life the history of the Pilgrims and the Native people of New England, Plimoth Plantation is thrilled to have collaborated in this production which will share this story with a wider audience,” said Ellie Donovan, Executive Director of Plimoth Plantation.

“The Pilgrims” also features a gripping performance by the late actor Roger Rees as William Bradford, the governor of Plymouth Plantation for more than 30 years and who wrote the definitive history of the early colony. Drawn from Bradford’s written account, Rees’s monologue provides the spine of the Pilgrims’ narrative, from the early formation of a separatist Protestant sect in England to a colony in the New World whose hard-fought success after a decade would trigger a massive influx of colonists throughout New England. Rees’s performance was his last on film before he passed away on July 10, 2015.

While Bradford’s account, written over 20 years, is a source of much of the narrative for “The Pilgrims,” his incomplete telling of their story is filled in by other Pilgrims’ writings and by court testimony that include some of the more harrowing and morbid details of their journey and settlement.Beginning in Scrooby, England in the early 17th century, the film traces the story of a small group of Protestants—led by minister John Robinson—as they decided to separate themselves spiritually, philosophically and physically from the Church of England and, by extension, the British monarchy.

As the film details, in the months following the Pilgrims’ arrival in the New World in 1620, they would face rampant starvation, disease and death. With people dying faster than they could be buried, they would prop up their sick and dead in the forests to appear as sentries to ward off potential attacks from native peoples—a transgression left out of most Pilgrims’ written accounts.

The Pilgrims’ relationship with the indigenous population was complex. They built Plymouth Plantation on a site littered with the human remains of the Wampanoags who had been wiped out by a plague that originated with European fishermen. They believed that God had cleared the ground for them to settle. Their first months were marked by a skirmish with the native people. But in their first spring, out of mutual desperation, the Pilgrims and the Wampanoags—who were also vulnerable to attacks from other tribes—agreed to support each other. Tisquantum, the sole survivor of the former village the Pilgrims now inhabited, lived with them to act as an interpreter and help them plant their crops.

In the fall of 1621, under Tisquantum’s supervision, the Pilgrims’ crops yielded a considerable harvest. To celebrate the bounty and an end to the hardships that had nearly killed them off, they held a three-day celebration of games and food. Massasoit, the Wampanoag’s leader, and 90 of his men joined them, contributing five deer they had killed. The event was not recorded by Bradford, and only a few paragraphs describe it in another account, which never uses the words “thanks” or “giving.” But more than two centuries later it would be imbued with new meaning and inspire a national holiday.

Despite their peace pact with the Wampanoags, the Pilgrims’ relationship with other tribes remained tense. Much to the dismay of John Robinson, for years they kept a decapitated head of a native person—a trophy from a bloody sneak attack the Pilgrims plotted—on a pike outside their village to instill fear in those who might attack them.

After years of struggle, the Pilgrims would eventually turn a profit for their investor, Thomas Weston, encouraging more and more colonists—Puritans, but not separatists—to venture to New England, where, in 1630, a trading port called New Boston was established. Within 15 years of Bradford’s death in 1657, approximately 70,000 English settlers arrived in New England, overwhelming the Native population of between 11,600 and 20,000, and the Wampanoag population of only 1,000. In 1675, Metacom, the son of Massasoit, who took the name “King Philip” in honor of the positive relationship his father forged with the Pilgrims, led an armed effort to drive out the colonists from Wampanoag land. In the end more than 600 colonists and at least 3,000 Native Americans died. Metacom was killed and the colonists placed his head on a pike over the Plymouth meeting house. They declared a “day of thanksgiving” to celebrate his defeat.

The film concludes with the trans-Atlantic hunt for Bradford’s manuscript, which was lost during the Revolutionary War and eventually turned up in England nearly a century later. Eventually it would be returned to Massachusetts and implant the Pilgrims’ story firmly into America’s origin narrative.