News

The Flood Next Time: Warming Raises The Risk Of Disaster

By: Glynis Board | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

People in West Virginia are still recovering from floods that tore through communities like vengeful gods. When you look at the pictures and videos of the June flood – thick, brown, furious, unrelenting – it’s not hard to imagine how our ancestors believed supernatural beings were behind the devastation. Today, of course, we have better insight into the natural forces at work, and science shows us that the damage from nature’s wrath has a lot to do with human behavior.

The National Weather Service described the West Virginia disaster as a 1000-year event, a term meteorologists use to describe the rare probability of such extreme rains. Many scientists who study the climate, however, warn that our warming atmosphere is increasing the likelihood and severity of flooding disasters. Further, a review of emergency planning shows that while risk of extreme rainfall is on the rise in Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia, the states are not doing enough to prepare for the rising waters.

The Science

“Data are very clear,” said Michael Mann, Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Science at Penn State University. “There is a substantial increase in what we call the intensity of rainfall events,” he said, “which is simply to say, flooding – more extreme and more prevalent flooding.”

NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, reported that last month was the warmest June for the U.S since temperature record-keeping began more than a century ago, and 2016 is on track to become the globe’s warmest year ever recorded. Mann explained that our atmosphere is like a sponge, and the warmer it is the more water it can hold.

“When you squeeze that sponge you’re going to get more intense rainfall events, more intense flooding,” he said. “And the data indicate that this is indeed happening in the U.S.”

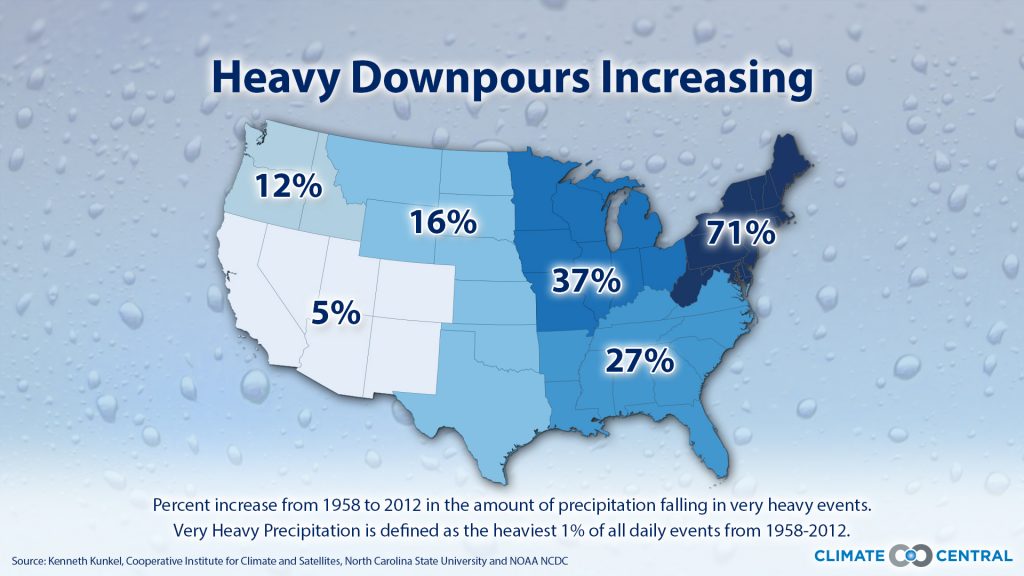

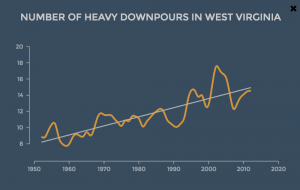

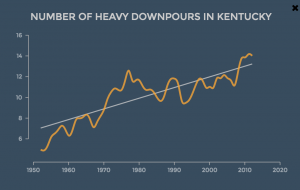

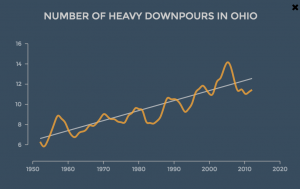

A report by NOAA and some sixty other scientific agencies shows that intense rainstorms have increased significantly in many parts of the country over the past half-century. In West Virginia and parts of the northeastern U.S., the proportion of precipitation that comes down in the heaviest storms went up by 71 percent. In Kentucky and Ohio, those heavy storms are up by about a third over the same time period. And climate forecasts show a strong likelihood that those trends will continue as the planet warms further.

The Cost

That’s bad news for Appalachia, which is the region most prone to flash-flooding in the country, and maybe even the world. The Pew Charitable Trusts found that flooding is the fastest-growing and most costly type of natural disaster across the country and the National Flood Insurance Program is nearly $24 billion in debt. The Federal Emergency Management Agency found that eight weather events in the U.S. have cost more than $13 billion in property losses so far this year, to say nothing of lives lost.

Director of the Office of External Affairs at FEMA, Josh Batkin, said his organization is working to adjust to increasing numbers of disasters.

“We’ve come up with this idea of a ‘disaster deductible’,” Batkin said.

The idea FEMA is developing would have each state pay a predetermined financial commitment in order to receive the public assistance funding made available after disaster declarations. Batkin said this would create another way to reward states for investing in disaster preparedness.

“We would provide [states] with credit toward their deductible amount for doing what needs to be done to make people safer and to protect infrastructure,” Batkin said.

With other changes going into effect this year FEMA requires an assessment of the risks posed by climate change to be included in the hazard mitigation plans states must submit to the agency. This means states won’t just be considering the threats based on past disasters; the risk analysis will now also account for how climate change could increase future events such as flooding.

Plans are updated on a five-year cycle, with varying deadlines among the states. In Kentucky, for example, the new plan wouldn’t be due until 2018. An independent review of state-level planning and risk indicates that such changes are overdue in the Ohio Valley.

Tomorrow’s Floods

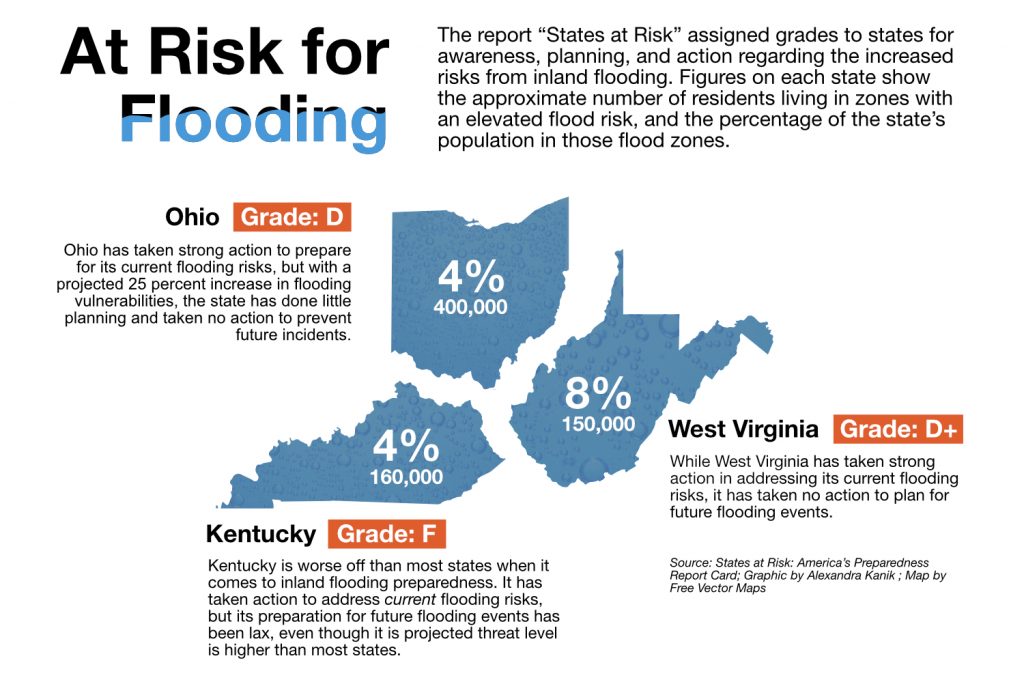

The nonprofit Climate Central, which offers scientific research and information on climate change, produced a report last November called States at Risk: America’s Preparedness Report Card. The report rated states on how well each is preparing for predicted increases in risks, including flooding.

Some states such as Massachusetts scored well. But in the Ohio Valley the risks were high and the marks were low when it came to planning for increased frequency and severity of floods: West Virginia and Ohio got D’s; Kentucky got an F.

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSource

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSourceThe report found that while the three states have acted to address the current risks to flooding they have done little or nothing in the way of planning and preparedness for the increase in risk that scientists predict. By mid-century the threat of inland flooding is projected to increase by 20 to 25 percent in Ohio and West Virginia if people remain in harm’s way.

In Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia combined, more than 700,000 people live in high-risk areas for flooding. In West Virginia, that means eight percent of the entire state population living in flood-prone places.

Yet the report found that in West Virginia there is no statewide adaptation plan for communities or for sectors such as transportation and health. Further, there was no evidence that the state is implementing any adaptation guidelines or policies in regard to those increased risks for flooding. The report found similar shortcomings in Kentucky and Ohio.

Rising Above

In West Virginia, where June’s flooding killed 23 people and damaged or destroyed more than 5,000 homes and businesses, certified floodplain managers like Charles Baker are taking a hard look at what needs to be done. The steep hills and history of settlements in narrow river valleys naturally puts a lot of people at risk. But Baker said flood-proofing techniques can help some communities become more resilient to flooding.

He pointed out that in many West Virginia communities residents are offered lower flood insurance premiums when they adopt mitigation strategies. Techniques include elevating homes, relocating out of flood hazard areas, or even selling properties to FEMA. Some properties flooded in the past have been purchased and then demolished. The riverbank areas were then left open as parks or green space, which can safely take on high water in the future.

“Not everybody likes permits, not everybody likes regulation,” Baker said, “but we need everybody to realize that when these disasters occur it’s going to save us a lot in trying to rebuild this great state.”

Baker said he thinks West Virginia is on the right path with more than 200 floodplain managers working to lessen the toll from disasters. But he and others cautioned that more could be done and that residents must be mindful of the risks in a warming climate.

LISTEN: Voices Remember High Water

LISTEN: The Flood Next Time: Warming Raises The Risk Of Disaster