News

Trying Times For Transit: Rural Systems Face Flat Funding And Rising Demand

By: Becca Schimmel | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

Thelma Daulton goes to the salon to get her hair done at the same time every Friday. She gets picked up at her house and greeted by one of many familiar faces from the Rural Transit Enterprises, Coordinated, or RTEC.

Daulton is 95 years old and has been riding the public transit system in Somerset, Kentucky, for about 15 years. Daulton said her daughter would like for her to move closer to Bowling Green, but Daulton likes her community and has no intention of leaving.

“I want to stay here. I want to be in my own home if I can as long as I live,” Daulton said.

Daulton is just one of many seniors in small towns and rural areas who want to age in place and remain connected to their community. Access to transit helps make that possible. But the RTEC is not just the only transit system in Somerset, it’s the only one for the 12 surrounding counties.

Mary Denny has been driving for RTEC for 5 years. She said many people in her community would be stranded or home bound without the service, not just seniors.

“It doesn’t just pertain to just elderly. We have anywhere from young individuals that’s struggling, low income, that’s struggling to make ends meet that we’re able to help and assist,” Denny said.

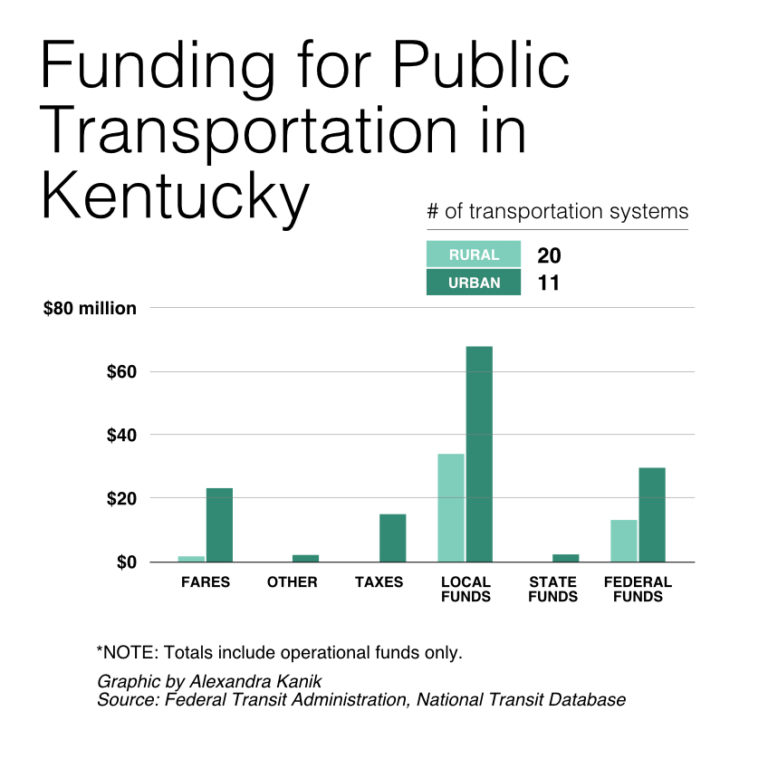

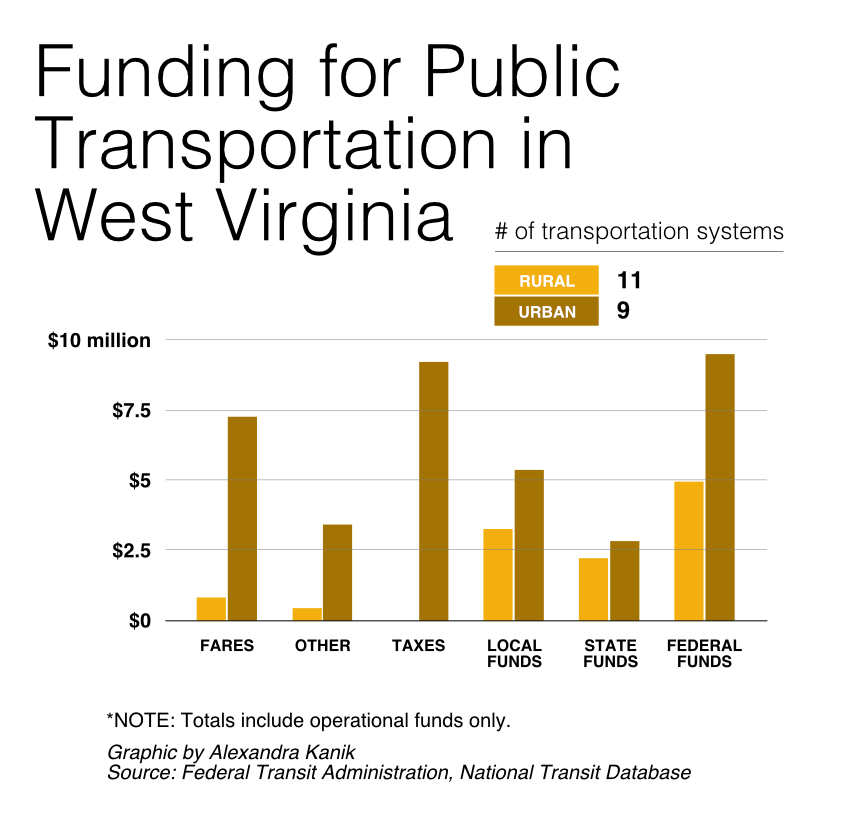

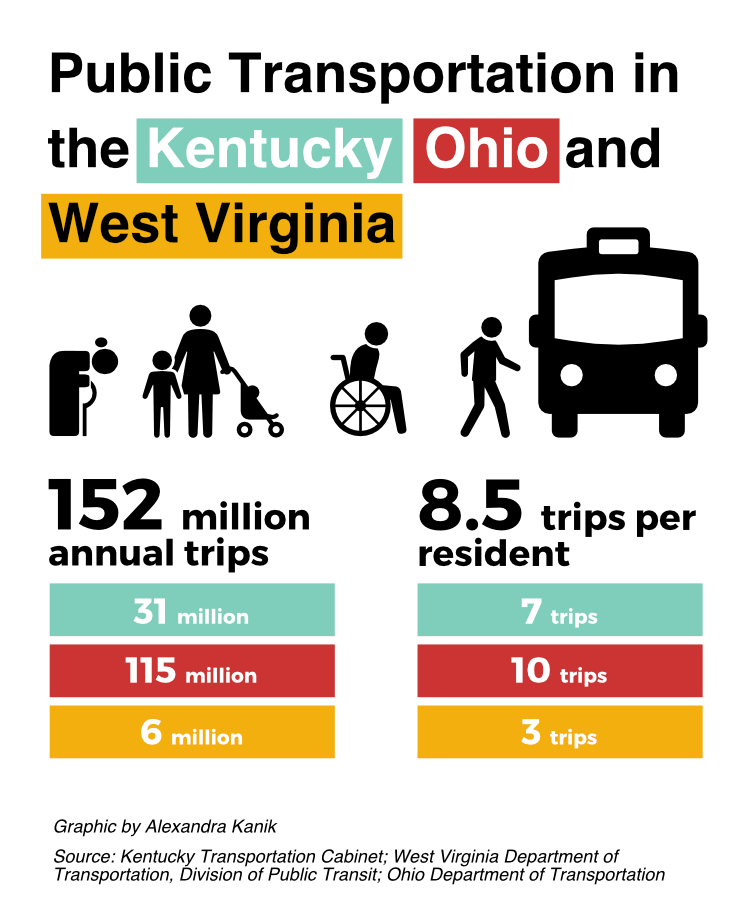

Compared to national averages, the Ohio Valley has a higher percentage of senior citizens, people with disabilities, and people living on low incomes — all groups likely to depend on transit. And a great number of them live in rural areas and small towns. Public transportation can make it possible to keep a job, reach a doctor, or just get your hair done. But transit experts in the region worry that funding is not keeping pace with demand.

Falling Behind

Juva Barber is the Executive Director of Kentuckians for Better Transportation, a statewide association advocating for all modes of transportation. Barber said in 2020 Kentucky will need $10 million from the general fund just to keep services as they are now, not including any improvements.

“We have to do something because if we don’t do something we fall farther and farther behind.” Barber said, adding that the effects can be felt far beyond just those who ride the bus.

“When you’re looking for a workforce, if that workforce can’t get there that puts you further down on the list when it comes to site selection so that impacts economic development,” she said.

Barber said there needs to be increased investment in infrastructure. No pothole will repair itself and no bus will avoid a trip to the maintenance garage.

Charles Rutkowski is with Community Transportation Association of America, a national organization that works with rural transit systems. He said every patient, customer and student represents income, revenue, and economic development for that health care institution or college. He adds for every $1 invested in transit there’s a benefit of $3.50 to that community.

“It provides jobs on a very basic level. It provides jobs for bus drivers, bus mechanics, dispatchers, schedulers, managers etc.,” Rutkowski said. “But it also transports a lot of local folks to jobs. And some of those individuals probably could not access those jobs were it not for the existence of public transit.”

Rutkowski said providing access to public transportation helps some lower income individuals break out of the cycle of poverty. He said it also enables seniors such as Thelma Daulton to live in their own homes and retain their independence, which often costs less than an assisted living facility.

Rural Challenges

A new report from the American Public Transportation Association lays out some of the numbers behind transit’s impact on rural communities.

The APTA found that while rural population is declining, ridership in rural areas has increased over the past 8 years. In fact, rural ridership grew far faster than did public transit demand in cities (when measured on a per capita basis).

The rural demand is largely due to older residents, people living on low incomes, and people with disabilities. Older folks make up a larger portion of rural communities than in urban areas, and rural poverty rates are higher than urban poverty rates across the country. That difference is especially high in the south.

The report includes a map showing the convergence of all three of these factors in the Ohio Valley region. Kentucky, West Virginia, and southeastern Ohio have high percentages of seniors who are both underprivileged and living with a disability. In many counties in the region 15 percent or more of the population fits this description. The U.S. average is about 10 percent.

And yet, the APTA found that per-capita spending on rural public transit spending is lower than in urban areas.

“Homebound Without Us”

Kirt Conrad is the CEO of Stark Area Regional Transit Authority in Canton, Ohio. He said the state has supported the public transit system but the needs are outgrowing what has historically been provided.

“Every two years we have to go back to the general assembly and set those funding marks. We have no guaranteed funding sources for transit at the state level,” Conrad said.

Conrad said lower income people who rely on public transit often have no slack resources, and if they’re relying on transit services to get them to work the service has to be reliable. Conrad said they also transport about 170,000 people a year who qualify for public assistance under the Americans with Disabilities Act.

“We go to their house and take them to either work, school, or the doctor’s appointment. Without us those 170,000 people would be homebound,” Conrad said.

“Opens your eyes”

Bowling Green, Kentucky, resident Scott Henry never expected to need a service like that.

“Being a healthy person all my life I never ever thought I’d be in a situation where I’d have to count on para-transit transportation to get back and forth to work every day,” Henry said.

But about a year ago Henry’s knee collapsed, became infected and he wasn’t able to get a knee replacement. He’s been unable to drive since.

“It opens your eyes if you don’t have something like that. You can’t do your job, you can’t go to the doctor, you can’t get groceries,” Henry said. “You can’t do anything and living alone I had no one to help me.”

“It opens your eyes if you don’t have something like that. You can’t do your job, you can’t go to the doctor, you can’t get groceries,” Henry said. “You can’t do anything and living alone I had no one to help me.”

Henry said arranging private transportation can cost about $200 a day. He’s had to cancel doctor’s appointments and even surgeries because he couldn’t get a vehicle to the hospital. Then he learned he was in the right area to use the city’s transit, BG Go. That gave him some motivation.

“So when I got that spark then it was like, I was going to do this today, I was going to do that today. I was going to get up today. I was going to do this by myself today,” he said. “I was going to get dressed like I was going to work today, and so that really did it. Without this I couldn’t be here today.”