News

Speedy Decision: Are Poultry Processors Pushing Safety Limits?

By: Nicole Erwin | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

After serving five years in the Navy Tyler Dunn has returned home to Hickman, Kentucky. These days, if he isn’t at work at the local liquor store or completing assignments for a business degree, you might find him surrounded by one of several stray cats he saved from a parking lot.

It’s hard to reconcile this image of Dunn — military veteran, serious student, and sensitive pet owner — with another fact about his life. Nearly ten years ago he was fired by Tyson Foods, in Union, Tennessee, for animal cruelty.

“I worked there for two years before I was let go there for, ‘animal cruelty,’ I wouldn’t call it animal cruelty,” said Dunn.

He was fired after he appeared in an undercover video recorded by an animal rights group that showed what happens in the part of the plant called the live hang.

“Two people would get beside each other in the front of the line and then they would start hanging, like fast,” Dunn remembered. He explained the game he and another employee had played to see who could hang the most birds. “So instead of 24 [birds] a minute, which was minimum, we might hit 50 or more a minute and they called it unnecessary force.”

Other employees in the video admitted to breaking the backs of birds as they would peck, claw and defecate on workers.

It’s not the only time animal rights groups infiltrated the company’s operations. In an email, Tyson wrote that in an effort to increase animal welfare efforts it has launched “the industry’s largest third-party remote video auditing program,” covering 33 poultry plants, and took other measures to improve handling of birds.

But industry critics say the underlying problem is the speed at which employees must do their work in plants where 140 birds may go by in a minute.

“I feel like the workers aren’t bad people,” Debbie Berkowitz said. She’s a senior fellow with the worker rights group National Employment Law Project and a former senior official with the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. She said the higher line speeds increase emotional and physical stress for the workers and animals.

“There is a direct connection. If you make workers work at breakneck speed they don’t really have a choice,” Berkowitz said. “The live hang is probably the worst and most disgusting job in America.”

Berkowitz is among a group of worker and food safety advocates concerned about a proposal from the poultry industry which would allow an even faster rate of work in parts of some processing facilities. They warn that higher line speeds increase the risk for foodborne illness and injured workers in an industry with an already spotty safety record.

Greater Efficiency

The National Chicken Council represents the industry. Spokesperson Tom Super said the motivation behind the higher line speeds is to keep up with international competitors.

“To modernize the system, and really so we can operate more effectively and efficiently,” he said.

In September, the council petitioned the USDA to allow plants that have operated under what’s known as the New Poultry Inspection System a waiver that would remove the speed limit on some bird processing.

Plants operating under that system can now operate as fast as 175 birds per minute. Super said a government pilot program has been operating for almost 20 years and now plants should be able to do more.

“It has proven safe for the safety of our workers and it has benefited American consumers as well,” Super said. “We have science on our side and we have almost 20 years of data. I don’t know any other pilot program that has lasted for 20 years.”

“All I Could Take”

The industry waiver targets the part of the plant where organs are removed from the carcasses, called the evisceration line. Super said changing line speeds here would not affect other operations of the plant. Berkowitz and others familiar with the process disagree.

“If they are going to allow 140 birds per minute to whiz by– now they are going to go to 170 or 200 or 250 — that means that many more birds are being killed, per hour,” Berkowitz said. “Which means live hang has to hang that many more birds.”

Berkowitz said this is also where most worker injuries occur. Federal statistics show animal slaughtering and processing facilities are the 6th most dangerous workplaces for severe injuries. According to a Government Accountability Office report, most musculoskeletal injuries caused by repetitive movement, such as carpal tunnel syndrome, are not reported by workers.

Berkowitz said she has interviewed many poultry workers who face that situation. “They’re scared that they’re going to get fired if they report an injury or if they file a worker’s complaint,” she said. “So they just go on unpaid leave and they take care of it themselves.”

Paducah, Kentucky, resident J.T. Crawford said he couldn’t imagine trying to work at any part of the plant with higher line speeds.

“I was at the chicken plant for one night. That was about all I could take,” he said.

Crawford said other employees encouraged him, saying he would pick it up eventually. He decided it wasn’t worth the risk of injury.

“Night after night after night, pushing your body to the absolute maximum to get these chickens on these lines so that they could be cut,” Crawford said. Today, Crawford works as an assistant editor for Paducah Life Magazine.

Tyler Dunn said his two years in the industry were challenging, especially the work in the live hang area.

“In the beginning I was sick, I was weak. It felt like I had the flu,” he said. “My body was aching, and from what I understand, from talking to a few people, there was a few folks that had the same symptoms that I did.”

He suspected it was due to the foul air strong with the smell of chicken feces and occasionally from rotting dead animals.

“But you get used to it. I got where I couldn’t smell myself, but if I got off work other people around me could,” he said.

Dunn also reported injuries to his hands. “We wore gloves, rubber gloves and then cotton gloves underneath that, but it still wasn’t a lot of padding against those shackles,” he said.

Dunn said he missed work for a month because of an infection in a finger that sent him to a doctor. “They had to cut it open and I was in a hand brace for about a month.”

30 Seconds

Retired USDA food safety inspector Phyllis McKelvey was stationed at the first plant to pilot the new poultry inspection system in 1999. Today she works with the Government Accountability Project, an advocacy group, speaking out against higher line speeds and the risks for workers and consumers.

She said under the new system only one federal inspector is responsible for viewing birds that come through the evisceration line.

“You had less than 30 seconds to inspect the chicken. How can you look at the front, back, up and down and inside a chicken in 30 seconds?” McKelvey asked before answering her own question. “There’s no way.”

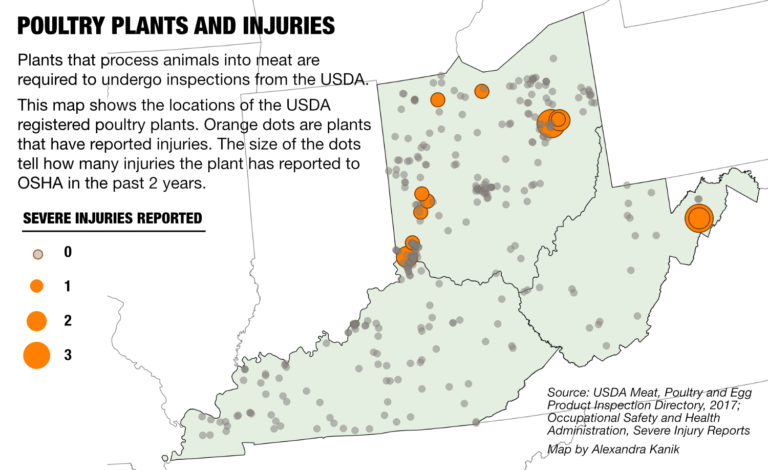

The program is optional and so far only 20 poultry processing plants operate under it. Pilgrim’s Pride in Moorefield, West Virginia, is the only poultry plant in the Ohio Valley region operating under the new inspection system. Federal data on workplace injuries show that facility had five severe injury reports in a two-year period, more than any other facility in the three-state region.

In its petition for higher line speeds, the chicken council argues that more plants will choose to operate under the new inspection system if they have the benefit of higher speed and efficiency.

McKelvey said the higher the line speed the less accurate the operation of the machines.

“These machines will pull the viscera, which is the guts of the chicken. And a lot of times the guts hang on their prongs and those machines just get covered up in guts, which is slinging manure all over the product,” she said.

In the live hang section, McKelvey said equipment failures would also occur in the stun bath, where birds are shocked with electricity. That would send fully conscious birds to a machine that would sever their necks.

“If the line is going too fast you have a lot of birds that don’t get stunned,” she said. “So you’ve got some birds going into the scald vats, alive.”

The USDA describes the new inspection system as more science-based in that it requires that all poultry facilities perform their own microbiological testing along with two federal inspectors. This leaves one inspector to view the carcasses.

But with fewer inspectors, McKelvey argued, plants are relying on more chemicals like peracetic acid or food bleach to reduce chance of food contamination.

“And if they don’t have a proper air system these chemicals are causing people to sneeze and cough and even at that rate it gets so bad we’d have to shut the line down,” McKelvey said.

Process Control

The National Chicken Council petition said that the requested waivers will depend on a plant’s ability to maintain process control.

“We wouldn’t operate at any speed limit that we could not maintain process control,” spokesman Tom Super said. “If a company can’t keep its food safety record straight, if it can’t adequately protect its employees, if it can’t keep up with sanitation, that would be a loss of process control.” At that point, he said, USDA would step in.

Tyson Foods has two plants operating under the new poultry inspection system but has not voiced support for the chicken council petition. Tyson spokesperson Worth Sparkman said in an email that “policy and practice encourages plant team members to stop the line at any time for worker or food safety issues.”

Sparkman also said that Tyson is committed to achieving a 15 percent reduction in incidents reported to OSHA and to running processes “at a speed according to the number of people available to work.”

OSHA records show Tyson Foods and Pilgrim’s Pride had the highest number of severe injuries reported among animal processors over the past two years, and the companies rank among the top three employers with the highest rates of severe injuries reported.

Pilgrim’s Pride did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

McKelvey said that providing a safe workplace is difficult with the small workforce that the federal government employs to ensure that plants fall in line with the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970, which requires plants “assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women.”

During a 2015 Congressional hearing, OSHA’s former director David Michaels said his was a small agency.

“With our state partners we have approximately 2,200 inspectors responsible for the health and safety of 130 million workers, employed at more than 8 million work sites around the nation.” That works out to about one compliance officer for every 59,000 workers.

Michaels left OSHA at the end of the Obama administration. President Trump has not yet named a replacement.

Letter of the Law

Thirteen groups representing worker rights, consumer safety, public health, and animal welfare met recently with the USDA to urge the agency to reject the poultry industry effort to increase line speeds.

The Southern Poverty Law Center is one of the groups that attended the USDA listening session.

In a letter to the USDA, the SPLC said “in addition to creating bad policy, approving the NCC’s petition would violate the law.”

The SPLC claims that the USDA is not following the requirements of the Administrative Procedure Act, a law that is supposed to keep federal agencies transparent and accountable to the public, because the agency has not published relevant documents on the Federal Register.

This has created unease among food safety advocates because they are uncertain how the USDA plans to approach the rule making process. A letter from the USDA in response to the National Chicken Council’s petition refers to the requested waiver as a policy change.

Berkowitz said she is afraid this could result in decision making behind closed doors.

The petition is online for public comment until December 13th. A USDA spokesperson said the department’s practice is to withhold comment on a petition under consideration.