News

White Stuff: Amid Election Rancor, Writers Reassess The White Working Class

By: Jeff Young | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

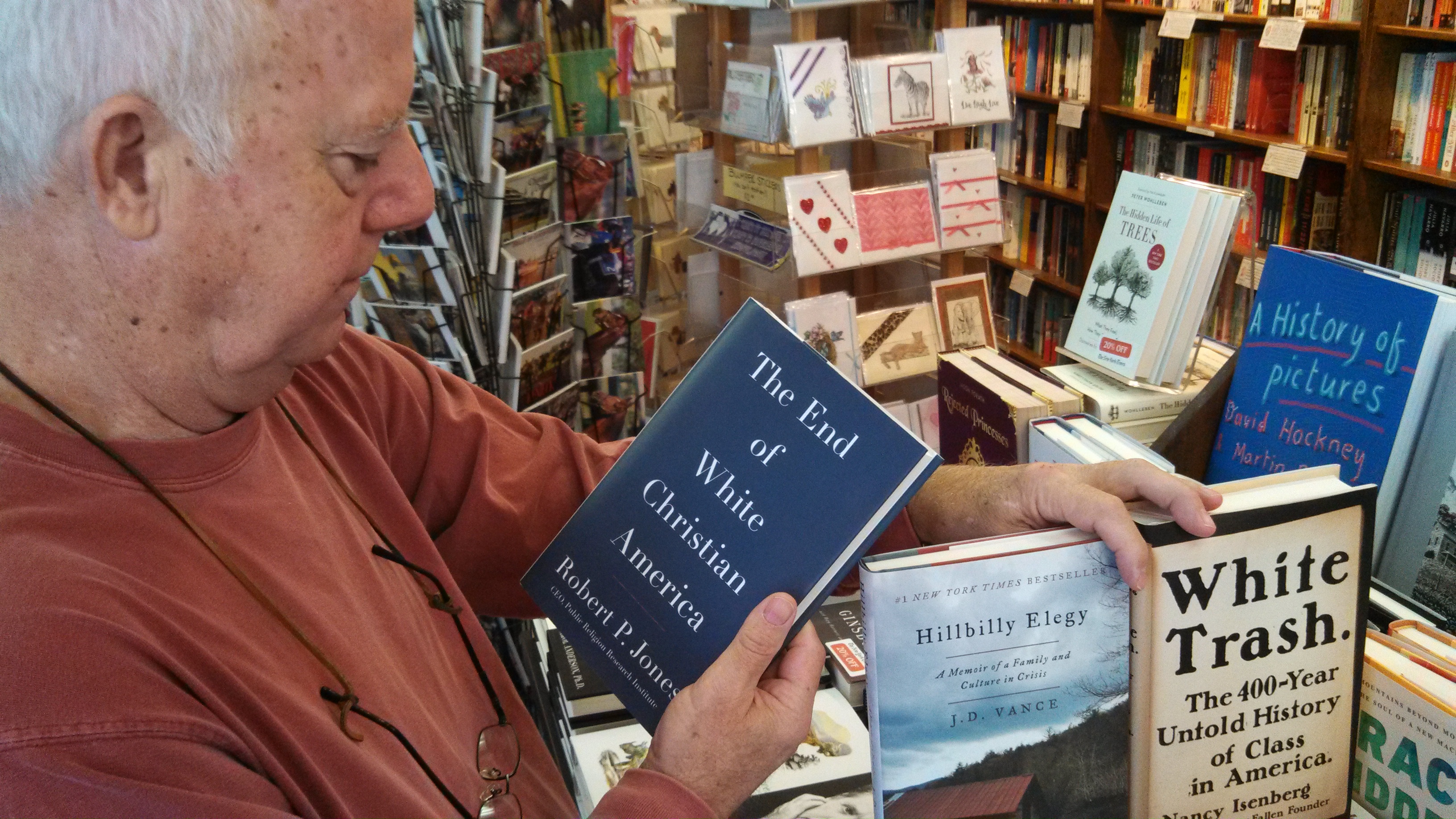

One look at the recent arrivals shelf at Carmichael’s Books, in Louisville, and I knew something was up. Titles like “White Rage,” “White Trash,” and “The End of White Christian America” were piling up.

“And then this has been the surprise,” Carmichael’s co-owner Michael Boggs said, picking up another hardcover. “This actually hit the Times bestseller list: ‘Hillbilly Elegy’ by J.D. Vance.”

Boggs has been in the book business nearly four decades, so he’s seen publishing trends come and go. This trend is built on something that hits close to home.

“I think we’re talking about white working class disappointment at what their lot has been,” he said. “Being ignored or being ridiculed, really.”

Many writers are taking a fresh — and some would say overdue — look at these often overlooked voters in this, their electoral season of discontent. I spoke with three authors who take very different approaches — statistical, personal, and historical — to explore why the white working class has such a dark outlook on the country and their future in it.

The End of White Christian America

Robert P. Jones of the Public Religion Research Institute uses demographics to explain what he calls “The End of White Christian America.” That’s the title of Jones’s book about the recent decline of the country’s dominant cultural force.

“If we go back just two election cycles ago, to 2008, when Barack Obama was first running for president, the country was a solidly majority white Christian country: 54 percent of the country identified as white and Christian in 2008,” Jones said. “That number today, from our latest surveys, is just 43 percent.”

Jones said that has brought a sense of loss, anxiety and fear that’s seeping into public debate on a range of issues, and Donald Trump has seized on that.

“Donald Trump has essentially converted ‘values voters’ into what I call ‘nostalgia voters,’” Jones explained. “His slogan, ‘Make America Great Again,’ that last word, ‘again,’ really does hearken back to a time when white Christian churches and people had much more power in the culture than they have today.”

Jones said polarization along class and race lines has decreased the person-to-person conversation that can happen with someone who doesn’t look like you. Churches, which could provide common ground, remain highly segregated.

“When Martin Luther King, Jr., said that 11 o’clock on a Sunday morning is the most segregated hour in American public life, well that is still largely true,” Jones said, citing a statistic that 90 percent of churches remain mono-racial. An analysis of social networks also shows little diversity.

“For the average white person in America, their close personal social friendships are 93 percent white, and three-quarters of white people have no people of color in their close friendship groups,” Jones said. “So when it comes to these thorny issues of ‘black lives matter’ and police violence, not enough people have opportunity to have conversations across these divides.”

From “The End of White Christian America”

Robert Jones begins “The End of White Christian America” with this “obituary notice” for WCA.

After a long life spanning nearly two hundred and forty years, White Christian America — a prominent cultural force in the nation’s history — has died. Although examiners have not been able to pinpoint the exact time of death, the best evidence suggests that WCA finally succumbed in the latter part of the first decade of the 21st Century. The cause of death was determined to be a combination of environmental and internal factors — complications stemming from major demographic changes in the country, along with religious disaffiliation as many of its younger members began to doubt WCA’s continued relevance.

Among WCA’s many notable achievements was its service to the nation as a cultural touchstone during most of its life. It provided a shared aesthetic, a historical framework, and a moral vocabulary. During its long life, WCA also produced a dizzying array of institutions, from churches to hospitals, social service organizations, and civic organizations.

Late in its life, WCA struggled to adequately address issues such as lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender rights, which were of particular importance to its younger members, as well as to younger Americans overall.

WCA is survived by two principal branches of descendants: a mainline Protestant family residing in the Northeast and upper Midwest and an evangelical Protestant family living mostly in the South. Plans for a public memorial service have not been announced.

Hillbilly Elegy

Where Jones leans on statistics, J.D. Vance’s “Hillbilly Elegy” draws on his personal experience in small town Ohio (Middletown, near Dayton) and Kentucky (Jackson, in Eastern Kentucky). Subtitled, “A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis,” it’s a searing account of a childhood amid the chaos of his mother’s addiction and a family often torn by abuse and financial insecurity.

Vance recounts a parade of boyfriends and stepdads as his mother became more erratic and abusive. At one point as a teenager, his mother demanded clean urine from him so that she could pass a workplace drug test.

Eventually, Vance goes to live with his gun-toting grandmother, who, despite her creative cursing and occasional violence, provides a stable and loving home. Vance became a serious student, later joined the Marines, and wound up studying law at Yale.

It’s an “up-by-the-bootstraps” story but one told at the expense of unearthing some painful family history.

“It definitely was difficult to write about it, but I was motivated to write it because I think that people did not appreciate the scope and scale of the challenges that exist in these families,” Vance said. “And if I wanted to show that, there was no better way than to open up my own life, my own family, and say, ‘This is what it looks like when you’re really struggling to get ahead.’”

Vance said the combination of economic stagnation and a deadly opioid addiction crisis has darkened the mood in the Midwest and Appalachia, and has many rural Americans voting out of a sense of despair.

“They don’t believe anymore in the promise of the American dream, they don’t believe that hard work can connect them to better opportunities, because no matter what they do they just don’t believe that they are going to have a better life,” he said. “That feeling isn’t made up, it doesn’t come from nowhere.”

Vance’s memoir has struck a chord. He’s on the bestseller list and appears in opinion pages and on cable news shows as a sort of guide to help coastal elites understand Middle American woes.

But while his personal story is compelling, Vance’s diagnosis of social problems has drawn criticism for tilting toward a “blame-the-victim” mentality.

Vance describes himself as a conservative — although he criticizes some conservative positions on poverty — and attempts to thread the needle between liberal ideas about public assistance and conservative emphasis on personal responsibility.

He writes: “I believe we hillbillies are the toughest goddamned people on this earth. But are we tough enough to look ourselves in the mirror and admit that our conduct harms our children?”

Does Vance view the problems he describes as personal or structural? And what he would like to see happen if people in the region took a “hard look” at themselves?

“Well I think it’s both, it’s hard to tease out the personal from the structural,” he said. “I’d like us to think about how the ways we conduct ourselves can be detrimental to our children. All these things matter. And also that policymakers know they can put their thumb on the scales for these people, that it’s not hopeless.”

From “Hillbilly Elegy”

Some samples from “Hillbilly Elegy” by J.D. Vance.

“This was my world: a world of truly irrational behavior. We spend our way into the poorhouse … we spend to pretend we’re upper-class … we know we shouldn’t spend like this. Sometimes we beat ourselves up over it, but we do it anyway.

“Our homes are a chaotic mess. We scream and yell at each other … a bad day is when the neighbors call the police to stop the drama.

“We don’t study as children and we don’t make our kids study when we’re parents … We choose not to work when we should be looking for jobs … We talk about the value of hard work but tell ourselves that the reason we’re not working is some perceived unfairness: Obama shut down the coal mines, or all the jobs went to the Chinese.

“These are the lies we tell ourselves to solve the cognitive dissonance — the broken connection between the world we see and the values we preach.”

“There is a cultural movement in the white working class to blame problems on society or the government, and that movement gains adherents by the day … What separates the successful from the unsuccessful are the expectations that they had for their own lives. Yet the message of the right is increasingly: It’s not your fault that you’re a loser; it’s the government’s fault.”

White Trash: A History of Class in America

Louisiana State University historian Nancy Isenberg cautions that Vance’s personal tale, though compelling, places too much emphasis on individual choice.

“Blaming it on family dysfunction, blaming it on drug addiction, misses that these are rooted in economic dislocation,” she said.

Isenberg’s book, “White Trash,” is subtitled: “The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America.” She argues that despite our national myth of a land of opportunity borne from the American Revolution, we carried British notions of class into the American experiment.

Isenberg covers a lot of ground to make her case, but the most compelling thread traces the language used to describe the poor, and how those words work over and over to excuse the oppression of “waste people.”

She documents terms such as crackers, sand-hillers, mudsills, swamp-dwellers and clay-eaters, (all refer to the marginal lands the people were forced to use) right up to the title slur, white trash. All were used to make poor working people of the rural south and Appalachia seem like a different breed: people whose self-destructive behavior made them less than fully American.

“We begin to see this focus on how they are a group of people that have so many defects that somehow they can never be assimilated into normal society,” Isenberg said. “This is how Americans can ignore class. If you claim that no education, no charity can uplift these people because of their derelict ways, then you can essentially write them off.”

Isenberg sees echoes of this in many media depictions of the Ohio Valley and Appalachia region, and attempts to explain Trump’s appeal. She singled out the mean-spirited reporting of National Review writer Kevin Williamson, whose view of a “Big White Ghetto” paints a freak-show Appalachia with little mention of the exploitative industrial practices that have defined Appalachian history.

“We have to realize that class has a geography,” Isenberg said. “The place you’re born, your neighborhood, family, all determine your advantage.”

She cited a statistic that upper middle-class parents pass on 50 percent of their wealth to their children.

“What that means is that we are imitating old-world aristocracies where the most fundamental determinant of success was wealth and privilege from parents and ancestors,” she said. “Hard work is not enough to get ahead. That’s one thing Americans do not want to talk about.”

From “White Trash”

Some samples from Nancy Isenberg’s “White Trash.”

“Dirt poor southerners living on the margins of plantation society became even more repugnant as “sandhillers” and pathetic, self destructive “clay eaters.” It was at this moment that they acquired the most enduring insult of all: “poor white trash.”

The southern poor were not just lazy vagrants; now they were odd specimens in a collector’s cabinet of curiosities, a disabled breed. The popular vocabulary had become ominous. No longer were white trash simply freaks of nature on the fringe of society: they were now congenitally deficient, a withered branch of the American family tree.

“The problem was not: “No one knows what to do with him.” It was this: “No one wants to see him as he really is: one of us, an American.” “A corps of pundits exist whose fear of the lower classes has led them to assert that the unbred perverse are crippling and corrupting American society. They deny that the nation’s economic structure has a causal relationship with the social phenomena they highlight. They deny history. If they did not they would recognize that the most powerful engines of the U.S. economy—slave owning planters and land speculators in the past; banks, tax policy and corporate giants today—bear considerable responsibility for the lasting effects on white trash and on the working poor generally. The sad fact is, if we have no class analysis, then we will continue to be shocked at the numbers of waste people who inhabit what self-anointed patriots have styled the “greatest civilization in the history of the world.”

Election Focus But No Finale

J.D. Vance told me that his book’s success is largely driven by readers on the country’s coasts who are puzzled by Trump’s appeal in the Heartland.

“It’s unfortunate that people just don’t know these areas where Trump has support,” he said. “They think of these supporters as foreign exotic animals and they’re trying to understand them.”

The election has clearly put the condition of the white working class on the nation’s radar. The question now is whether anything will change.

“I am skeptical about a long-term, serious examination,” Isenberg said. “I’m not surprised that class is again at the forefront, but it is easier to retreat to the myths of American democracy and American ideals.”

Jones sees no quick solution to the deep divisions his book identifies.

“We’ve crossed a threshold fundamental to so many white Christians and their sense of what the country was,” he said. “No matter what the issue, the heat and apocalyptic rhetoric outstrip what we’re talking about.”

The white working class issues may be driving this rancorous election, but they certainly won’t go away on Election Day.