Communiqué

A career exploring how to harness the sun’s power in “The Sun Queen” on AMERICAN EXPERIENCE – March 12 at 9 pm

< < Back toAmerican Experience The Sun Queen

Tuesday, March 12 at 9:00 pm, on PBS and Streaming on PBS.org

New Film Explores the Fascinating Life of the Solar Energy Pioneer Mária Telkes, Known as “The Sun Queen”

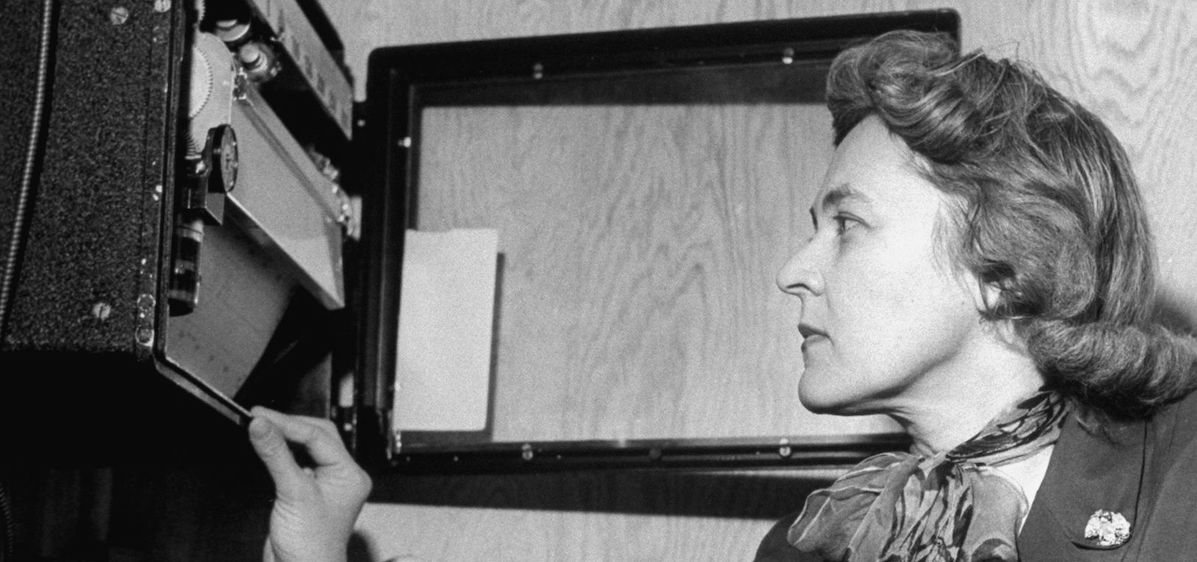

For nearly 50 years, chemical engineer and inventor Mária Telkes applied her prodigious intellect to harnessing the power of the sun. She designed and built the world’s first successfully solar-heated modern residence and identified a promising new chemical that, for the first time, could store solar heat like a battery. And yet, along the way, she was undercut and thwarted by her boss and colleagues — all men — at MIT. Despite these obstacles, Telkes persevered and, upon her death in 1995, held more than 20 patents. She is now recognized as a visionary pioneer in the field of sustainable energy. An unexpected and largely forgotten heroine, Telkes was remarkable in her vision and tenacity — a scientist and a woman in every way ahead of her time. Her research and innovations from the 1930s through the ‘70s continue to shape how we power our lives today. Produced and directed by Amanda Pollak, produced and written by Gene Tempest, and executive produced by Cameo George, The Sun Queen premieres Tuesday, March 12, 2024, 9:00-10:00 p.m. ET on PBS, PBS.org and the PBS App.

“It is the things supposed to be impossible that interest me,” Telkes once explained. “I like to do things they say cannot be done.” Her driving ambition was to design practical inventions that would use the sun to benefit humanity writ large. Born in Hungary in 1900, she earned a doctorate in physical chemistry at age 24 and emigrated to the U.S. in 1932, to be a part of the burgeoning field of solar energy. When MIT launched its Solar Energy Fund in 1938, aimed at bringing together the best minds in the field, Telkes immediately wrote to the university president, asking to join the team. She got the job.

The timing was precipitous. Soon, with the country entering World War II, resources were tightly rationed and the idea of creating housing that could run without coal or oil was more urgent than ever. Telkes threw herself into the war effort along with the head of the solar project, a fuel engineer named Hoyt Hottel. Their task: to develop a solar desalinator for downed pilots in the Pacific theater.

When the war ended, America faced a new challenge: creating affordable housing for the millions of returning G.I.s who were starting families. With energy still scarce, it seemed like the time for solar had arrived. Telkes devoted her energies to developing a prototype house that could be heated entirely by the sun. There had been other attempts at solar housing, but no matter how well they worked on sunny days, they could not hold heat overnight. “The problem of solar energy,” explained Telkes, “is storage.” Her solution was a chemical compound that could store solar-generated energy. Hottel allowed Telkes to use the process in their next experimental house. When the system failed, she was removed from the project.

Telkes was undeterred. If she couldn’t find support for her work in the male-dominated halls of MIT, she would find new backers who shared her passion and vision. Amelia Peabody was a wealthy Boston philanthropist; Eleanor Raymond was a pioneering architect. Together with Telkes, they formed an all-woman dream team and built what became known as the Dover Sun House, in Dover, Massachusetts.

Completed in 1948, the Dover Sun House was, unlike earlier prototypes, designed to be lived in by a family; that Christmas, the Nemethys, a Hungarian émigré family, moved in. It was soon one of the most famous houses in the country, and Telkes became a media celebrity. The “Sun Queen,” as she was known in the press, fast became the nation’s most visible face of the solar future. That fame, which Telkes leveraged to further the solar cause, came at a cost. The boys’ club at MIT was unimpressed by her latest project and, in 1953, she was fired.

Still, Telkes persisted. She created a solar-powered oven that is still in use and continued to push her vision of solar housing for the masses. But by the mid-50s, the Dover Sun House began to fall into disrepair. Materials corroded and systems failed. Undeterred, she refused to see the experiment as a failure and continued to work on refinements.

But the quest for solar solutions was sidelined by the much-publicized failure of the Dover Sun House and an American economy fueled by cheap and abundant petroleum. The age of fossil fuels had arrived. As scholar Olivia Meikle says, “What really is the tragedy here is what she could have accomplished. We won’t ever be able to know what she could have done. Maybe she could have made these huge leaps. Maybe we could have been a decade or two ahead on solar power from where we are now.”

Cameo George, executive producer of American Experience, says: “We could be living in a very different world today if we had followed up on her inventions. I think there are a lot of viewers — not just women, not just girls — who will be inspired by her story, but also wonder why they haven’t heard of her until now.”