News

Growing Concerns: Trump’s Immigration Rhetoric Sows Anxiety In Agriculture

By: Nicole Erwin | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

On Nelson Key Road in Murray, Kentucky, lies a 30-acre tobacco farm and there sits the road’s namesake, Nelson Key himself. He’s just at the end of this year’s harvest, which was brought in with the help of migrant workers.

“I used American workers up until 1991 then I went to the migrant workers and I’ve had them ever since,” he explained.

Over the years Key found it harder to hire domestic labor despite offering pay above minimum wage. Migrant workers now fill the gap. He uses the immigration service’s H-2A program for temporary agricultural workers. Key has to show that he tried to hire locally before he’s eligible to hire foreign labor for seasonal work.

That’s how he found Jose Humanez, a 33-year-old from Nayarit, Mexico. He grew up around tobacco and has worked for Key for 11 years. He said the H-2A process wasn’t too complicated.

“It’s not that hard but it takes a bit of work,” Humanez said. His cousin who had also worked in U.S. agriculture told him about the opportunity.

The H-2A program requires producers to provide adequate housing, workman’s comp insurance, transportation from home to the farm and a road-ready vehicle for independent use.

Humanez is satisfied with the program and said he believes it protects his rights as a worker. He speculated that many Mexicans who come here illegally either don’t have access to the information about work programs or are just desperate.

“There are places in Mexico that this information and paperwork simply doesn’t get to them,” he said. “They don’t know that it exists or they don’t have access to it, one way or another.”

Humanez is vaguely familiar with Donald Trump, and said he isn’t afraid of his threats to build a wall or deport immigrants because he is in the country legally. But millions of other workers on farms and in stockyards and processing facilities are not. Researchers say the sort of mass deportation Trump talked about could wreak havoc on the country’s food system.

Labor Shortages

“If we do see a policy of mass deportation it would have really, really significant negative effects,” according to Philip Wolgin, director of immigration policy at the Center for American Progress, a liberal policy and research advocacy group based in Washington, D.C..

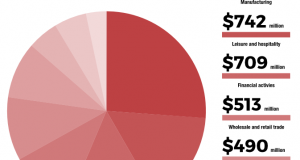

CAP reports that the removal of 11 million undocumented workers living in the U.S. could reduce the gross domestic product by $434 billion, on average annually, wiping away anywhere between 8.5 percent and 21 percent of the country’s agriculture industry.

Trump’s immigration reform plan is unclear, said Wolgin, but he thinks dramatic change is likely via some mix of policies that would result in forcing unauthorized immigrants out of the country.

“Everything from making life as difficult as possible for them, random raids that drive terror through immigrant communities, have more employment verification penalties on working without status, and that sort of thing,” Wolgin said.

The president-elect has indicated in recent statements that he might be backing away from campaign pledges to deport 11 million people. Wolgin said it’s “a bit dangerous” to assume that Trump might not follow through on his commitments to mass deportation and building a wall.

“Particularly because of who he has advising him on immigration,” Wolgin said. He pointed to Trump’s nominee for Attorney General, Sen. Jeff Sessions, and Trump adviser Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach, as two of the most noted critics of immigration.

Immigration reform doesn’t only affect the migrant community, Wolgin said.

“For example, you’ve also got people that package those crops and people that drive them to where they will be sold and then stores that sell them,” he explained. “All of those people that rely on farm workers end up seeing their own economic positions weakened.”

Food Security

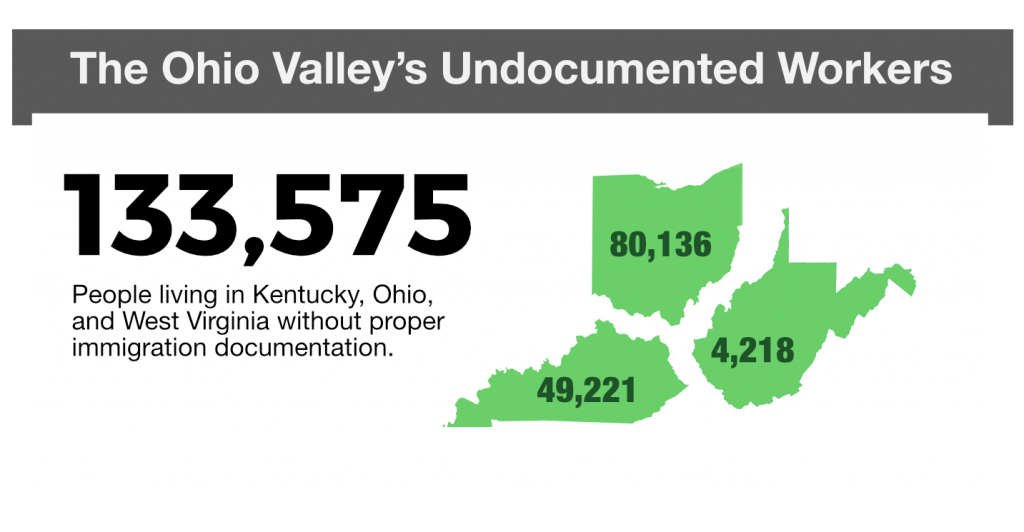

Each state would feel different impacts from immigration changes. A 2012 report by the Ohio Latino Affairs Commission estimates 70 percent of the state’s migrant agricultural workforce is undocumented. Kentucky and West Virginia could feel the impact in increased food costs. Lisa Meierotto, a cultural and environmental anthropologist at Boise State University, said that brings a threat to food security.

“Food security means having the ability to access nutritional food on a regular basis,” Meierotto said. “So when we talk about food security here, we’re not talking about famines and starvation. We are really talking about the availability of nutritional food.”

Meierotto said that if immigration changes reduce farm labor it’s also a reasonable assumption that the cost of those food items would go up. What people have to pay as a percentage of their their household expenditures for food would also increase, creating “a negative experience for a lot of working families,” Meierotto said.

She said it is important to consider that many of the migrant workers here in the U.S. are also members of working families that now permanently reside in the U.S.

A study by the USDA Economic Research Service found that three-quarters of crop farm workers do not migrate broadly. Instead they work within 75 miles of their homes.

Meierotto attributes this change to the “prevention through deterrence” policy implemented in the early ’90s, which greatly stepped up patrol deployment and barriers along the U.S/Mexico border. The result was a transition in our farm labor.

Most of the migrant labor that Trump has threatened to deport aren’t actually migrant at all anymore, she argued, but rather part of “mixed status” homes, where parents are often undocumented and children were born in the U.S.

Studies by Meierotto and others show that immigration policy changes from decades ago had unintended consequences that are still felt today. She said the “draconian immigration reform” implied by Trump’s rhetoric could have serious consequences for all families, migrant and domestic.

National Security

A lack of access to farm labor could also lead to import dependency, according to Bill Crispin, an agricultural attorney in Gainesville, Florida. He recently wrote an article for the December issue of The Ag Magazine to bring attention to the issue.

“Domestic food production is a national security issue,” Crispin said. “The Farm Bill used to be called the Food Security Act, or had the words of national security in there, and then I think the globalization of agriculture, [trade] opened up through NAFTA, has maybe softened an underlying premise of making sure we have adequate resources to have a sustainable domestic food production.”

When you start importing more food products, Crispin explained, food safety issues become more prominent. “Whether it’s listeria, or salmonella, offshore growing facilities don’t have the same sanitation regulations the U.S. has,” Crispin said.

If there are mass deportations, Crispin said the quandary then becomes sourcing the other labor.

“The argument that by allowing immigrants to do work takes away a job from a citizen hasn’t played out in the reality of a typical farm operation,” Crispin said. “Many farmers have attempted to source labor locally and it is hard if not impossible to find a replacement for that labor.”

Even though farm work is classified as “unskilled” labor, Crispin argued that the term is inaccurate. He said that many have developed techniques that, for example, “enable a worker to fill a bucket of tomatoes efficiently so that the farmer gets the crop out timely and the worker is able to earn a wage,” he said.

Chilling Effect

Georgia has shown what can happen to farm labor when immigration policies change suddenly. In 2011 the state implemented stricter policies requiring growers to adhere to additional registration. Charles Hall, Executive Director of the Georgia Growers Association, said rumors circulated among migrant workers and the flow of labor stopped. This “chilling effect” caused a 40 percent decline in labor according to the Georgia Growers Association, dropping crop revenues $140 million, with a multiplier effect of $390 million lost in economic activity.

Hall said what any actual policy from the incoming Trump administration might be is pure speculation at this point. Unfortunately, he said the heated rhetoric from the campaign could have its own effect, which is what he saw happen in his state in 2011.

“We had workers tell us they had heard there were barricades at the border between Georgia and Florida and that is why they didn’t come to Georgia to work,” he said. “So it’s really difficult to know what is going to happen until we have more on the table.”

Hall said more producers in Georgia are using the H-2A program, as Nelson Key did for his Kentucky tobacco farm. But Hall said the program has some drawbacks.

“As we have seen more of our growers increase in reliance on H-2A, we have not seen an increase in staff at the U.S. Department of Labor,” to process requests under the program, he said.

This has caused a delay in the arrival of immigrant workers in an industry where time is critical. Hall said growers are set back by the smallest problems, such as an error on an application where a grower hasn’t capitalized a name. Until recently, Hall said, all paperwork was sent via mail — snail mail. Only recently were electronic services added.

As the new administration takes office, he said, any immigration reform has to “go hand in hand with a guest worker program.”

A Trump Ag Adviser

Kentucky Commissioner of Agriculture Ryan Quarles is also on Trump’s Agriculture Advisory Council. He said his main role is to advocate for the producers, and they have been clear they want change.

“The Ag community has been aggressively advocating reforming the H2A program for well over a decade,” Quarles said. “The program is inflexible, it has tremendous administrative burden, and in some cases has caused shortages in the labor force because the program is too cumbersome.”

Quarles said Trump’s Advisory Committee last met the day before the end of the presidential elections, and the group has submitted a document to the president-elect on a number of issues, including H-2A reform.

Others interviewed for this story agree H-2A reform is a must. But millions of the workers in our food system still face a lot of uncertainty until the president-elect clarifies his plans on immigration.