News

Closing Clinics: Abortion Rights Increasingly Out Of Reach

By: Mary Meehan | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

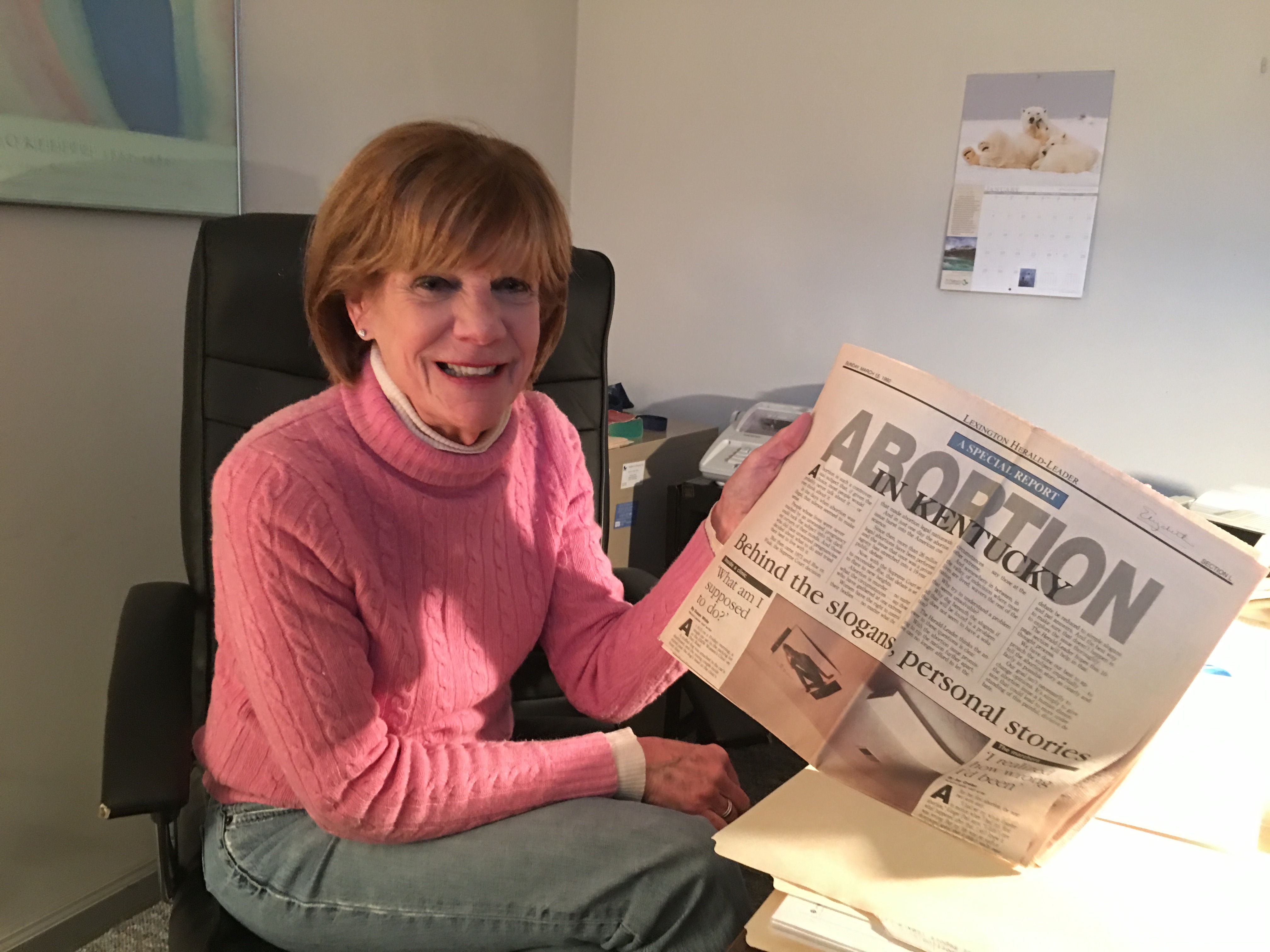

Dona Wells walked through what’s left of the EMW Women’s Clinic in Lexington, Kentucky. Boxes fill what use to be offices. Sterilized medical supplies are in disarray. A light flickers on and off in the back hallway. She doesn’t see a point in fixing it. At 75, she still runs 25 miles a week, but Wells is tired.

“I was going to retire anyway, probably this year,” she said. But I wanted to do it on my terms, not Gov. Bevin’s terms.”

That would be Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin, who recently signed two bills into law further restricting abortion services: one requiring an ultrasound as part of abortions and another prohibiting the procedure after 20 weeks of pregnancy. The final straw for Wells came in the form of a new license requirement from the state. Wells has been battling restrictive rules for most of the clinic’s 28 years, but the battle is over now. She’s closing the clinic.

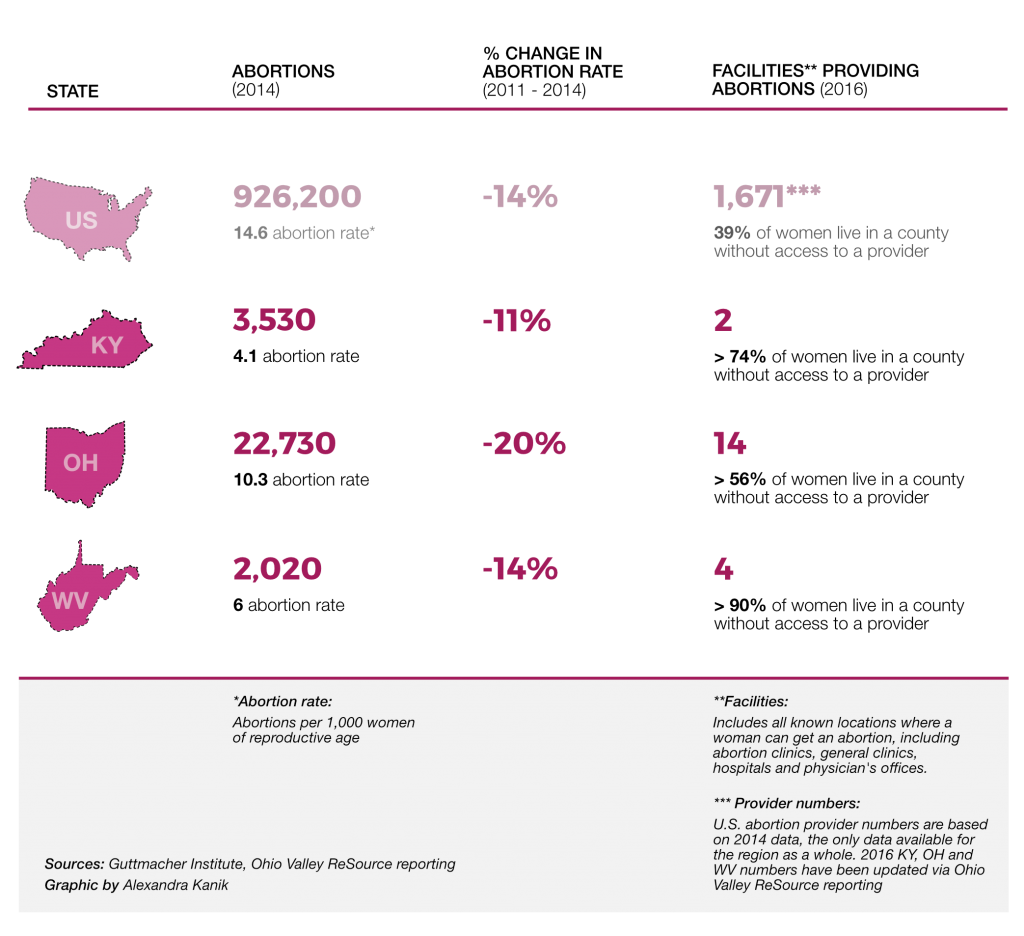

That leaves Kentucky with a single abortion clinic. A few weeks later, a clinic closed in West Virginia, leaving that state, too, with a single clinic. In Ohio, there are now 9 abortion clinics, down from 18 in 2011, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a nonprofit research center that gathers reproductive health data.

Explore the interactive maps >>

For all the talk of potential changes in the Supreme Court’s view of the landmark Roe v. Wade ruling on abortion, Wells said an effective erosion of the rights that decision established is already underway at the state and local level.

“Roe v. Wade — it doesn’t matter if they overturn it or not, if they have enough restrictions on abortions that people are unwilling or unable to meet,” she asked, “what’s a right if you can’t access it?” Then she went back to packing up her office.

State Restrictions

The Roe v. Wade decision in 1973 established abortion rights. By the 80s, Wells said, abortion was widely viewed as a medical option, one performed by many private doctors. Health departments made referrals. There were a half dozen clinics in Lexington and Louisville.

But the public protests, going back to the mid-80s when protesters routinely chained themselves to clinic doors, had an impact.

Slowly, Wells said, the number of doctors who were willing to perform abortions shrank. There were in turn fewer doctors who were being trained to perform abortions. Changes in available medicines had an effect as well. The “morning after” pill became available, and more women had access to longer-lasting contraceptives.

While the medical landscaped broadened, the political landscaped narrowed. Over the same stretch of time, legislatures across the country enacted laws restricting abortion.

In Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia, there is a 24 hour waiting period between making contact with an abortion provider and having the procedure, according to the Guttmacher Institute. A woman must also receive information discouraging her from abortion.

Wells said that in 2016 the state asked that her clinic obtain a license to perform abortions. The clinic had previously acted as an independent doctor’s office that doesn’t require such a license.

Wells said she tried to comply with the state request. But, she said, “there was always something wrong with the paperwork.”

For much of the last year, she has not been able to provide surgeries. In January, the Kentucky Attorney General denied her license application. At the same time EMW also lost the lease it had held since 1989.

Wells said fighting back didn’t make sense.

Celebrating Closures

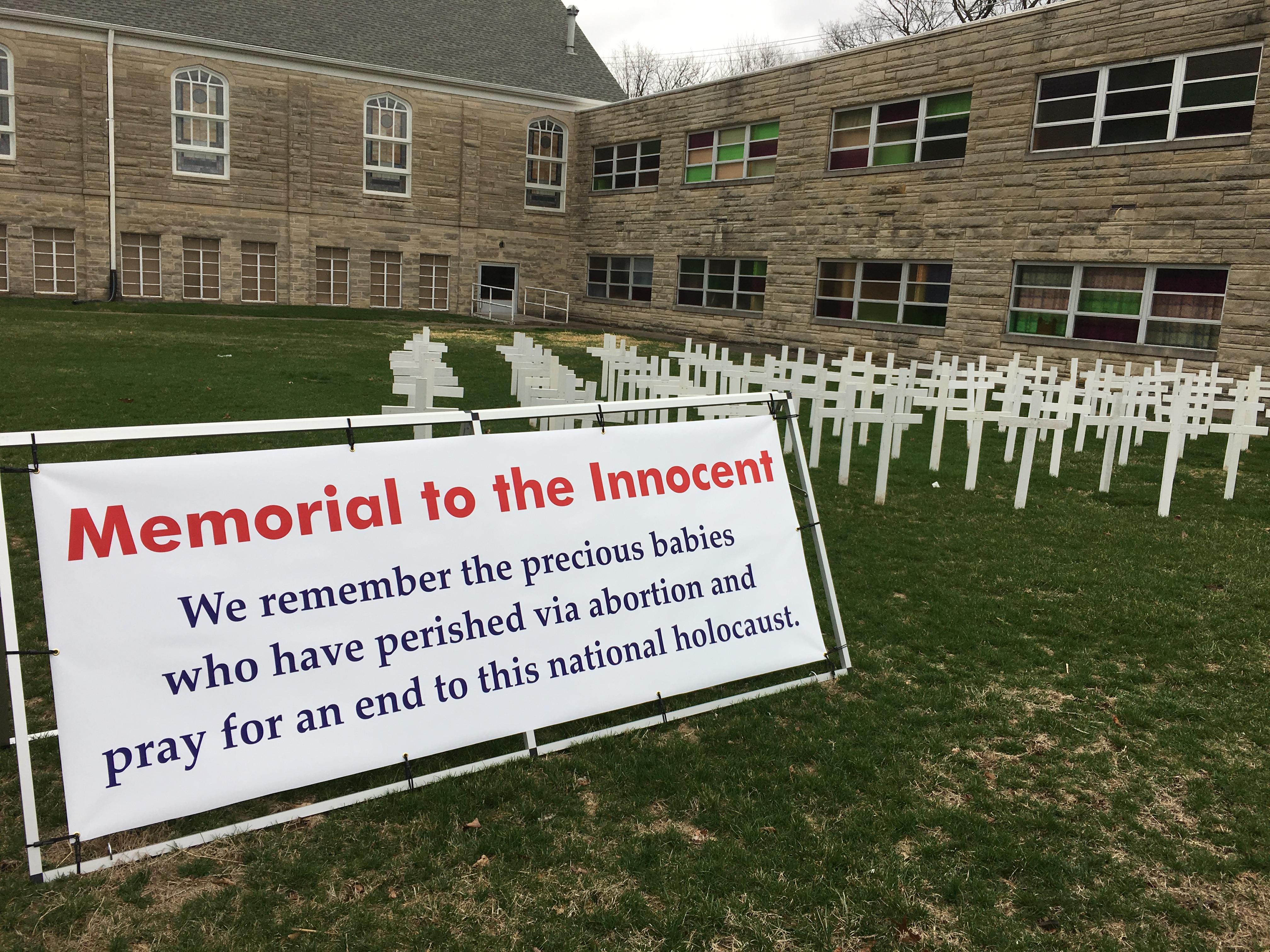

Pastor Jared Henry leads a congregation of 200 at Lafayette Church of the Nazarene, less than 2 miles from the EMW clinic.

When Wells lost her fight, Henry celebrated.

“All that they did was kill babies there,” he said. “I think that our city, our state, our world is better off even if it is one less (clinic), praise be to God.”

Soon after he became pastor, Henry discovered the protesters gathered at EMW each Thursday and Friday. Henry said he often prayed with women who were willing to pray with him and prayed for those women who were not. Members of his small congregation gave money to the cause and contacted lawmakers to express their views.

Henry said supporting life is crucial to the mission of the church, including ending abortion but also supporting adoption and foster care. That, he said, is critical.

“It’s not just saying, ‘this is wrong.’ That’s kind of like a doctor saying, ‘you’re sick.’ I want him to tell me what to do about it,” he said.

Although he said he and his congregation have contacted political leaders about abortion, he thinks the issue has gotten too politically charged.

“My biggest problem it that sometimes politicians use it to garner votes on one end of the spectrum or the other. Politicians very rarely ease anything, it usually gets it more fired up,” he said.

Limiting Access

Wells declined to talk about the protesters at her clinic. But, she said, the tone of the debate has become more vicious over the years. The language has become more graphic. And, she said, “alternative facts” more rampant.

“I just don’t have time to dispute all the misinformation the, quote, government, unquote, comes up with,” she said.

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSource

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSourceSharon Lewis is executive director of Women’s Health Center of West Virginia, that state’s sole abortion clinic. She said as a provider she will find a way to comply with new rules. But she said limiting access — making people have to find transportation to go farther, to find money to pay for child care and possibly two days in a hotel — that makes a legal medical service too expensive for many.

“What it could do is send us back to the days when women died because they had unintended pregnancies,” she said.

Long Term Impact

Earlier this year the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a report showing a leap in maternal mortality. Dr. Caitlin Gerdts is Vice President for Research at Ibis Reproductive Health, a nonprofit group that advocates for reproductive rights. She said it’s difficult to find a firm cause and effect between that maternal mortality data and the decreased access to abortion.

For example, she said, the CDC points to the effects of chronic diseases such as heart disease. But, she said, research has shown that restricting abortion does have health effects.

“There is a substantial physical health, mental and economic health of being denied a wanted abortion,” she said.

Pastor Henry said in his experience the women he counsels suffer from emotional pain. He said the closing of the Lexington clinic allows for a shift in focus of his church’s pro-life ministry.

“Maybe this will allow us to focus more on issues of adoption and foster care,” he said.

“We are not hear to beat people up,” he said. “You did wrong and it was a serious wrong, but God can forgive, so let’s move forward.”

However, members of his congregation also took a recent road trip to Louisville. There they demonstrated in front of Kentucky’s sole remaining clinic.

Kara Lofton, Appalachia Health News Coordinator for West Virginia Public Broadcasting, contributed to this report.