News

Trumped: Coal’s Collapse, Economic Anxiety Motivated Ohio Valley Voters

By: Jeff Young | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

The electoral map of Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia is a sea of red with a few islands of blue. Of the 263 counties in the three states only nine went for Hillary Clinton, most of them around the region’s cities.

The Ohio Valley ReSource looked to voters and voting data to learn more about what motivated Donald Trump’s supporters and what they hope he will do as president.

“More than Obama did!” Judy Collier said from a grocery story parking lot in Whitesburg, Kentucky. “We need jobs.”

“I don’t think Trump is some savior,” Athens County, Ohio, native Rebecca Keller said. “But he is somebody with a different perspective.”

“I will keep my fingers crossed that he can effect some real change in this country,” Jack Rose said in Wheeling, West Virginia.

The county-by-county vote results also tell a story when matched against some of the region’s key economic and social indicators. Some insights and some questions arise about what Trump voters want.

Coal’s Collapse

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSource

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSourceOne obvious factor was the anxiety over the collapse of the region’s coal industry.

“Our coal jobs are gone here in eastern Kentucky,” Collier said. She lives in Eolia in Letcher County, which has seen a sharp drop in mine production and employment.

David Boggs of nearby Cumberland echoed the hope that Trump will reverse the decline.

“He’ll put the coal business back together and straighten this country up a little bit, maybe.”

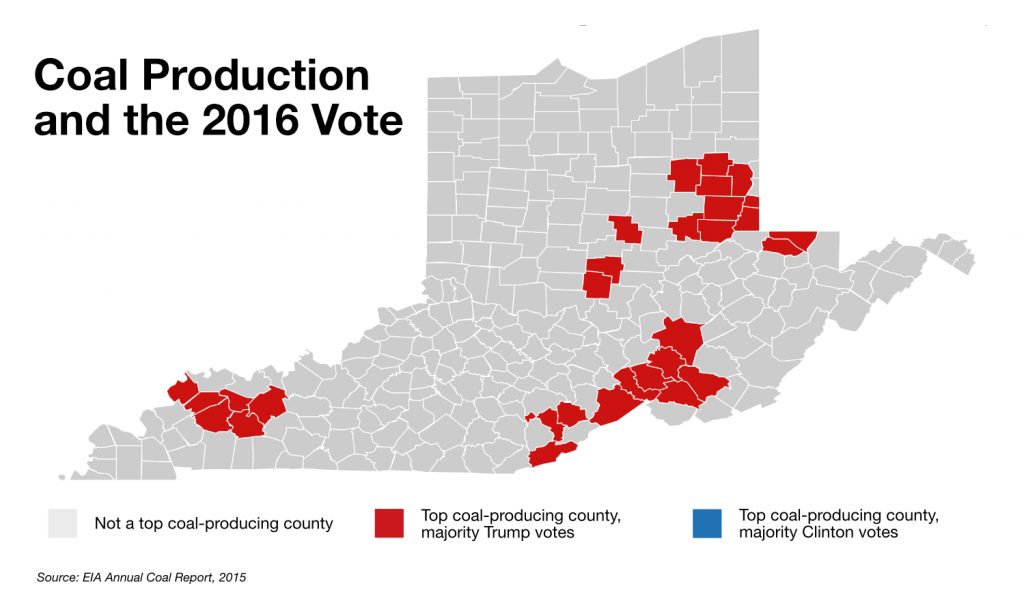

Resource data reporter Alexandra Kanik looked at the votes for Clinton and Trump in the counties in the three-state region that produce the most coal. (Her results can be seen in the accompanying maps.)

“The top coal producing counties in the region had two, three, sometimes six times the support for Trump over Clinton,” Kanik found.

Trump seized on coal’s demise and pinned the blame on federal regulations. West Virginia University history professor William Hal Gorby said that fits a long pattern in regional politics.

“Rolling back environmental regulations, what’s called the overreach of EPA, it’s sometimes referred to as the ‘war on coal,’” Gorby said. “That language has had a lot of support, of course, before Trump was running for president.”

The “war on coal” still makes for politically potent rhetoric. However, it does not match well with facts. Executives at electric utilities say their move away from coal has more to do with economics than environmental regulation — natural gas is just cheaper. And since Election Day some mining industry supporters have walked back their promises of a coal comeback.

Rust Belt Blues

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSource

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSourceTrump supporters also hope manufacturing jobs might return.

Electrical contractor Jack Rose of Wheeling once worked in the steel industry that sustained the city for decades.

“I saw the industry decimated by the wealthy who wanted to maximize profits,” he said. “You see jobs outsourced to Mexico, Canada, China, everywhere but here.”

Martin Dofka, an airplane mechanic in Wheeling, also worked in the steel mills before they shut down. “I believe there should be tariffs on imports if those companies don’t meet standards they’d face in the U.S.,” he said. “It is unfair labor that’s created the Rust Belt.”

While free trade helped consumers and some companies here, the Ohio Valley’s heavy manufacturing base clearly came out on the losing end of many trade deals. Many manufacturing and mining communities fell into economic distress.

What a Trump administration might do about that is an open question. On the campaign trail, Trump pledged to take a tougher stance with trading partners and to renegotiate or scrap some free trade deals. One of those deals, the pending Trans-Pacific Partnership, now appears to be dead.

However, a recent incident in the region raises questions about how well Trump’s rhetoric matches reality when it comes to manufacturing and trade. On November 17 the president-elect used his Twitter account to claim credit for preventing Ford from moving a Kentucky plant to Mexico.

“I worked hard with Bill Ford to keep the Lincoln plant in Kentucky,” Trump tweeted.

But Ford made clear that the plant, which makes a Lincoln-branded SUV, was not in consideration for a move to Mexico and that no jobs at the plant were in danger. Rather, the company was considering an assembly line switch to another model of SUV (the Ford Escape).

Poverty and the Polls

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSource

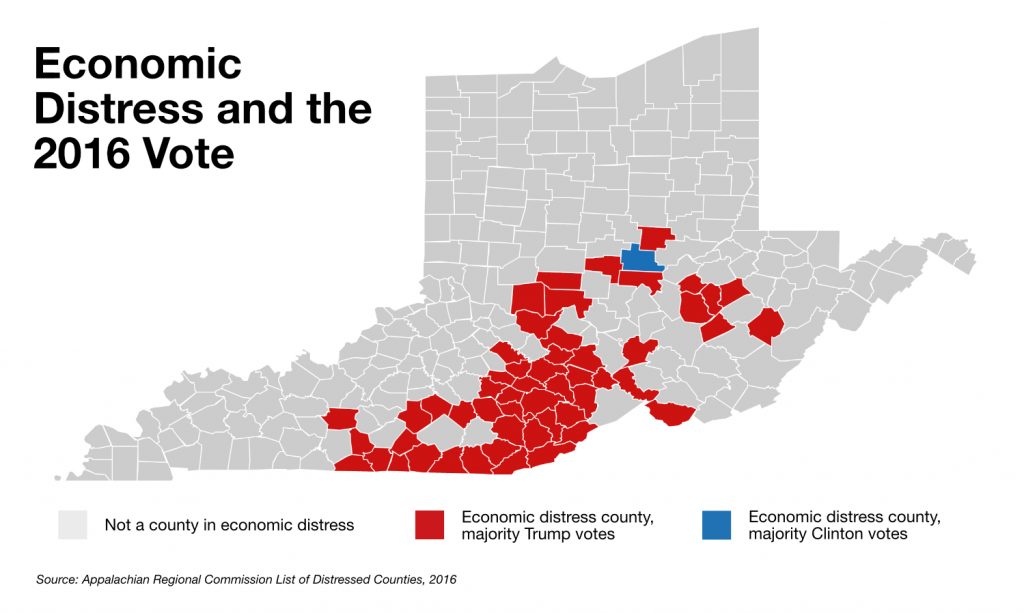

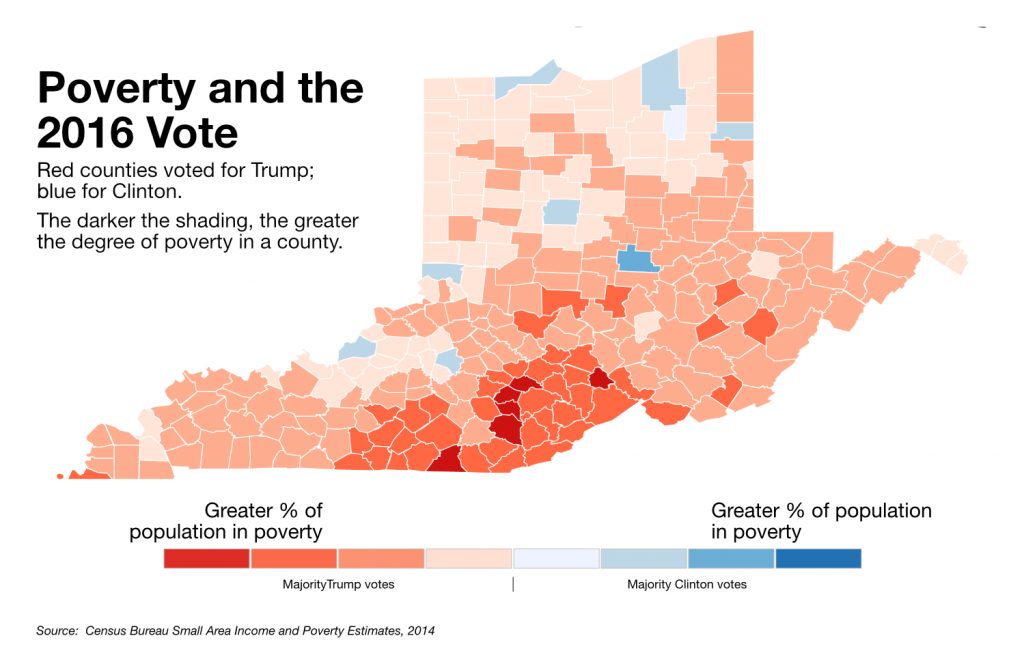

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSourceReSource reporter Kanik’s analysis shows several counties in the region with the worst poverty also had the greatest turnout for Trump.

“Martin County, with some of the highest poverty in Kentucky, had 10 times the vote for Trump,” she said. “In fact, no county in our region with greater than 30 percent poverty went blue.”

The Appalachian Regional Commission classifies 54 counties in the three states as economically distressed. All but one — Athens County, Ohio — went for Trump.

Democratic positions on taxes and government services traditionally favor folks with low incomes, giving rise to the argument that many people in the region are voting against their own economic interests.

But historian Gorby argued that it’s not that simple. Democrats, he said, long ago drifted from the New Deal coalition platform that appealed to many working people and the poor.

“They moved away from core issues of economic security that really matter a lot to ordinary working people and particularly rural voters,” Gorby said. “It’s left a lot of people in the Rust Belt and Appalachia feeling neglected.”

The Healthy Choice?

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSource

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSourceHealth care was also an issue for some Trump voters.

“We need medical care,” Judy Collier said. “More than Obamacare — cheaper medicine.”

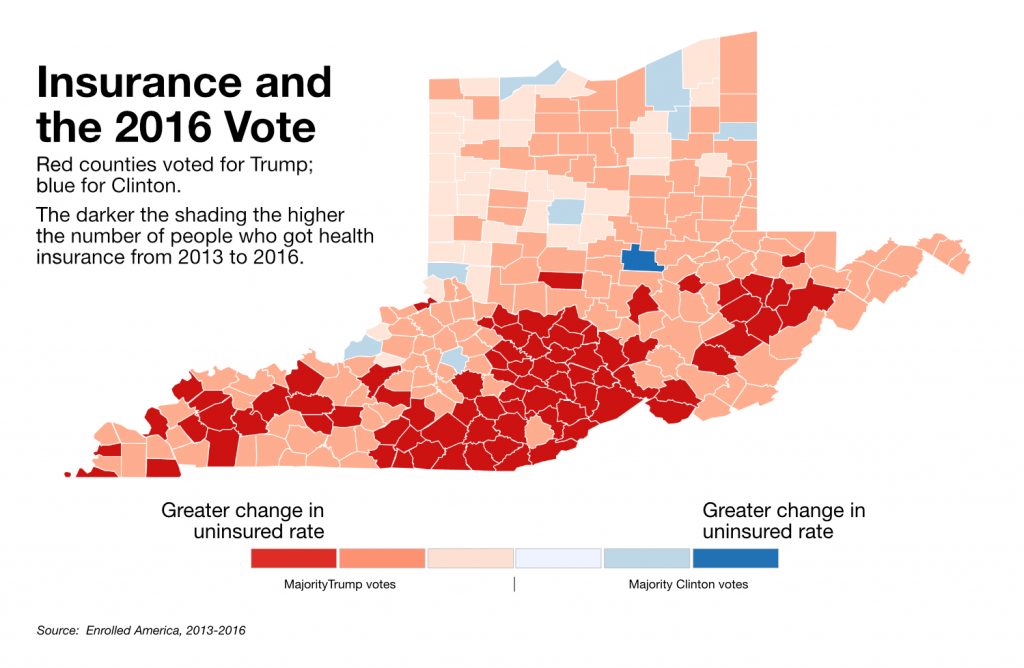

This is an issue where the vote and the data tell different stories. Kanik noted that as recently as 2013, Kentucky and West Virginia had uninsured rates of 20 percent or higher. Both states made tremendous progress under the Affordable Care Act.

“By 2016, after both states expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, we saw rates much closer to 5 or 10 percent,” she said.

Yet only two counties in those two states went blue. Most voted for the candidate who pledged to repeal the Act.

“It’s an interesting phenomenon,” said Simon Haeder, a professor at WVU’s John D. Rockefeller IV School of Policy and Politics, where he focuses on health care.

Haeder said that his research shows that many people strongly support most elements of the Affordable Care Act. But when asked about “Obamacare,” that support plummets.

“Most members of the public have little idea of what the Affordable Care Act is or what it does,” he said. He blamed misinformation from the media and the major parties.

“One of the major parties certainly has every incentive to distort what it does,” Haeder said. “And the other party has done a poor job explaining how people benefit.”

ReSource reporters Benny Becker, Glynis Board, Nicole Erwin, and Aaron Payne contributed to this story.