Food Waste That Doesn’t Go to Waste

By: Claudia Cisneros

Posted on:

ATHENS, Ohio – The carrots you did not eat or the broccoli you left on your plate will get a second chance at the Ohio University Compost facility. A two-man staff in a large truck picks up the leftovers every morning even before the sun rises. Their first stop is at the Culinary Services Headquarters, where all the food for the campus diners is prepared. With 3.8 million meals served every year, Culinary Services is one of the largest self-operated non-franchised dining services colleges in the U.S. And the compost facility processes 100 percent of this pre-consumer food waste.

At the Culinary Services headquarters, the men pick up 10 large green plastic bins containing the leftovers of the meals prepared. “We have apples, carrots, lettuce”, says one of the men. Before heading to the dining halls, they leave 10 clean containers ready to be filled the following morning. Within two hours they have repeated the operation in all the campus dining halls and the truck heads to the Ridges, where the composting plant is. The sun is up and soon a synchronized chaos begins.

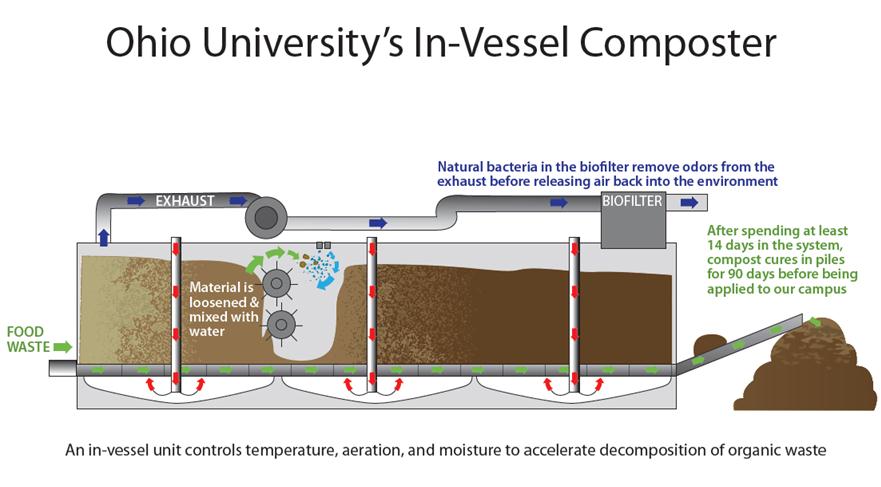

Each of the 40 green bins collected this day goes up an elevator. At 10 feet high, the bin is emptied over a 1-ton mixer. Here, wood chips will be added to the food waste as bulking agents. Then the mix goes up through a belt to end up in a 4-ton vessel where it will be kept 14 days. Here, the mix temperature (120 to 150 degrees Fahrenheit) and moisture will be controlled.

“We are processing around 9,000 pounds today, which is on the average,” explains Dave “Moose” Moorehead, one of the three staff members at the composting facility. Fourteen days later the mix will be pushed out of the vessel and put into piles on the ground in a series of 200 foot-long “windrows” where the compost will age and be filtered for any non-degradable material.

“We are keeping it out of the dump, which is a good thing, and reusing it as fertilizer,” Moorehead said.

When ready, the compost will be used as nutrient-rich fertilizer for the campus intramural fields, flower beds, and landscaping. This saves the university around $130 to $150 per ton of waste composted – the cost of sending the waste to a landfill.

Even when working at full capacity, the two metal in-vessel compost machines do not emit heavy odors because natural bio-filters are in place to reduce strong smells. The entire facility is sustainable. Most of the facility’s energy comes from solar panels on the roof and ground.

The water to clean the bins is collected from the rain through a drainage system on the roof and kept in a container underground. This composting facility is in itself the closest you get to an ecological utopia. So, next time you stop and smell the flowers on campus, you can rest assured that the broccoli you left on your plate, or that carrot you did not eat, is back in nature.