News

Rain Causing More Than Rotten Tomatoes for Ohio Valley Farmers

By: Kaitlin KulichBy: Kaitlin Kulich

Posted on:

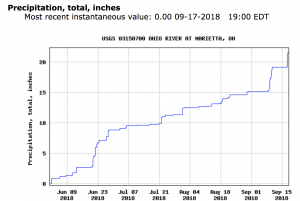

The precipitation average so far this year for Southeast Ohio is 34.75 inches, which is nearly 10 inches above normal, according to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources. Farmers in Athens County and along the Ohio River basin are hoping for less rain next year in order to reclaim what Mother Nature took from their fields and wallets.

“Rain really sucks,” said Craig Ponchak, a tomato farmer from Waterford.

A large portion of Ponchak’s 5,000 tomato crops rotted away because of large amounts of rain. He sells his tomatoes at the Chesterhill Produce Auction in Chesterhill, and in a few local stores in order to provide for his family.

“I’ve been farming since I was 11,” Ponchak said. “We used to grow twice, three times as much as we do now.”

Ponchak said he’s already thinking about planting fewer tomatoes and more broccoli and cauliflower next year because, according to him, those vegetables tend to grow better with more rain.

He could be on the right track, considering the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) predicts spring rainfall and average precipitation are likely to increase and intensify in Ohio.

The Science of Summer Rain

The soil along the Ohio River is ideal for growing tomatoes according to Dr. Matt Kleinhenz, a professor of horticulture and crop science at The Ohio State University who studies vegetable crop quality. However, Kleinhenz said farmers, especially tomato farmers, along the river will have fewer field work days as springs in Ohio become rainier.

“Tomatoes grow well in 65 to 85-degree weather and it’s best to have water come from irrigation systems, not rainfall,” Kleinhenz said. “Irrigation is more gradual and foliage stays dry.”

Kleinhenz said it is important to keep foliage dry in order to prevent it from burning in the sun or rotting away too quick.

Even though farmers along the Ohio River may have irrigation systems, their fields, and ultimately their crops, can’t help but become saturated if the river floods.

Finding a New Way To Stay Afloat

Mitch Meadows owns Mitch’s Produce and Greenhouses in Middleport, Ohio, and his tomatoes were impacted by flooding from the Ohio River. Meadows said he planted his tomatoes later this year compared to other years because flood waters from the Ohio River engulfed his fields.

“I didn’t get to start until mid-April,” Meadows said. “Seventy-five percent of my ground was under water for 30 days. It doesn’t matter if your soil is good for growing tomatoes because if it’s flooded you can’t do anything about it.”

Meadows said because he started late, he wasn’t able to grow as many tomatoes. In fact, he grew about half of the tomatoes he is used to growing, in turn reducing his main source of income.

“If I had any advice for young farmers it would be to diversify your crops or find another job that can get you some benefits,” Meadows said.

Two years ago Meadows had to become a bus driver because it not only paid well but provided him with health insurance he never had as a farmer. He still farms but he said he needs to plan better for the future.

“If it’s gonna be rainy like this again I’m probably going to grow different crops,” Meadows said. “ I don’t want to see my tomatoes bobbing up and down in the flood water.”

Kip and Becky Rondy of Green Edge Gardens had a successful tomato crop this year despite the rain because they set up high tunnels. High tunnels are a support system for crops. The bases are usually made of rot-resistant wood and are anchored to the ground. Protective coverings are attached to the bases and arch above the vegetables. They can mitigate the problem of wet springs and climate can be moderated within them.

“Our tomatoes are just fine,” Becky said while filling a bag of tomatoes for a customer at the Athens Farmers Market. “People don’t use high tunnels and I don’t know why. You have to use high tunnels or spray or do something if it’s gonna be wet like it’s been.”

The Rondy’s are a rare case when it comes to small, family-run farms, it seems.

Edd Perkins of Sassafras Farms in Athens County is unable to afford high tunnels that would help prevent his tomatoes from rotting. Perkins said there is a lot that goes into having high tunnels that he doesn’t have.

“You have to have some kind of natural water source, like a river or a pond that feeds into your high tunnels, and I don’t have anything like that.”

Perkins went on to say creating and maintaining high tunnels, which will last more than one season, demands more time and money than he has.

ThomasFord, as horticulture educator at Penn state said a high tunnel can cost between $11 thousand to $15 thousand and that his studies show it is possible for growers to make this money back.

Despite Ford’s study, Meadows and Perkins are still unable, or unwilling, to invest in high tunnels. Regardless of the possible economic hardships that come with running a small-scale farm, farmers like Meadows and Perkins continue to grow and sell produce because they believe the positive aspects of farming outweigh the negatives.

“I’ve been growing for 25 years,” Meadows said. “It’s a good way of life. I never had a boss and I enjoy what I do. It’s hard work but I don’t mind it.”