News

Living Wage: Ohio Valley Workers, Employers React As House Votes For $15 Minimum Wage

By: Becca Schimmel | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

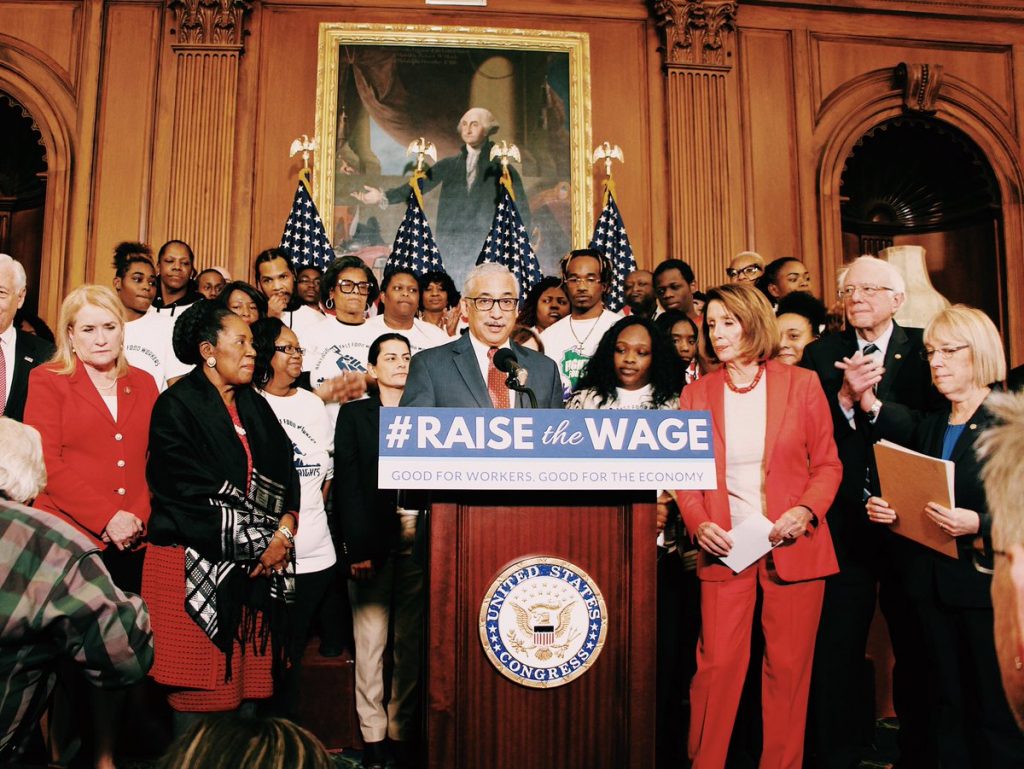

The U.S. House of Representatives voted Thursday to raise the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour, more than double the current $7.25 rate, which has not changed in a decade. The bill is unlikely to clear the Republican-controlled Senate, where Majority Leader Sen. Mitch McConnell of Kentucky has said he will not take it up.

But the vote adds energy to election-season debate about a living wage, an issue that resonates with tens of thousands in the Ohio Valley, where low-wage jobs have been taking the place of higher-earning ones lost to declines in the mining and manufacturing sectors.

Eric McIntosh is one of them.

“I’m from eastern Kentucky, I am 24, and I work for a sandwich shop for minimum wage,” McIntosh said. He lives in Morehead, in an apartment above a consignment shop. McIntosh wants to see an increase in the minimum wage, so he can live a better life and pay to attend the trade school down the road. But for now, he worries about more day-to-day concerns.

“The anxiety of poverty, you’re nervous about every single check that you get, if that’s going to be enough, and that keeps you up at night and that just makes your work even worse,” he said.

At the current minimum wage, McIntosh could still wind up well below the federal poverty level for families, even working full time.

A recent report from the Congressional Budget Office shows increasing the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour could lift about 1.3 million people out of poverty and boost the wages of 17 million workers. But the CBO also warns that such a wage hike could result in more than one million lost jobs nationwide and could diminish overall income for others.

Vicious Cycle

McIntosh described a cycle of low pay and job-related costs that keep him on a treadmill of earning just enough to keep his employment, but never enough to get ahead.

“Certain jobs require that you pay for your uniform,” he explained. But even maintaining the work uniform becomes another cost and another potential trap. “You can’t upkeep your uniform, you end up getting fired.”

He said many workers end up using high-interest, payday loan services to get by.

“But when all your money has to go to your bills, your back-pay because you had to take out a payday loan,” he said. “That’s going to all the credit at the payday loan.”

McIntosh said he’s often had to rely on others for his transportation, and he has seen his co-workers lose jobs because they couldn’t afford a minor car repair.

“And if people have more spending money, we’re going to generate more jobs,” he said. “We’re going to buy more products. I guarantee you if I made $15 an hour, I would actually buy a car for once.”

He said he would also invest in his education and work skills.

“To get ahead in life, to be able to use these jobs as a kickoff point, you have to have some money left over to be able to reinvest in yourself,” he said.

Employer Concerns

Opponents of the minimum wage increase focus on the costs to employers and the potential for job cuts. The conservative Heritage Foundation argues that small businesses would not be able to increase revenue enough to cover the cost of higher wages, and employers would be forced to increase prices or cut costs by eliminating positions.

Fred Baumann is one of those small businessmen who would be affected. He’s the chairman of the board for Baumann Paper Co., a Lexington-based company now in its third generation of Baumann family management.

“My dad started the company in 1950,” he said. His daughter now runs the business, which distributes paper, plastic and other sanitary supplies. I met him at one of the many businesses his company supplies, a hotel and restaurant.

Baumann said the company already pays many employees in the $14 to $15 an hour range. But if the federal minimum wage increases they’ll feel the pressure to increase their workers’ pay.

“We’re paying what the market demands us to pay in order to get the competent workers and to retain them,” he said.

When we first spoke Baumann didn’t know what the federal minimum wage was. He said he was under the impression that it was around $10 an hour. It is $7.25 in Kentucky. (In West Virginia it is $8.75, and $8.55 in Ohio.) He worries that a much higher wage will make workers less motivated.

“People have to have a certain amount of initiative rather than stuff being handed to them,” he said. “My perspective is, if you automatically get 15 bucks an hour, then where’s the incentive?”

He said his company would have to look at whether they’d be better off investing in more automation.

The Economic Policy Institute, a left-leaning think tank, conducted a separate analysis that questioned those job loss figures.

EPI Economist Ben Zipperer said the challenges for businesses are not as large as the “scare stories” about raising the minimum wage might have some people think. He said some of the job loss from increasing the wage can be explained by lower turnover.

“So when you raise minimum wage you actually reduce worker turnover, and makes it easier for businesses to retain workers because they’re now paying higher wages,” he said.

The CBO report also showed that it’s possible there would be no change in unemployment due to a $15 an hour minimum wage, and Zipperer said that lines up with most of the research that’s been done on the minimum wage. He said if all businesses are forced to increase the pay for their workers, it might increase a company’s ability to compete.

“It’s a lot easier for a restaurant to raise its prices a little bit when all restaurants are having to do the same thing in order to accommodate a minimum wage increase,” he said.

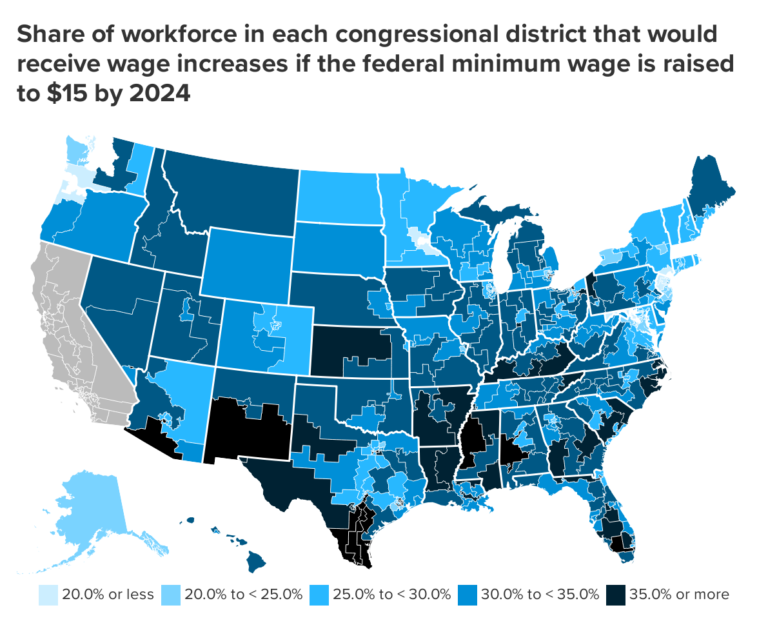

The EPA analysis also shows that the Ohio Valley region would see some of the most pronounced wage increases in the country as a result of a $15 minimum wage by 2024.

For example, the EPI report predicts that in large portions of eastern Kentucky, southern West Virginia, and southeast Ohio, roughly 40 percent of workers would see some increase in wages.

EPI says some workers employed year-round in Kentucky could see an increase in their average annual income of about $4,000. In West Virginia and Ohio, workers might see about $3,000 more in average annual income.

Zipperer said that could help offset the region’s high inequality.

“When you raise minimum wages, reduce poverty, raise family income at the bottom you’re actually reducing income inequality,” he said.

Click for an interactive map from Economic Policy Institute, which advocates for a higher minimum wage.

Rising Inequality

In late 2017, the Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights for the United Nations, Philip Alston, conducted a fact-finding tour of some places affected by extreme poverty. But those weren’t in some developing nation, they were in the United States, including a visit to communities in the Ohio Valley.

Alston’s report to the UN Human Rights Council found that of the 40 million poor Americans, more than five million live in “Third World conditions of absolute poverty.” It also showed that Americans live shorter, sicker lives than do citizens of all other rich democracies, and that the U.S. has the greatest income inequality of all industrialized nations.

The report ties those conditions to stagnated wages that force many working people to seek government assistance for food. The share of households that have a wage-earner but also receive nutrition assistance rose from about 20 percent in 1989 to more than 30 per cent in 2015.

And the report found that the average annual wage of the bottom 50 percent of earners has been stagnant since 1980.

“I wouldn’t know how to be able to explain it or show it to these people,” he said. “This is not a thing that I can reduce to words because it’s not something that I’ve had happen to me in words, I’ve had it happen to me in experience.

“I can’t make my empty stomach words for you.”