Communiqué

Go beyond the legend to meet the woman who risked her own life to liberate others; “Harriet Tubman: Visions of Freedom” – Dec. 12 at 10 pm

< < Back toHARRIET TUBMAN: VISIONS OF FREEDOM

Thursday, December 12 at 10 pm on WOUB

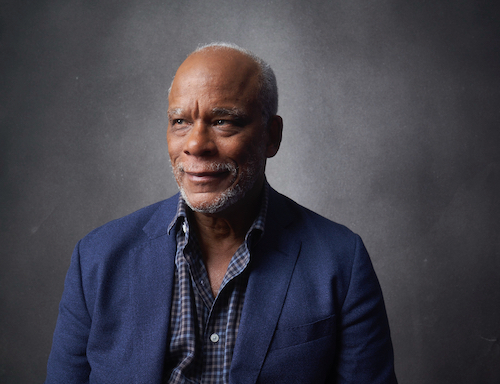

Directed by Oscar®-Nominated Filmmaker Stanley Nelson and Nicole London and Narrated by Emmy® Award-Winning Actor Alfre Woodard with Acclaimed Actor Wendell Pierce as the Voice of Frederick Douglass

The documentary HARRIET TUBMAN: Visions of Freedom is a rich and nuanced portrait of the woman known as a conductor of the Underground Railroad, who repeatedly risked her own life and freedom to liberate others from slavery. Born in Dorchester County, Maryland—2022 marks her bicentennial celebration—Tubman escaped north to Philadelphia in 1849, covering more than 100 miles alone. Once there, she became involved in the abolitionist movement and, through the Underground Railroad, guided an estimated 70 enslaved people to freedom. She would go on to serve as a Civil War scout, nurse and spy, never wavering in her pursuit of equality. Featuring more than 20 historians and experts and grounded in the most recent scholarship, HARRIET TUBMAN: VISIONS OF FREEDOM goes beyond the standard narrative to explore what motivated Tubman, including divine inspiration, to become one of the greatest freedom fighters in our nation’s history.

A co-production of Firelight Films and Maryland Public Television (MPT), the film is executive produced by Stanley Nelson and Lynne Robinson and produced and directed by Nelson and Nicole London. Oscar-nominated and Emmy Award-winning actor Alfre Woodard narrates the documentary, and acclaimed actor Wendell Pierce provides the voice of Frederick Douglass.

“With this film, our aim was to go beyond what is covered in history books to create a real, three-dimensional portrait of who Harriet Tubman actually was,” Nelson said. “We wanted to examine what motivated her to pursue a revolutionary and often dangerous journey, particularly through her fierce religiosity and metaphysical connection to the divine. This film also has such a distinct sonic layer thanks to powerful narration by the great Alfre Woodard.”

“One of the things that Harriet believed was that God didn’t mean for anybody to be a slave. Freedom should be universal.” – Historian Karen Hill

Born “Araminta” in 1822 to an enslaved couple on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, Harriet Tubman learned quickly about the cruelty of life as a slave. By the time she was 5, her duties included catching muskrats in the swamps, cleaning the slaveowner’s house and babysitting their colicky infant. Each time the baby cried, Tubman would be whipped.

The young girl preferred working outdoors and relished any chance to work outside alongside her father, Ben Ross, who was forced to live apart from the family because he was enslaved by different owners. Because of the tremendous growth of cotton production in the Deep South, the threat of being sold to slaveowners there was an ever-present fear. “Enslaved people in Maryland knew that that was a death sentence,” says Tubman biographer Dr. Kate Clifford Larson. “The average lifespan for an enslaved person who was purchased in the Chesapeake and brought to Mississippi or Louisiana was about seven years.” Tubman witnessed the horror firsthand, watching as her older sisters were dragged away in chains—a memory that would haunt her for the rest of her life.

The young girl preferred working outdoors and relished any chance to work outside alongside her father, Ben Ross, who was forced to live apart from the family because he was enslaved by different owners. Because of the tremendous growth of cotton production in the Deep South, the threat of being sold to slaveowners there was an ever-present fear. “Enslaved people in Maryland knew that that was a death sentence,” says Tubman biographer Dr. Kate Clifford Larson. “The average lifespan for an enslaved person who was purchased in the Chesapeake and brought to Mississippi or Louisiana was about seven years.” Tubman witnessed the horror firsthand, watching as her older sisters were dragged away in chains—a memory that would haunt her for the rest of her life.

Around age 13, Tubman suffered a blow that would forever change her life. When an overseer threw a heavy weight at an enslaved boy, the weight instead hit Tubman. Her skull was fractured, and from that day forward, she suffered from seizures and horrific headaches. During these episodes, she would have visions, which she understood as signposts from her God.

After she regained her health, she offered her owner, Edward Brodess, a deal—she would pay him a yearly fee for the privilege of hiring herself out to masters of her own choosing. She began working the docks, building her strength. Eventually, she was allowed to work in the forest with her lumberjack father and became even stronger and more capable. She also developed a deep understanding of her landscape and surroundings—skills about to come in very handy.

In 1849, Brodess died, leaving his widow deeply in debt. After watching the widow sell one group of enslaved people at auction, Tubman decided to run, leaving behind everything she knew.

On September 17, 1849, Tubman stole away into the night with her two brothers, who soon changed their minds, so the three went back. Within days, she set out again—alone. This time, there would be no turning back.

“There was one or two things I had a right to, liberty or death. If I could not have one, I would have the other.” – Harriet Tubman

Traveling alone and mostly at night, Tubman made a journey of about 100 miles through woods, marshes and swamps from the Eastern Shore of Maryland to Philadelphia. She made her way to a group of Black abolitionists led by William Still, regarded as the Father of the Underground Railroad, who debriefed runaways, gathering intelligence that would help others make the journey to freedom.

But with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850, escaping became even more dangerous. The new law made it a federal crime to offer food or shelter to a runaway, and any citizen in any state, North or South, was compelled to report an alleged fugitive to the authorities.

Undaunted, Tubman chose to help free as many people as she could, making at least 13 secret missions into slave-holding Maryland and using every tool at her disposal—traveling in the winter months when nights were longer and employing disguises and deception to evade enslavers and bounty hunters. These journeys were made possible by the loose-knit secret network of ordinary people called the Underground Railroad. Her vision of freedom became a reality for at least 70 people.

Within months of President Abraham Lincoln’s election, the Southern states seceded and the simmering argument over slavery erupted into armed conflict. Tubman dived into the Civil War effort, lecturing, nursing, and encouraging Black men to aid in the cause. But she wanted to do more. She became a spy, leading a team of eight Black scouts and gathering critical intelligence for the Union Army.

In June of 1863, Tubman set into motion one of the most daring and successful raids of the war at Combahee Ferry in South Carolina. At least 727 enslaved men, women and children made it onto the Union boats, making the raid one of the largest liberations of the war—and marking the first major military operation in American history that was planned and executed by a woman.

Following the war’s end, Tubman returned to the home she had purchased in Auburn, New York, to take up the struggle in new ways. She used her home to shelter elderly, formerly enslaved people and became a suffragist for women. In 1913, at the age of 91, Harriet Tubman died.

Harriet Tubman left behind an audacious legacy. With her work on the Underground Railroad and during the Civil War, she helped hundreds of African Americans escape enslavement. Says historian Marcia Chatelain, “Harriet Tubman is a hero because she does not have a blueprint for freedom. But what she has is incredible conviction and an incredible will to unmask the brutality of slavery and to fight against it.”