Queer Performance Art: Using the Body to Talk About Identity

By: Anna Turner, Seth Eggenschwiller

Posted on:

Anna Turner and Seth Eggenschwiller visited the fifth floor of Seigfred Hall to view the School of Art and Design’s new gallery titled “Temporal and Corporeal: A Broad Scope of Performance Art.” The artists and performers had some strange things to put on display, but each piece has a story and a purpose.

Audio PlayerIt’s 6:30 on a Thursday night, and there is a crowd of people gathered in a large, mostly empty white room. Everyone’s attention is fixed on what’s happening in the center, something confusing….and a little bizarre.

In front of the crowd a woman sits on a hay bale, wearing nothing but ragged maroon overalls. She’s holding what looks like a jaw with fossilized teeth, and she’s violently scrubbing it with a toothbrush.

Directly behind HER stands a naked woman silently screaming. Visitors continue to fill the room, wandering around to check out the other projects that are on display. But perhaps the most striking spectacle in this white room is tucked away in a corner

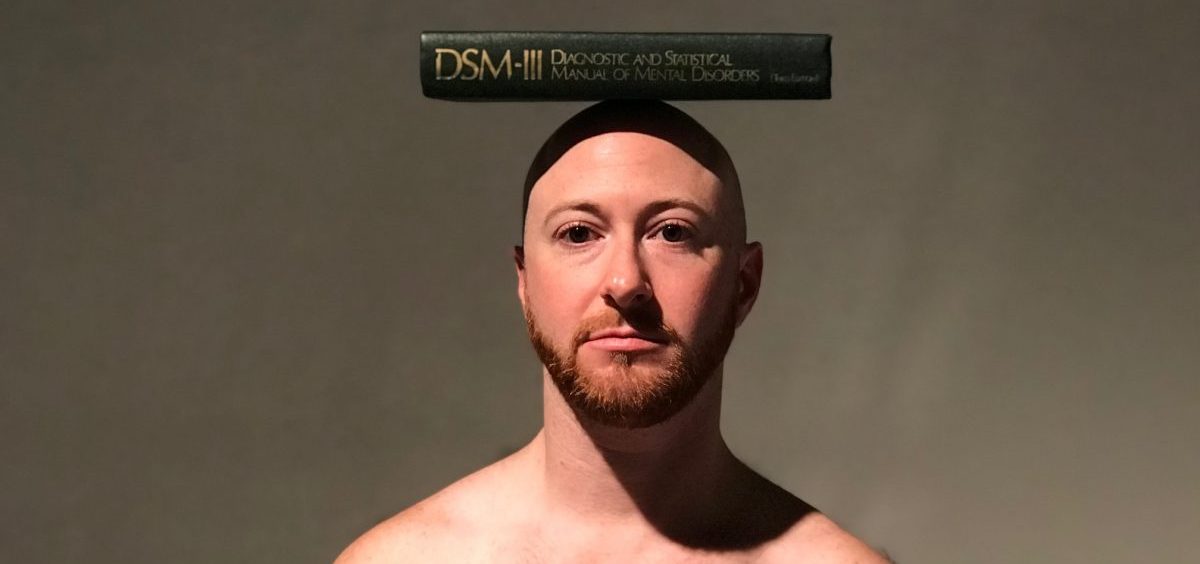

There…silent, motionless and fully nude, is Kris Grey. Kris is a genderqueer performance artist who uses their own body as a medium to create their work. On top of Kris’ head sits a copy of the DSM, or The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Kris identifies as transgender, meaning they don’t identify with the gender they were assigned at birth. They also identify as genderqueer, which can mean something different for everyone. For Kris, their art is all about throwing out what we understand to be masculine and feminine.

“I am often projecting my own fantasies and ideas about what an object might look like if it was outside of the standards of binary gender, thinking about, you know, what makes things masculine, what makes things feminine, how we can refute those categories in the first place,” Kris tells us. “And I am also doing that very same project with my body.”

For the final performance of the evening, the people still left in the gallery are moved downstairs to a different room. As everyone files in, we are each handed what looks like a larger version of a paddle ball. Each person is given the same instructions for their ball: Just keep bouncing.

Danielle Abrams is an African American, Jewish, and queer artist. She says all those different categories aren’t separate parts of herself but just who she is.

“How is your queer identity shaped by the fact that you’re working class or you know how is your African American identity shaped by being queer. And that really presented the thesis of everything that I do right now as an artist.”

Artists like Kris and Danielle say their art is important because they believe in seeing people as they want to be seen.

“They may not otherwise care about bodies like mine or my body in particular,” Kris says, “but if I appear before them in a state of extreme vulnerability, people begin to care.”

Both Kris and Danielle started with more traditional forms of art but they both learned the body itself is a powerful tool for expression.

Kris started out working in clay, and views the body in a similar way.

“The body is a material that one can mold and one can shape and one can change and the body is constantly changing, you now, in that we are always becoming ourselves. So I use my body just like I use any other sculptural material.”

Danielle describes her transition in one sentence: “I had much more complex things to say than I ever could say with paint, so that was when I began to start to use my body and objects.”

Artists like Danielle and Kris, who are involved in a style of art that’s about breaking down boundaries, are significant. They make and perform things that can be weird or a little “out there,” but it makes people pay attention. It can be difficult for people in the LGBTQ community or people who aren’t white to have their voices heard. This is what makes performance art that’s created by people in these communities so important. Artists like Kris and Danielle are devoted to making work that makes space for both education and diverse communities.