News

Ohio has designated the majority of its American Rescue Plan Act funds. Here’s where the money is going

By: Kendall Crawford | The Ohio Newsroom

Posted on:

COLUMBUS, Ohio (Statehouse News Bureau) — Billions of dollars came to Ohio through the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) to help mitigate the impact of the coronavirus in 2021. Now, three years later, the majority of the state’s coronavirus relief funds have been committed to a cause.

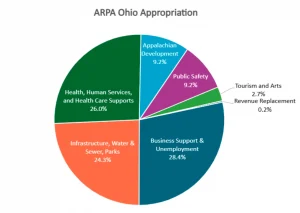

More than 87% of the state’s $5 billion has been assigned, with the biggest chunks going toward water and sewer projects, health and human services and unemployment support.

“The long term outcome of many of these investments will be seen years from now and may transform communities,” said Susan Jagers, director the Ohio Poverty Law Center, who helps run the Ohio ARPA Tracker.

The state has until the end of the year to commit all of its funding, then another two years to distribute the money. More than half of the money – totalling around $3.2 billion – has already gone to communities across the state.

State’s successes with American Rescue Plan funds

There was a lot of flexibility in how the ARPA funds could be spent, said Dylan Armstrong, public policy fellow with the Center for Community Solutions, a nonpartisan think tank focused on human health services. Beyond emergency relief, the money could replace lost public sector revenue, go toward infrastructure projects and support transportation projects.

“[Some] water and sewer grants went to small, rural communities and helped extend safe water to homes that may not have had that option in the past,” Jagers said.

The state also allocated $150 million toward lead remediation, portions of which went toward training contractors on lead abatement practices. Another $84 million was invested in expanding behavioral health resources for children by creating more inpatient facilities. And around $77 million was spent on expanding broadband to underserved areas of the state.

Ohio invested more in economic development and fighting unemployment than in health and human services. Nearly 30% of the funding went toward business and tourism. The Appalachian region of the state was of particular focus. The state committed $500 million in community development grants to southeast Ohio.

Room for improvement

Despite the large pot of money, not every organization’s requests were filled. Advocates requested more than $300 money to support affordable housing in the state, but just around $25 million went toward the issue. The Ohio Association of Foodbanks requested $183 million to aid its food assistance programs, but only received $40 million.

The state also didn’t invest much in minority health and reducing racial disparities, according to Armstrong’s analysis. He believes more money should’ve been allocated toward equity initiatives, given people of color were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic.

“ARPA funding was meant to be very transformative. It was supposed to be for really big ideas,” Armstrong said. “And I think the state, while putting it toward many things that do deserve funding, didn’t go as far as they could have gone with really trying to address some of these inequities.”

Lessons learned

This isn’t the first time Ohio has received a large pot of money to invest in the state – and it likely won’t be the last.

Armstrong said the state has shown a willingness to learn from its past mistakes. The ARPA funding didn’t fall into some of the same pitfalls as the state’s tobacco master settlement – where funding for tobacco prevention was used for other political priorities.

“I think when a pot of money of this size comes along again, which it will eventually, we should be optimistic that our concerns should be heard,” Armstrong said.

In the future, though, Armstrong would like to see stronger public input. Some of the state’s ARPA funds were designated through executive action or by the state’ controlling board, making it difficult for some advocates to make their argument for a slice of the funding.

“Other states had done a more comprehensive planning process when it came to their ARPA funds. The state of Ohio chose not to.”