News

From Russia, With Loot: KY Aluminum Company’s New Russian Partner Raises Concerns

By: Sydney Boles | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

A large whiteboard in an Ashland, Kentucky, unemployment office is covered with a list of companies that are currently hiring. Senior career counselor Melissa Sloas said that just a few years ago, that board was a lot emptier.

This corner of eastern Kentucky has long struggled to make up for losses in mining and manufacturing. Unemployment in the Ashland area is still around 6.3 percent, well above the state average. Career center employees said workers are anxious about the closure of longtime employer AK Steel, which announced in January it would close its Ashland plant this year.

Anticipation has been brewing here about a potential new major employer, aluminum processing company Braidy Industries.

The first new aluminum rolling plant in the U.S. in 37 years, Braidy Industries’ Atlas plant promises to be greener and more cost-effective than other rolling mills. Business leaders hope the plant will attract auxiliary businesses to the region.

“For years we’ve seen industry leaving, the workforce leaving the area because there were no jobs,” said Justin Suttles, another career center employee. “And so this is the injection we need to attract more businesses to the area.”

Braidy Industries was such an attractive project that Kentucky’s Republican Gov. Matt Bevin offered significant tax breaks and invested $15 million in taxpayer dollars through Kentucky’s private investment company, Commonwealth Seed Capital. Effectively, Kentucky taxpayers are part-owners of Braidy alongside CEO Craig Bouchard.

But even with that public cash infusion, Bouchard and Braidy needed more capital investment. They found it from an unusual source.

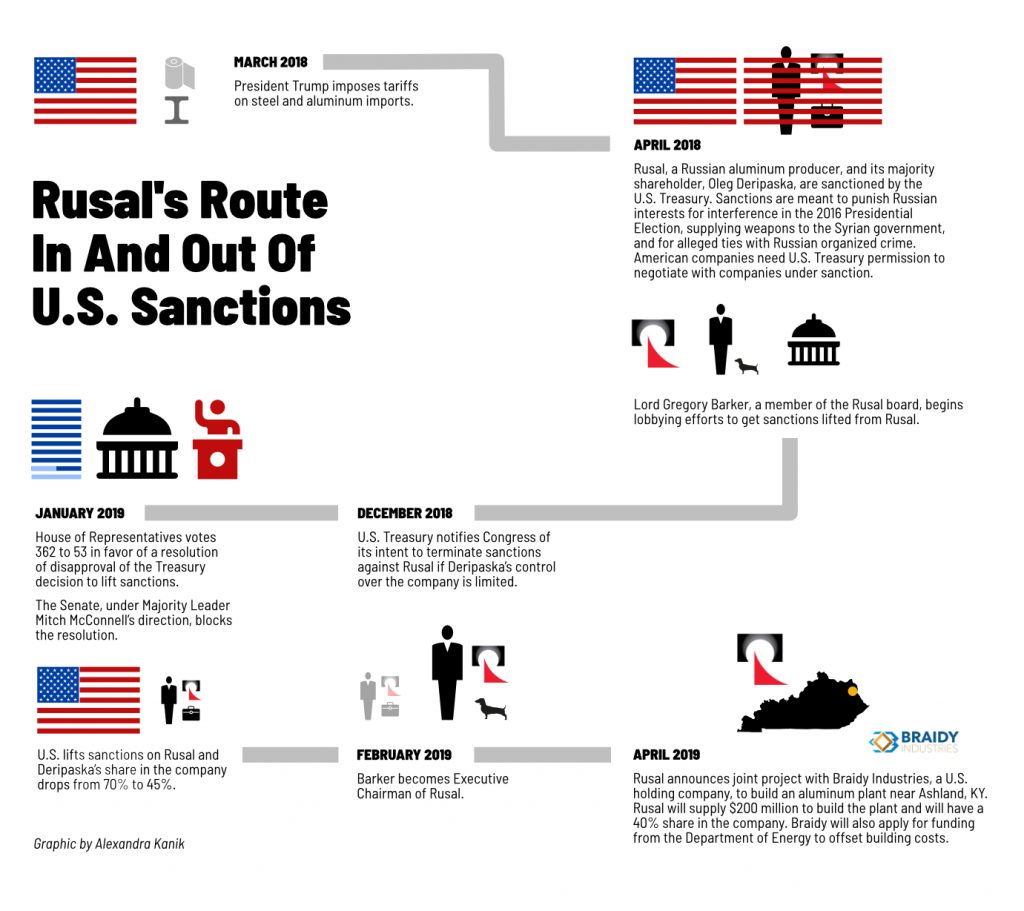

At an event with Gov. Bevin at the New York Stock Exchange in April, Bouchard announced a $200 million investment from Russian aluminum giant Rusal, the world’s second-largest producer of that commodity. In exchange for its investment, according to a Rusal press release, the company would have a 40-percent share in the company.

“We are going to lead the world in highest quality, lowest cost, and the least use of carbon from start to finish in the manufacturing process,” Bouchard said at the NYSE.

Up until four months ago, Rusal and its owner, Oleg Deripaska, were under federal sanctions for what U.S government officials called “worldwide malign activity.”

The rapid change in Rusal’s legal status, going from a U.S.-sanctioned company to a Kentucky investor in just over three months, is raising eyebrows among some national security experts. And the unusual public investment means that all Kentuckians now have a stake in a company tied to a Russian entity with a checkered past.

Who Is Deripaska?

In a telephone interview with the ReSource Bouchard said he isn’t worried about the sanctions.

“Dereg Olipaska [sic] is someone I’ve never met, never talked with, don’t know at all,” he said, mispronouncing the oligarch’s name. “Ten thousand families are relying on me and my company to secure a future that’s much better for them than the last 30 years that they’ve had.”

Oleg Deripaska was the victor in a bloody 1990s battle over the former Soviet aluminum industry and is known to be close with Vladimir Putin. U.S. foreign policy establishment considers him to be an extension of the Kremlin. In its decision last year to impose sanctions, U.S. Treasury officials outlined evidence that Deripaska has been accused of money laundering, fraud, and even ordering a business rival killed.

Treasury sanctioned Rusal and Deripaska in April 2018, over the oligarch’s Kremlin connections and Russia’s role in interfering with the 2016 presidential election, Russia experts said.

“The U.S. government theory of the case is to show this oligarch class, which may be used as extensions of the Kremlin, that they’re not insulated from that conduct,” said Michael Dobson, a private attorney who, in 2018, was on the team at Treasury that imposed the sanctions.

According to Dobson, the Treasury Department thought deeply about the implications the sanctions would have on the global aluminum market, but decided it was more important to show that no company was too big to face sanctions when they were warranted.

But as soon as the sanctions went into effect, a big-money effort began to get them lifted.

The Barker Plan

The sanctions caused the price of aluminum to soar, worrying market watchers. Almost immediately, Rusal launched a comprehensive maneuver to get the sanctions removed. The effort was so extensive that it got its own name: The Barker Plan.

Named for British MP and new Rusal chairman Lord Gregory Barker, the Barker Plan entailed months of lobbying and countless trips between London, Moscow, and Washington D.C. for the British lord.

Dobson said the scope and politicization of the lobbying campaign were unprecedented. “How many other delisting processes can you talk about in terms of somebody’s name?” Dobson said. “If you can name one other delisting process, I’ll be shocked.”

Barker successfully negotiated for Deripaska to reduce his ownership stake in the company from 70 percent to less than 50 percent. On December 19, 2018, Treasury notified Congress of its intent to remove the sanctions.

Deripaska has alleged his net worth has been cut in half as a result of sanctions, Dobson said. “He’s struggling to find business partners now, and he had to divest from significant portions of [his company].”

Dobson said the Treasury conducted a “hard scrub” to make sure Lord Barker and other leaders within Rusal were not simply stand-ins for Deripaska, but others remain skeptical.

“I haven’t heard any indications that [Deripaska] is genuinely out of the loop,” said Jeffrey Mankoff, a scholar of national security at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “The commentary at the time was, this was kind of dubious, this was a bit of legal fiction, that effectively he would still be in charge.”

The Treasury Department could re-apply sanctions if it determines that Deripaska is more involved in practice than he is on paper, Dobson said. In that case, Braidy Industries would need permission from the Treasury to continue dealing with Rusal.

Barker is set to act as co-chair of the Ashland-area plant alongside Bouchard.

Kentucky Connections

The Barker Plan rested in part on the work of a Trump-connected lobbying firm called Mercury Public Affairs. Mercury Senior Vice President Michael Crittenden declined to confirm which lawmakers the lobbying firm had contacted on behalf of the Barker Plan, but publicly available Foreign Agents Registration Act filings show Mercury lobbyists were in contact with Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s team, as well as other lawmakers, on separate projects.

When the Treasury Department alerted Congress to its decision to lift sanctions against Rusal in December 2018, Democrats in the House of Representatives worried the move would be seen as a favor to Vladimir Putin, particularly in light of concerns about the Trump campaign’s connections with Russia.

Deripaska had a long business relationship with Paul Manafort, who would later become Trump’s campaign chair. The recently released report of special counsel Robert Mueller shows that Manafort intended to use his position on the Trump campaign to pay Deripaska back for some outstanding debt. Manafort is now serving a 7-year sentence after pleading guilty to conspiracy and fraud charges.

The House voted 362 to 53 to overrule Treasury’s decision and keep sanctions. But in the Senate, McConnell marshaled opposition to the resolution, and sanctions on Rusal were lifted.

Mankoff at CSIS said McConnell’s behavior raises concerns.

“Given the inroads that various Russian operatives, including people like Manafort made into the campaign, I think it’s worth at least asking the question what the game people like McConnell are playing, is,” he said.

A spokesperson for McConnell declined to answer specific questions about the sanctions, but pointed instead to McConnell’s floor speech at the time of the delisting.

“Career civil servants at the Treasury Department simply applied and implemented the law Congress itself wrote,” McConnell said. “Treasury’s agreement maintains sanctions on corrupt Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska. It would continue limiting his influence over companies subject to the agreement.”

While Rusal was lobbying Congress for sanctions relief, Braidy CEO Bouchard was also building a personal relationship with McConnell. Industry paper Automotive News reported in March that Bouchard spent months in early 2019 courting Kentucky’s powerful senior senator in an attempt to avoid tariffs, which would raise the cost of foreign aluminum. Bouchard told Automotive News that Braidy would be importing raw aluminum from a foreign company.

Market Forces

“Rusal’s decision to invest in a Kentucky facility is certainly somewhat unusual, considering the company was under sanctions until just a few months ago,” said Christopher Clemence, editor in chief of the industry trade site Aluminum Insider. In his written response to ReSource questions Clemence added, “Given the deficit of US-produced auto body sheet, the plant is likely to emerge as a central production hub for the domestic car industry.”

Braidy and Rusal’s deal allows both entities to split tariffs imposed by the Trump administration on imported aluminum, lessening the burden on Braidy.

“You could look at the move as a clever way on Rusal’s part to claw itself back to pre-sanctions strength,” Clemence said.

Automobile manufacturers looking to meet federal fuel efficiency requirements have driven demand for lightweight material like aluminum, creating a market gap that Kentucky has sought to fill, according to state economic development officials.

“Since the beginning of 2014, aluminum-related companies announced about 100 new facility or expansion projects in Kentucky,” Economic Development Cabinet spokesperson Jack Mazurak said. “Those projects, announced in five years, total more than $3.4 billion in corporate investment.”

Mazurak added that Kentucky has a lot riding on the Braidy project.

“Kentucky taxpayers have an additional interest in seeing Braidy Industries succeed,” he said.

Braidy expects its Atlas aluminum facility to be operational by 2021.