News

Vinton’s ‘loud and proud’ approach to overdose awareness sees a massive reduction in deaths

By: Theo Peck-Suzuki | Report for America

Posted on:

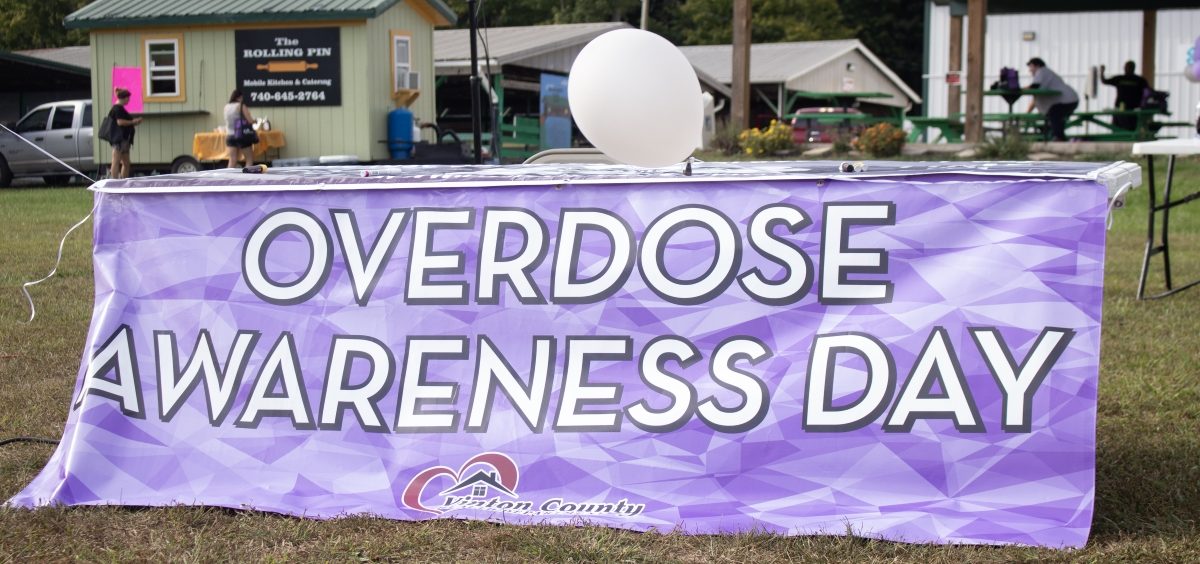

MCARTHUR, Ohio (WOUB/Report for America) — Anyone taking State Route 93 east out of McArthur Thursday evening might have thought there was a party at the county fairground.

There were tents, a food truck and a large inflatable water slide. Loudspeakers blared a mix of popular songs like Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell’s “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough.” There were even giveaways – but these weren’t your typical party favors. Instead, the Vinton County Health Department was handing out NARCAN and fentanyl test strips.

This was Vinton County’s Overdose Awareness Day. As the rise of fentanyl added new fuel to the decades-old opioid epidemic, Vinton suffered one of the highest fatal overdose rates in the state — until, that is, a new health department program reversed the county’s fortunes.

The Post-Overdose Recovery Team, or PORT, started in mid-2023. Its members visit overdose survivors to offer resources (which are optional), and they are engaged in other efforts involving stigma reduction and expanding access to NARCAN. Vinton recorded 20 overdose deaths the year before PORT’s founding; this year so far, it has recorded only one.

Thursday’s event was an opportunity to celebrate this accomplishment and push the work further.

“My main goal is to spread the word. It’s on the back of our shirts: no more shame, no more stigma. Stigma is what keeps people from getting help,” said PORT coordinator Melanie Carte. “We are here to train people with NARCAN, hand out a lot of NARCAN, that way people do have a chance to make different decisions and actually change eventually.”

That’s a chance some of her friends never had.

“I had friends that passed. It (NARCAN) was not there. It wasn’t in the people’s hands,” Carte said.

“When I first started at the health department, there was a lot of politics and a lot of people that were against NARCAN,” Carte recalled.

That changed after a big funding boost from, in part, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Then we had a reason to kind of not ask permission anymore and just go out there and do the harm reduction things we needed to do,” she said.

“People are getting more knowledgeable, people are understanding more. It touches more lives, and that causes people to have more compassion, hopefully,” she added. “I have a lot of hope that it keeps getting better.”

Carte’s colleague Bonnie Campbell, who supervises Vinton’s Help Me Grow program, put it more bluntly.

“Until it falls dead in your bathroom, you don’t know,” she said.

That’s what happened to Campbell’s son — except he did not die, thanks to the speed of the first responders, who showed up with NARCAN. Campbell now advocates passionately for keeping a bottle of NARCAN in one’s car, just in case.

“You never know. You might pull into a parking lot, and you look over and there’s somebody sitting in a seat and you know they’re overdosed,” she said. “Had it happen many times, especially at the Walmart parking lot. And, you need to have that. You can save someone’s life.”

Recovering from substance use disorder

Today, Campbell’s son is behind bars. She said he didn’t stop using.

“This might sound crazy, but I’ve always been loud and proud about the fact that, yes, I have someone who’s addicted, but he is my child,” Campbell said.

“Am I thankful he’s locked up? Yes, because I know he’s safe,” she added. “But I’m never ashamed of my child, or the fact — everybody knows my son, and everybody knows he’s an addict. This is a small town. … It’s imperative that we understand, and that we learn. Listen, come and say that you are. Families, come out and say you need help.”

Carte said substance use disorder first took hold of her life when she was in college.

“It started pretty much with Adderall. I got sick kind of young with endometriosis, so that started with the painkillers,” she recalled.

Carte kept her condition a secret for a long time, but after she developed Crohn’s disease, her situation deteriorated.

“It was a really dark place for me. A really hopeless place and a really scary place, and that’s when it kinda spiraled out of control. I found it was not that easy to just stop when the doctor said stop,” she said.

Eventually, Carte got in legal trouble and lost her job. With nothing but time to sit and think, she said, she realized she wasn’t listening to what her inner self was telling her she needed.

“So I knew I needed to make changes and I had a lot of time on my hands, so there I started, from the bottom. Digging your way out of all the mucky-muck,” she said.

Today, Carte pays a visit to anyone who survives an overdose in Vinton County. She doesn’t pressure them to accept services, but she does crack the door open in case they’re ready to step through.

“I just want to show up and say, ‘Hey, I’m glad you made it. We’re here,’” Carte said. “When I think back, there was a lot of days I wouldn’t have answered my door. Some days, I would’ve cussed. And then some days, I would’ve been just so ragged and wore out from it, I would’ve been like, ‘Yeah. Help me out.’”

“We’re not living in the same generation as we were before where you could try something,” Carte said. “It’s even in marijuana. It’s really scary to me.”

“It just takes one pill, one joint, one time. And you will lose your whole life,” she added.

Addiction, Carte said, “feels like walking through hell.” But she also knows firsthand why it’s so hard for people to stop. There’s the physiological component: Substance use disorder affects the brain and changes a person’s body. And there’s a psychological piece, as well.

“That’s the devil they know,” Carte explained. “It’s so much scarier to go out there in the unknown.”

And yet, Carte said, “It is so worth it. You get your relationships back. You get your health back. I did things that … I would’ve never imagined being paid for those experiences and going out here and helping people. That was never even part of my dreamscape. And now I’m doing that.”