News

The Prison Builder’s Dilemma: Economics and Ethics Clash in Eastern Kentucky

By: Benny Becker | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

You are Letcher County, Kentucky. You are rural, mountainous, and in the heart of the central Appalachian coalfields. Your economy is not in good shape. Fox News has called your largest town “the poster child for the war on coal.” You are offered funds to build a new federal prison. It could bring jobs but also brings up troubling moral issues. What do you do?

Call it the prison builder’s dilemma: Letcher County and other rural areas are wrestling with a choice between a potential economic boost and the ethical burden of becoming the nation’s jailers.

Coalfield economies have been hit hard by the industry’s recent decline and eastern Kentucky’s 5th Congressional District has been among the most affected. Today it has the second lowest median household income in the country, and the second-lowest rate of labor force participation. In recent years, a big chunk of the money flowing into the region has come through the Bureau of Prisons. Three federal penitentiaries have been built in the district, and now, money has been set aside to build a fourth— in Letcher County.

“I Don’t Know Anything Better”

Elwood Cornett is a retired educator and preacher of the distinctly Appalachian Old Regular Baptist tradition. More recently, he’s been serving as the head of the Letcher County Planning Commission, and a leader in the effort to bring a federal prison to Letcher County.

These aren’t paid positions, and Cornett said he doesn’t even get reimbursed for his gas money. He said he’s putting his time, money, and effort into this project because he wants to help the people of Letcher County who are having a hard time finding work.

“We’re looking for good paying jobs,” Cornett said, “and I don’t know anything better for the economy than a federal prison.”

After decades of extracting coal from the most accessible and cost-effective seams, central Appalachia is struggling to compete with coalfields in western states and overseas. Plus, the coal market as a whole is struggling to handle increased pressure from cheaper natural gas and federal regulations.

Letcher County is definitely feeling the downturn. The county has lost over 90 percent of its coal industry jobs since 2000. Those are positions that often paid around $70,000 dollars without requiring a college degree, so they’re really hard to replace.

One thing that Letcher County does have going for it is a congressman who chairs the House Appropriations Committee. Rep. Hal Rogers has already worked to have three federal prisons built in his district, and as he told the audience at a recent public forum, it’s likely Letcher County will be soon be home to the his district’s fourth.

“There’ll be about 300 new jobs in this county,” Rogers said, “not to mention…it’s a $444 million dollar construction project.”

The Bureau of Prisons has not yet issued a final decision but the federal budget does include a $444 million allocation. When Rogers asked Attorney General Loretta Lynch about the prison in a hearing she replied, “Those funds are going to build a new prison in Kentucky, and I believe it’s going to be in Letcher County.”

You might find it surprising that the government is building new prisons. After all, the U.S. prison population has been in decline since 2009 and polls show most American voters think it ought to keep shrinking. But after three decades of growth in inmate numbers, 7 years of decline haven’t been enough to solve problems of overcrowding. With over 2.2 million people behind bars, the U.S. has far more prisoners than any other country, topping China by more than a half million, despite having a total population less than one twentieth of China’s.

“Doing More Harm Than Good”

Not everyone agrees that the solution is to build more prisons. Dr. Judah Schept, a professor at Eastern Kentucky University’s School of Justice Studies, says that the problem of overcrowding is deeply rooted in an over reliance on prisons. He holds that the only real solution is to stop putting so many people behind bars, and sees the construction of new prisons as a misguided approach.

“It’s not laughable at all,” said Schept, “because we’re putting very poor people in some very bleak and even violent places. But it’s absurd.”

Schept also takes issue with the idea that a prison can help Letcher County’s economy. Schept cited a 2010 study that compared nearly thirty years of employment rates in counties with prisons to their surrounding areas. The study suggests that prison construction is not a reliable strategy for rural economic development. And when it comes to rural areas like Letcher County that are already struggling, the study did not give reason for hope.

“Our research into employment growth suggests that prisons are doing more harm than good among vulnerable counties,” the authors wrote. Schept said that conclusion lines up with the bulk of what social science research has found about the construction of new prisons.

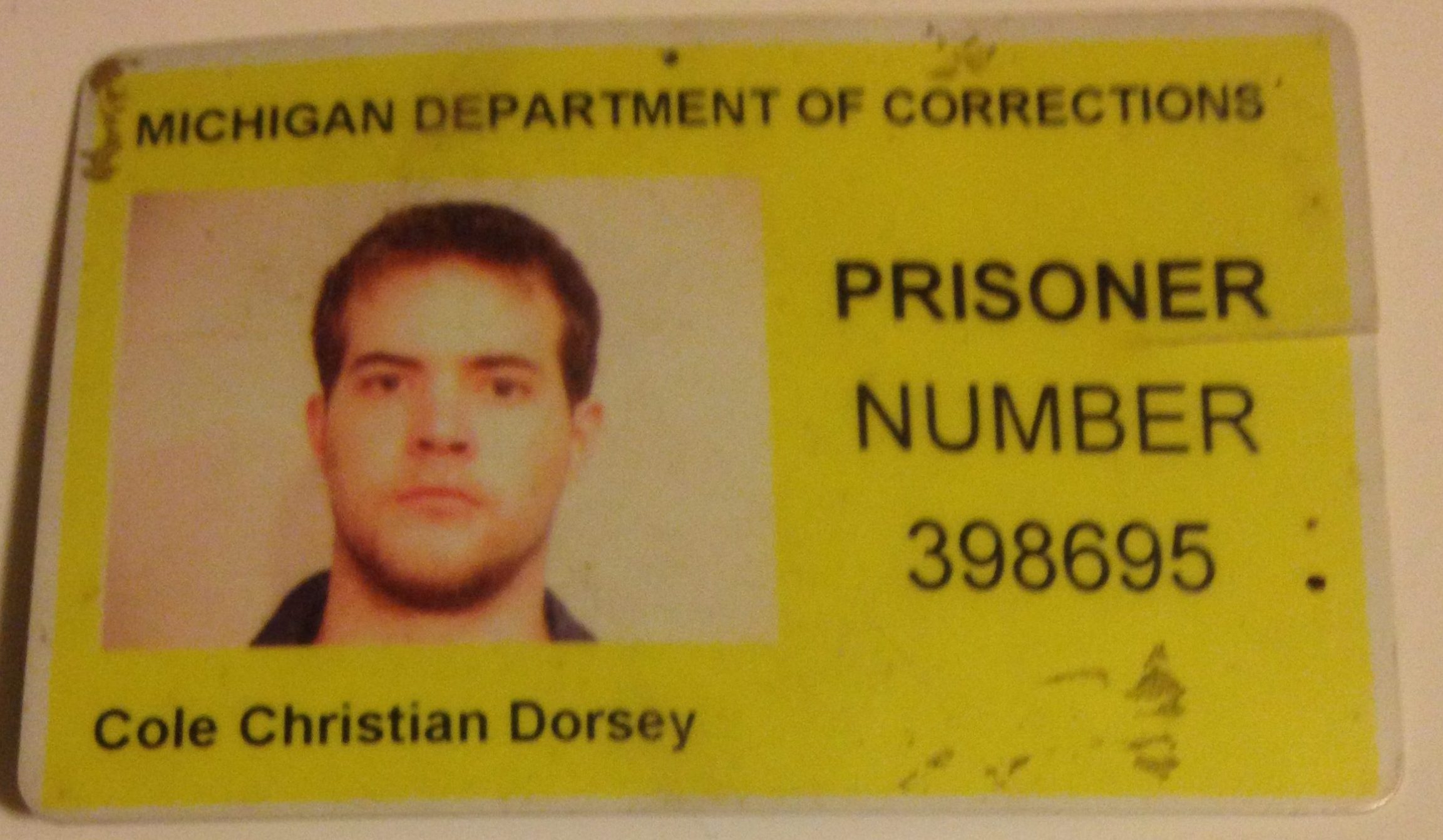

Cole Dorsey has firsthand experience inside prisons. Dorsey says he was incarcerated for starting a riot when he was 13, then was arrested again as a juvenile for heroin use, and then served three years behind bars as an adult for delivering heroin to a police officer.

Dorsey was released in June, 2004, and soon joined a union, which he credits for keeping him away from the habits that got him in trouble. Now, Dorsey is a power line worker and an organizer for the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee. Dorsey said prisons have become an easy solution for too many of society’s issues.

“Because we don’t have jobs and because we don’t have other options for psychiatric or substance abuse issues,” Dorsey said, “our remedy is locking people up, which doesn’t work.”

A Moral Question

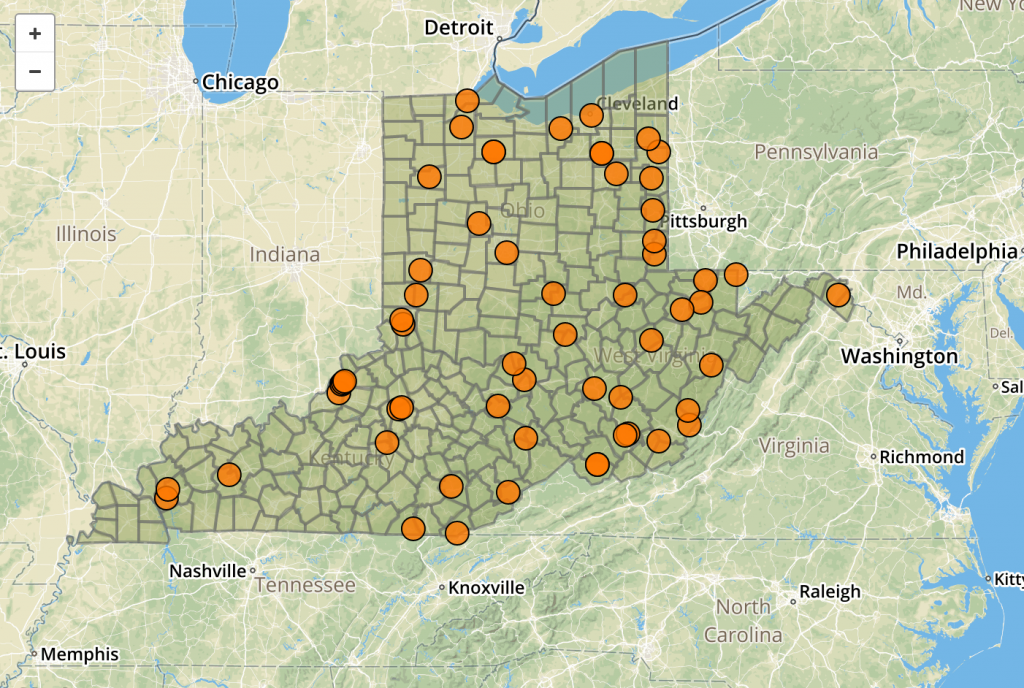

Prisons aren’t exactly new in this neck of the woods. There are fifteen prisons within one-hundred miles of Letcher County. WMMT, the community radio station where I work, is located in Letcher County’s largest town (Whitesburg, population 2,139). Each week the station airs programming targeted toward listeners who are locked up.

Every Monday night while “Hip-Hop from the Hilltops” is on the air, volunteers take calls from people who have loved ones incarcerated in the area. There’s a toll-free number available, and callers get to record a “shout-out” that gets broadcast right after the hip-hop. The program, “Calls from Home,” helps prisoners stay connected to their friends and families by offering a free alternative to notoriously expensive prison phone services.

In a typical call, a child’s voice came through the phone: “Hello?”

An older voice coached the child: “Talk! Talk! It’s a shout-out.”

“Oh,” the child continued, “Hi Lucky! I love you, but I want to know when you’re gonna get out!”

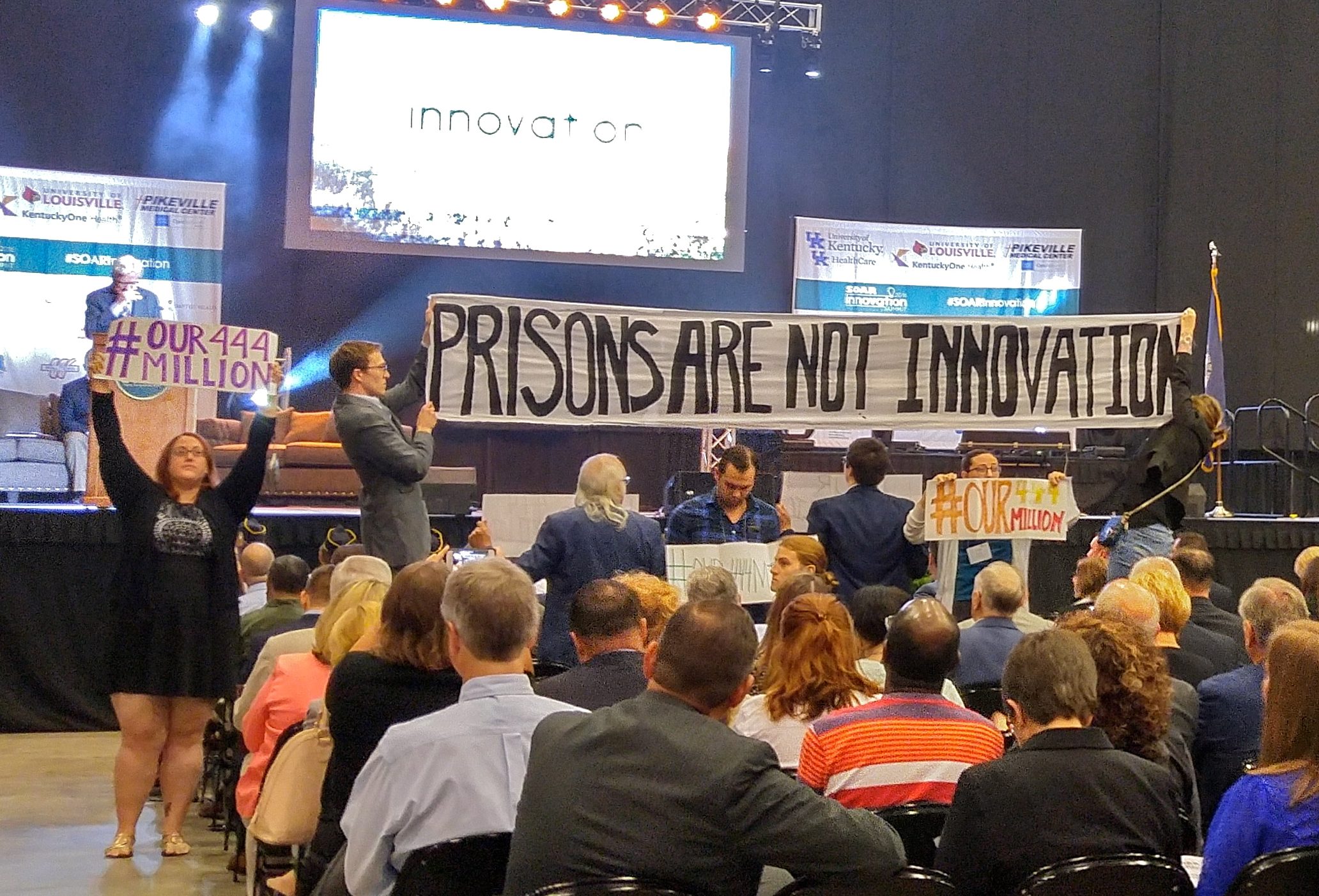

Tarence Ray is one of the volunteers behind “Calls from Home.” He’s also involved in a group called the Letcher Governance Project, which has been a leading local voice arguing against building a new prison. The group made headlines in May, when Ray and others held up signs protesting the prison while Rep. Rogers addressed a large crowd and live television audience at a high-profile regional summit.

Ray said that members of the Letcher Governance project have different reasons for objecting the plan to build a prison. Ray is skeptical that the prison will have a positive impact on the economy based on the lackluster effect he’s seen in McCreary, Martin, and Clay Counties. Those three nearby counties already have federal prisons.

On the moral front, Ray described construction of a new prison as a part of a larger system that exploits poor people, and especially people of color. His critique of the prison system is similar to that outlined by civil rights lawyer Michelle Alexander in her book “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness.”

Alexander’s book drew upon the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s statement that the south’s Jim Crow system told the poor white man “that no matter how bad off he was, at least he was a white man, better than the black man.”

Ray said he hears echoes of what King described in the prison debate today. He sees Letcher County as the latest instance of an old pattern in which working-class white people are told they have no choice but to support the oppression of black people.

As Ray described the line of reasoning, “Jobs are gone, coal is gone, what else are you going to do?” He called it “a really perfect encapsulation of what racism in 2016 looks like.”

The Letcher Governance Project launched a social media campaign with the hashtag “#our444million” to gather other ideas for how that amount of money could be spent. Ideas posted on Twitter and Facebook include expanding treatment options to combat the region’s opioid epidemic, supporting local agriculture, and investing in expanded internet access.

But as Elwood Cornett and other prison supporters have pointed out there’s only one idea that already has $444 million allocated for Letcher County.

Unless the Bureau of Prisons has a sudden change of heart or runs into issues buying the necessary land, it seems likely that this prison will be built. Either way, the people of central Appalachia will continue to debate what role prisons should play in the region’s future.