Communiqué

New frontiers for working women and the constraints of traditional notions of femininity in “Fly with Me” on AMERICAN EXPERIENCE – Feb. 20 at 9 pm

< < Back toAmerican Experience: “Fly With Me”

Premieres Tuesday, February 20 on PBS and Streaming on PBS.org

Documentary Explores the Lives of the Pioneering Women Flight Attendants Who Transformed the World While Flying It

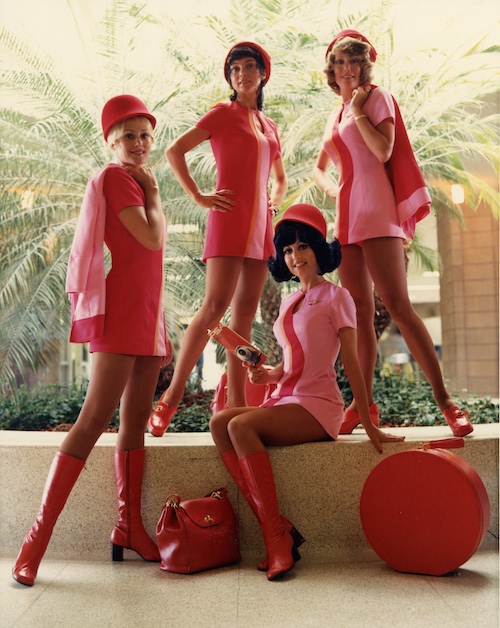

A cabin attendant was considered a man’s job at the dawn of the commercial airline industry. But by the 1950s, as planes became safer and more reliable, stewardesses became a critical selling point for airlines fighting for market share in a heavily regulated industry.

Credit: United Airlines

At a time when single, middle-class women were expected to marry and raise a family, becoming a stewardess offered remarkable opportunities. The job required glamour, intelligence, independence and grit. But there were downsides. The airlines required every stewardess to be young, single and attractive, which, in 1950s America, meant white. Pat Banks, who failed to land even one interview after successfully completing a stewardess training program in 1956, filed a complaint with the New York State Commission on Discrimination. After four years, she won and was hired by Capital Airlines, making her one of the first Black flight attendants in the U.S.

The airlines didn’t discriminate solely on the basis of race. Stewardesses could not be married and were forced to retire as early as age 32. Weight and height guidelines were strictly enforced; women could not wear eyeglasses and had to share hotel rooms, unlike their male counterparts. Barbara “Dusty” Roads decided to fight back. She joined her labor union, lobbied Congress and strategically courted media attention. But without a federal law prohibiting workplace discrimination, it was an uphill battle.

Then on July 2, 1964, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act. Designed to address race-based inequalities in American life, the law also included a clause offering worker protections against gender discrimination. On the day the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, set up to enforce the new anti-discrimination laws, opened, Dusty Roads and her best friend Jean Montague filed a complaint against the airlines’ age limit. Within a year of the EEOC’s opening, nearly 100 cases citing gender discrimination had been submitted by flight attendants.

But the commission made few rulings, fueling concerns that gender complaints were not being taken seriously by the mostly male EEOC leadership. Frustrated in part by the commission’s inaction and a society-wide lack of progress in the fight for equal rights, activists formed the National Organization for Women. The organization demonstrated, filed lawsuits and pressured the EEOC to act.

Credit: San Diego Air & Space Museum

Just as stewardesses were gaining momentum in their fight for workplace rights, airlines transformed their ad campaigns. Once marketed as glamourous hostesses in the sky, now they were being presented as sex objects. At the same time, as the Vietnam War intensified, stewardesses often found themselves on the frontlines, flying in and out of Saigon to shuttle troops back and forth. “You’re being marketed, basically, as a Barbie doll, and yet doing more and more complex work,” historian Phil Tiemeyer explains. “There’s a fundamental incompatibility between these two things.”

In 1972, a group of flight attendants founded Stewardesses for Women’s Rights. Journalist and trailblazing feminist Gloria Steinem actively promoted their cause, recognizing the vital role these high-profile working women could play in the burgeoning Women’s Movement.

When stewardess Mary Pat Laffey fought to become the first female purser at Northwest Airlines, the company cut her salary, paying her less than her male counterparts. Laffey filed a class action lawsuit in 1970. By the time the case went to trial, 70% of Northwest Airlines stewardesses had become part of the lawsuit. In 1974, the judge ruled in favor of Laffey and the stewardesses, awarding them a large payout for back salary with interest and reimbursement for the difference in room rent — stewardesses had been required to double up in hotel rooms while stewards had single rooms. The decision also struck down rules against wearing glasses and weight limitations, which targeted only women.

Northwest appealed. It took another 11 years before the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the ruling in favor of the women, who were awarded $60 million in the case. “Women were finally allowed to have the same benefits that the men had,” explains Laffey. “If you were capable, you could have a man’s job.”

“The women of Fly With Me broke barriers by becoming flight attendants in the first place, but what is so remarkable is that they were also on the vanguard of fighting for workplace equity,” said Colt. “By exploring this history, we show the power of individuals to make change and how gender, race and class are critically intertwined.”

Credit: United Airlines

American Experience films stream simultaneously with broadcast and are available on all station-branded PBS platforms, including PBS.org and the PBS Video app, available on iOS, Android, Roku, Apple TV, Amazon Fire TV, Android TV, Samsung Smart TV, Chromecast and VIZIO. All titles will also be available with closed captioning in English and Spanish.

Flight Attendants and Legal Advocates Featured in the Film:

Patricia “Pat” Noisette Banks Edmiston became one of the first Black flight attendants in 1960, four years after filing a lawsuit with the New York State Commission on Discrimination. She retired after one year and went on to raise two children while working for the New York State Office of Alcohol and Substance Abuse. She was inducted into the Black Aviation Hall of Fame in 2010.

Celeste Lansdale Brodigan became a flight attendant at United Airlines in 1962. She was secretly married for four years before the airline found out and terminated her. Celeste filed a grievance with her union, brought her complaint to the EEOC, filed an injunction and lawsuit, and finally took her story to The Miami Herald. Celeste won her lawsuit and worked for United Airlines for 35 years, flying military air charters during the Vietnam and Gulf Wars.

Michael Gottesman is an expert in labor law and represented Mary Pat Laffey in her class action lawsuit against Northwest Airlines. He currently teaches at Georgetown Law School.

Casey Grant became one of Delta’s first African American flight attendants in 1971, working for the airline for 35 years. She hosts a radio show and writes books about African American pioneers in aviation.

Kathleen Heenan flew for TWA for 12 years and was an active member of Stewardesses for Women’s Rights. She raised three children and went on to teach a birding program in New York City public schools.

Ann Hood flew with TWA for eight years. She published her first novel in 1987 and has written more than a dozen award-winning books including Fly Girl, her recently published memoir about her career as a flight attendant.

Patricia Ireland attended law school while working as a flight attendant at Pan Am. After seven years with Pan Am, she began her legal career. In 1991, she became president of the National Organization for Women (NOW).

Mary Pat Laffey Inman was an active leader in her union and fought to become the first woman hired as a purser by Northwest Airlines. In 1970, she organized her fellow flight attendants to file a class action lawsuit to demand equal pay and treatment for women working as flight attendants and pursers at the airline. After more than a decade of appeals by Northwest, in 1984 the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the ruling in her favor.

Undra Mays was hired in 1970 by National Airlines where she faced workplace discrimination because she was Black. With no recourse within her company or union, she contacted The Southern Poverty Law Center. She was later chosen to participate in the “Fly Me” National ad campaign, one of only a few Black women featured. She retired in 2020 after 50 years of flying.

Jean Montague filed a discrimination complaint against American Airlines for requiring flight attendants to retire at age 32. She retired from American Airlines after nearly 40 years as a flight attendant. While working as a flight attendant, Jean earned her pilot’s license at the age of 53.

Sonia Pressman Fuentes joined the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) on October 4, 1965, three months after the agency opened. She was the first woman attorney in the office of the General Counsel. One of the founding members of the National Organization for Women (NOW), she fed inside information about the EEOC’s lack inaction on cases involving gender discrimination to NOW.

Barbara “Dusty” Roads (1928-2023) fought against American Airlines’ mandatory retirement age for women. She lobbied members of Congress on flights to Washington, DC, and staged press conferences to see if reporters could pick out the 32-year-old flight attendants in a lineup. In 1977, she co-founded the Association of Professional Flight Attendants, which now represents over 26,000 people. Roads worked for American Airlines for 44 years.