News

Coal Country: Can a Play About a Mine Disaster Help Bridge a National Divide?

By: Jeff Young | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

The actors deliver their lines from a sparse stage — just a few benches around them and 29 modest lights above. For the most part they speak directly to the audience, sharing memories of the lives of husbands, sons, fathers and nephews, some of the 29 men who died on April 5, 2010, when an explosion ripped through the Upper Big Branch Mine in West Virginia.

It’s a powerful performance, made even more so by the realization that nearly all of the actors’ dialogue is drawn directly from court transcripts and hours of interviews with about a half dozen people who lived through that tragic day and the many long days that followed.

“Coal Country,” which opened in New York’s storied Public Theater, introduced New York theater-goers to the real lives of families affected by the tragedy.

The coronavirus pandemic forced the early closure of the play. But shortly after its opening I visited the playwrights, Jessica Blank and Erik Jensen, at their Brooklyn home to learn more about their approach to documentary theater. The wife-and-husband writing duo say they hope their work will help urban audiences better understand life in the real coal country, where people have long sacrificed to help build and power America’s cities.

“I finally figured out after a couple of weeks of this, I said, ‘You know, I think that this is a community where you have to show your face,’” she said. “Just getting a phone message from some person in New York being like, ‘Hey, I’m doing a project, do you want to talk to us?’ That isn’t going to do the trick.”

So in April, 2016, she traveled to a Charleston, West Virginia, courthouse. She sat with family members of victims as Massey Energy’s former CEO Don Blankenship was sentenced for conspiracy to violate mine safety rules.

“And then I think what happened is that word got around that we were okay,” she said. “Because then we started sitting down with more and more folks.”

Blank and Jensen recorded hours of interviews during extended visits with people who had worked in the Upper Big Branch Mine and who had lost family members there. Despite being long-time New Yorkers they found an instant bond with the West Virginia families they met.

“I’m from the rural Midwest, and, you know, grew up in a small town,” Jensen said. “And so like, I immediately related to people kind of on that level.”

“Every experience we had sitting with every person we sat down with was incredibly powerful and incredibly eye opening and incredibly moving,” Blank said. She recounted learning details about long-wall mining — something she’d never heard of before — and the way that long traditions of union mining gave way in West Virginia over the past couple of decades.

“And we learned a lot about humanity, as we often do, when we do this kind of project,” she said.

Blank and Jensen have the very married couple’s habit of finishing each other’s sentences and picking up on their spouse’s thoughts. Jensen continued with the thread Blank had started.

“My thing about it was, I learned a lot about grief.” He said that during the course of the project he lost both his father and uncle. His own grief helped him relate to what people in the West Virginia community were experiencing.

“I think that was when I finally understood what we were writing. Because I multiply that by 29 and, my heart couldn’t take it,” he said. “I finally understood what it was like to be in that community, and it broke my heart open.

“And thank God for Steve’s music,” he added. “Because his songs address grief in such a beautiful way.”

Greek Chorus Of One

“Steve” is singer-songwriter Steve Earle, who sat in on some of the interviews and wrote songs which he performs to accompany the play. “Steve, to me, is the heir to Woody Guthrie,” Jensen said. “He tells real stories with his songs, you know, stories of the heart.”

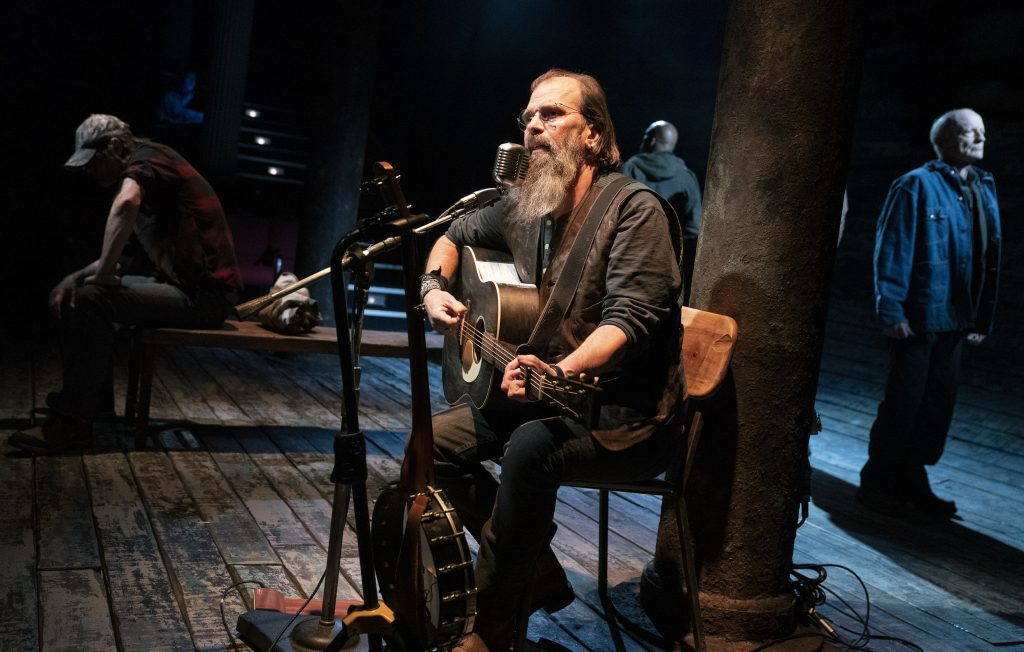

“Coal Country” is not a musical. The characters rarely sing and the songs do not propel the narrative, as in a musical. Rather, Earle sits on stage with a guitar or banjo and listens intently to the actors, then adds a song that might echo a characters’ loss or hint at deeper themes. Jensen described his role as akin to a Greek chorus of one.

“He’s there to kind of hold down the play and to orient us when we need it, or to, to break our hearts when we need that.”

In a reworking of the traditional ballad of John Henry, for example, Earle weaves in allusions to the decline of union representation among miners.

The Union come and tried to make a stand

West Virginia miners voted union to a man

You wouldn’t know it now but that was then

The Union come and tried to make a stand

I was born on this mountain, this mountain’s my home

She holds me and keeps me from worry and woe

Well, they took everything that she gave, now they’re gone

But I’ll die on this mountain, this mountain’s my home

Earle is pulling together several of the songs from “Coal Country” into a new album, “Ghosts of West Virginia,” which is scheduled for release in May.

Bridging Divides

I grew up in West Virginia, and my family roots there go back several generations. As with many West Virginia natives, I greet any outsider’s depiction of the place and its people with a degree of wariness. We’ve been burned more than a few times by hurtful stereotypes, even by those who meant well.

That is perhaps why I was surprised at my very emotional response to “Coal Country.”

[At the time I saw it, the coronavirus threat was just beginning to emerge in public awareness to the degree that I knew not to touch my face. Reader, it is hard to avoid touching your face while weeping.]

It is, of course, deeply emotional content to begin with. This is, after all, the story of one of the worst mining tragedies in recent history. But beyond that I was struck by, and grateful for, the simple details about West Virginians that Blank and Jensen recognized and relayed to their New York audience.

Their commitment to deep listening brought some deep truths to the stage.

“I think it’s our job in making this kind of work,” Blank said. “Find the people who lived that story, sit down with them, and then get out of the way.”

“Well I certainly hope,” Blank started. “It would be a privilege,” Jensen finished.

“This is a really big blind spot in communities that I move in, where people are so conscious about their politics,” Blank continued. “The things that people say sometimes about the rural working class — otherwise, really thoughtful people — are shocking to me. And I think it’s a really big blind spot that mostly comes from not having any contact with folks who come from a really different place and a really different lifestyle.”

“People have dignity, people have history,” Jensen said. “And whether you’re pro-coal or against coal, coal miners helped build this country, and they should be treated as such.”

“Built these buildings here,” Blank interjected, gesturing at the street scene outside the window.

“And right now what they’re doing is they’re blocking trains with their bodies in order to get their benefits or in order to get their last paycheck,” Jensen said. “And I just think workers should be treated better than that.”