Communiqué

A lifelong fight for equality on and off the field: “Jackie Robinson” from Ken Burns. Part one airs Feb. 1 at 9 pm

< < Back toWOUB To Air “JACKIE ROBINSON”

February 1 at 9 pm

Two-Part, Four-Hour Film Chronicles the Life and Times of Robinson, His Breaking of Baseball’s Color Barrier and Lifelong Fight for Equality on and off the Field

President Obama, First Lady Michelle Obama, Harry Belafonte, Tom Brokaw and Others Reflect on Robinson’s Legacy

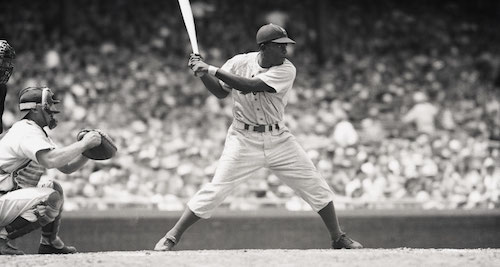

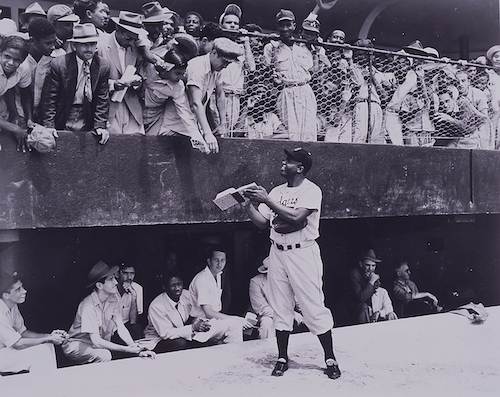

JACKIE ROBINSON, a two-part, four-hour documentary directed by Ken Burns, Sarah Burns and David McMahon, will air February 1st and 8th at 9:00 p.m. on WOUB. The film tells the story of Jack Roosevelt Robinson, who rose from humble origins to break baseball’s color barrier and waged a fierce lifelong battle for first-class citizenship for all African Americans that transcends even his remarkable athletic achievements.

“Jackie Robinson is the most important figure in our nation’s most important game,” said Ken Burns. “He gave us our first lasting progress in civil rights since the Civil War and, ever since I finished my BASEBALL series in 1994, I’ve been eager to make a stand-alone film about the life of this courageous American. There was so much more to say not only about Robinson’s barrier-breaking moment in 1947, but about how his upbringing shaped his intolerance for any form of discrimination and how after his baseball career, he spoke out tirelessly against racial injustice, even after his star had begun to dim.”

Born in 1919 to tenant farmers in rural Georgia and raised in Pasadena, California, Robinson challenged institutional racism long before he integrated Major League Baseball. As a teenager, he demanded service at a Woolworth’s lunch counter and refused to sit in the segregated balcony at a local movie theater. In 1944, while serving as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army, Robinson was arrested after he defied an order from a civilian bus driver to move to the back of a military bus. He was found not guilty.

In the spring of 1947, Brooklyn Dodgers General Manager Branch Rickey signed Robinson to a major league contract. To help ensure the success of their endeavor, and protect the big league prospects of future African-American players, Robinson agreed to ignore the threats and abuse that Rickey assured him he would face. That season, Robinson kept his word, remaining silent while he dazzled fans with his brilliant play and helped lead the Dodgers to the National League pennant. By the end of the year, he was the most famous black man in the country and in one poll, finished second only to Bing Crosby as the most popular American.

“Robinson is often celebrated for stoically ‘turning the other cheek’ to the threats and insults he faced during his first season in the majors, and what’s lost is that this display of self-restraint went completely against his character,” said co-director David McMahon. “This is a man who was court-martialed for refusing to move to the back of a military bus in 1944, a decade before Rosa Parks’s protest. He was feisty, assertive and naturally inclined to speak out against the slights and indignities he faced on and off the field, and we wanted to create a more nuanced picture of a man who is often reduced to a two-dimensional myth.”

In 1949, Robinson began to speak out, challenging opposing players, arguing with umpires and speaking his mind to the press, and he played some of the best baseball of his career, winning the National League MVP award. Despite his accomplishments on the field, his outspokenness drew criticism across the league, from the press and even from black fans and players who worried he would set back the progress that African Americans had achieved in baseball. When he retired in 1956, many were happy to see him go.

After baseball, Robinson continued to use his immense fame to elevate the civil rights movement, voicing his views through a widely read newspaper column, raising money for the NAACP and Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and campaigning vigorously for candidates he believed would work to improve the lives of African Americans. Meanwhile, in Stamford, Connecticut, the Robinson family faced the challenge of integrating schools, social clubs and Little League teams in their mostly white suburb, where residents and real estate agents had once tried to keep them from buying property.

JACKIE ROBINSON is also a warm portrait of a loving and devoted husband and father, featuring extensive interviews with Robinson’s widow, Rachel, and their surviving children, Sharon and David, who witnessed firsthand how resistant society could be to equality for African Americans, even their enormously popular father.

“We were incredibly lucky to have Rachel Robinson sit for three extraordinary on-camera interviews and open her personal archive of photographs,” said co-director Sarah Burns. “Her grace and eloquence elevate the family drama of their lives to a central focus in our film, and her recollections open up a window into Jackie’s private life that is rarely seen. Thanks to her contributions, and interviews with Sharon and David, the film is not only about baseball and civil rights, but is also a powerful portrait of an African-American family navigating the tumultuous 20th century.”

As the 1960s progressed, many African Americans grew frustrated with the slow pace of change in black neighborhoods, and new leaders began charting a more militant course for the civil rights movement. Robinson denounced their calls for progress by “any means necessary” and criticized them for rejecting integration. Some young African Americans accused Robinson of being out of touch — chiding him for his ties to Branch Rickey, New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller and other prominent whites — and sought new, more defiant cultural heroes such as Muhammad Ali and Jim Brown. But even as his celebrity waned and diabetes ravaged his body, Robinson continued to push for fair treatment and equal opportunities for all African Americans. After throwing out the first pitch before game two of the 1972 World Series, he told the crowd, and millions watching at home, that it was long past time for Major League Baseball to hire its first black manager. He died nine days later at just 53 years of age.

“Jackie Robinson,” Martin Luther King, Jr. once said, was “a sit-inner before sit-ins, a freedom rider before freedom rides.”

In addition to Rachel, Sharon and David Robinson, JACKIE ROBINSON features interviews with President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama; former Dodgers teammates Don Newcombe, Carl Erskine and Ralph Branca; writers Howard Bryant and Gerald Early; Harry Belafonte; Tom Brokaw; and Carly Simon. Jamie Foxx is the voice of Jackie Robinson, reading excerpts from his newspaper columns, personal letters and autobiographies.

JACKIE ROBINSON is a production of Florentine Films and WETA, Washington, DC, in association with Major League Baseball. It is directed and produced by Ken Burns, Sarah Burns and David McMahon; written by David McMahon and Sarah Burns; edited by Lewis Erskine, A.C.E., George O’Donnell and Ted Raviv; cinematography by Buddy Squires, A.S.C.; original music by Wynton Marsalis and Doug Wamble; narrated by Keith David. Series advisors include Kevin Baker, Adrian Burgos, William E. Leuchtenburg; John Thorn, Khadijah White and Craig Steven Wilder.