News

As Cities Grapple With Climate Change, Gas Utilities Fight To Stay In Business

By: Jeff Brady | Dan Charles | NPR

Posted on:

FLAGSTAFF, Ariz. (NPR) — Facing the rising threat of wildfire and extreme drought, Flagstaff, Ariz., unveiled an ambitious effort two years ago to cut the heat-trapping emissions that drive climate change.

A critical part of Flagstaff’s climate plan proposed that all new construction get to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2040 and that the city promote “aggressive building electrification” to decrease reliance on fossil fuels. As in many places, buildings are a big source of Flagstaff’s greenhouse gases, mainly because many are heated by burning natural gas.

But in February 2020, the Arizona Legislature blocked much of Flagstaff’s plan for its buildings. With the backing of the state’s main gas utility, the Legislature passed a bill that prevents municipalities and counties from banning new gas infrastructure and hookups.

“It definitely put a huge hurdle in our plans for promoting electrification and fuel switching,” says Nicole Antonopoulos, Flagstaff’s sustainability director.

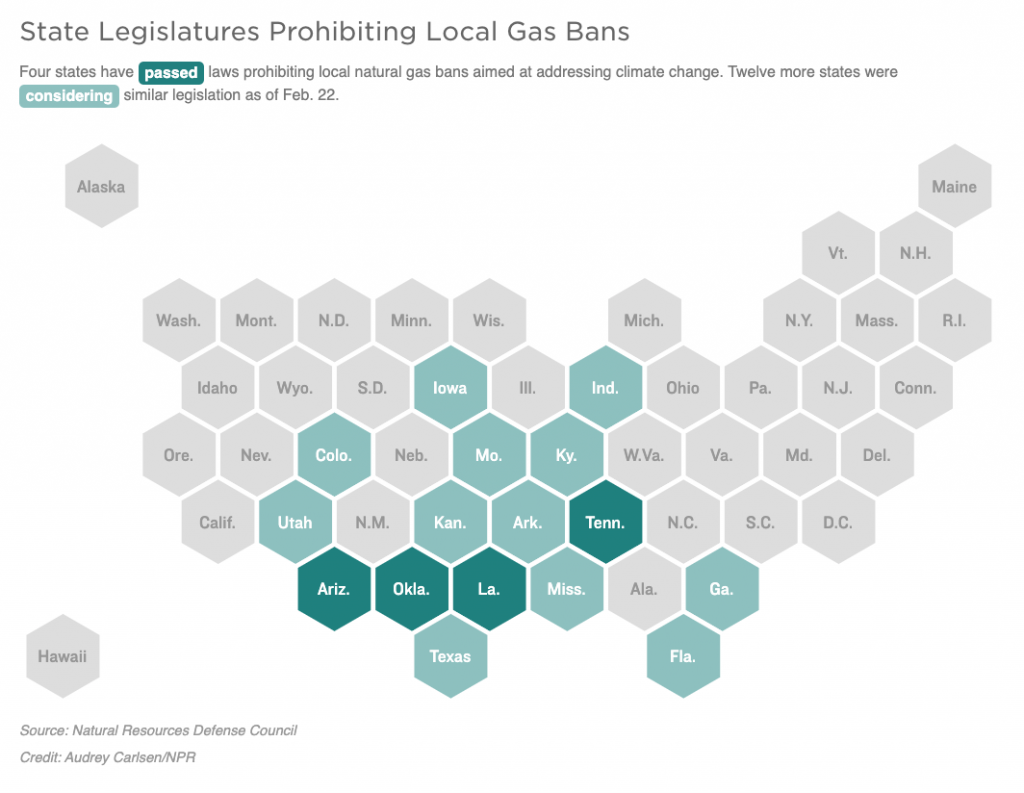

The Arizona law was a test case for a strategy the natural gas sector is now deploying nationwide. Gas utilities, with help from industry trade groups, have successfully lobbied lawmakers over the past year to introduce similar “preemption” legislation in 12 mostly Republican-controlled state legislatures, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC).

The speed and scale of the strategy show just how high the stakes are for the gas industry. According to internal reports and hundreds of recent emails obtained through public records requests and shared with NPR, the gas industry sees an existential threat in the efforts of cities, states, businesses — and now the Biden administration — to sharply reduce fossil fuel use.

“As you’re really looking at what’s going to come out of the Biden administration, they’re really talking about remaking the entire economy through a green lens, and that means eliminating natural gas,” Sue Forrester, vice president of advocacy and outreach at the American Gas Association (AGA), said during an industry conference last November.

Gas utilities and their powerful lobby, the AGA, are racing on multiple fronts to convince lawmakers and the public that swapping out natural gas with electric would harm consumers and lead to higher bills. They argue that using natural gas is compatible with addressing climate change, despite scientific evidence to the contrary.

Pro-gas groups have emerged around the country with names such as “The Empowerment Alliance” and “Partnership for Energy Progress” to sway local and state debates about electrification. The gas industry has launched ad campaigns on Facebook and Instagram touting gas as far better for cooking.

View this post on Instagram

Some industry lobbying and public relations campaigns have drawn the attention of regulators. In California, one case involved the group “Californians For Balanced Energy Solutions” (C4BES). The ratepayer advocate’s office recommended that the country’s biggest gas utility, SoCalGas, pay steep fines for improperly using ratepayer money to fund C4BES and oppose gas bans and energy efficiency measures, an allegation the company denies.

“In the broader context, this is reluctance to adapt to changing conditions. It’s a reluctance to work with the community, the state government or federal government to identify solutions to address climate change,” Antonopoulos says of the gas industry. “If they keep spending energy on preemption laws, it will distract them from identifying solutions. And that’s a missed opportunity.”

“Reframing the debate” around natural gas

State preemption laws help industries protect a particular market. These types of laws have long been used by other industries such as tobacco and plastic bag makers to kill local initiatives.

While the AGA says it “will absolutely oppose any effort to ban natural gas,” President and CEO Karen Harbert says her group maintains an arm’s length relationship with efforts to pass preemption laws. “We are not coordinating these efforts and we are not state lobbyists,” she tells NPR. “We concentrate our activities, certainly, at the federal level.”

That distinction is important because much of the AGA’s budget comes from ratepayers through its member utilities. That means you, as a ratepayer, could be funding this work, even if you don’t agree with it.

But public documents reviewed by NPR and recordings of AGA executives reveal that the group is actively involved in passing state-level bills, along with utilities and local gas trade groups, that block critical local action to cut heat-trapping emissions.

“We have run pro-gas choice legislation [in] Arizona, Tennessee, Louisiana … and Oklahoma. And so those states now, you have an option. You can’t deny someone natural gas service in their home,” the AGA’s George Lowe told colleagues during an industry conference last November. Lowe, vice president of governmental affairs and public policy, said AGA member companies were eyeing 15 to 20 other states to pass similar bills this year.

A March 2020 AGA slide presentation lists as a goal: “To keep natural gas an integral part of a clean energy future by reframing the debate.” Under “AGA initiatives,” it states: “Model and preemptive legislation — Introduced in AZ, TN, MN.”

The recordings and documents from a public records request were obtained by the Climate Investigations Center, a nonpartisan environmental watchdog group, and shared with NPR.

Harbert says gas utilities can be a part of solving the climate problem. “If the goal is to reduce emissions, we’re all in,” she says. “If the goal is to put us out of business, not so much.”

Her industry is working on cleaner alternatives, including so-called renewable natural gas. It uses waste methane from landfills and manure, and it can be mixed with hydrogen to run through the existing gas utility pipeline network. “We really have a very effective delivery system,” she says. “Whatever is going to go through that system — it could be today’s molecules or it could be tomorrow’s molecules.”

Meanwhile, she says, the industry is growing. “Natural gas utilities continue to expand and invest. We’re adding a customer every minute of every day. That means about 600,000 new customers in 2021.”

What the science requires

Over the past decade, natural gas has been credited with reducing carbon dioxide emissions. But for humanity to avoid the most catastrophic consequences of climate change, most of the world’s fossil fuels need to stay in the ground, scientists say. That includes nearly half of natural gas reserves.

Greenhouse gas emissions hit record levels in 2019 because of the expanded use of natural gas, which not only emits carbon dioxide but can leak into the atmosphere from pipelines as methane, a far more potent heat-trapping gas.

“We cannot continue using natural gas for things like heating and cooking because it’s not consistent with reaching a net-zero goal,” says Erin Mayfield, a postdoctoral research associate at Princeton University.

Mayfield co-authored a recent study into the most cost-effective ways to zero out greenhouse gas emissions. The study looked at five pathways to reach “net-zero” emissions by 2050. None of the pathways included gas utilities as they exist now.

At net-zero, heat-trapping gases would no longer build up in the atmosphere because emissions would be so low that forests or technology could remove an equal amount of them.

Other studies by the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the National Academy of Sciences echo Mayfield’s conclusion: Electrifying the country’s buildings, making appliances more efficient and powering them with renewable energy are among the best paths to cutting emissions.

“Electric heating can be totally clean … if electric utilities deliver power made from solar and wind and hydro. Which many are promising to do,” says Alejandra Mejia Cunningham, building decarbonization advocate at the NRDC.

Buildings are a ripe target for greenhouse gas cuts, accounting for about 12% of the country’s emissions. President Biden’s ambitious climate plan includes a goal to cut the carbon footprint of buildings in half by 2035 through incentives to retrofit homes and businesses with electric appliances and furnaces.

Many cities already are pushing ahead with electrification. By late January, 42 California cities had taken action to limit gas use in new buildings, according to the Sierra Club. More than a dozen of them have outright banned new buildings with gas hookups. Outside California, Salt Lake City hopes to get builders to forgo gas in new buildings through public outreach and financial incentives. Denver has a plan to electrify most buildings by 2027.

About a year ago in Arizona, Antonopoulos says, Flagstaff was considering a gas ban. “That was one of our strategies: Could we say, ‘No gas in new construction?'” she says.

At that same time, the gas utility industry was preparing its counterattack. At a December 2019 meeting of the AGA’s executive committee, Harbert called these moves by cities a new challenge to the industry.

The AGA set a 2020 priority to “expand efforts at the federal, state, and local levels to ensure policies, regulations and other initiatives include the option of natural gas for consumers and preserve customer choice of energy.”

A few months later, in February 2020, Rep. Russell Bowers, the Republican speaker of Arizona’s House of Representatives, introduced a bill blocking cities from restricting gas hookups. The bill had the backing of Southwest Gas, the state’s largest gas utility, and Bowers had received $3,500 from the company for his 2020 reelection campaign.

Republicans lined up to support the proposal. “We have been able to observe what happens in cities like Berkeley, Calif., that take these radical steps to tell people, ‘This is what you will use, whether you like it or not,'” Rep. Mark Finchem of Tucson said during a floor debate.

The bill sailed through the Legislature and was signed into law within a month. Flagstaff dropped efforts to ban new gas hookups and is trying to find other ways to get to net-zero carbon emissions.

In 2020, Oklahoma, Tennessee and Louisiana also passed preemption laws. This year, 12 states have taken up preemption legislation so far, and the chances of it passing in several are high. They include: Arkansas, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, Texas and Utah.

Many bills contain similar or even identical language. Proposed legislation in both Utah and Georgia, for instance, would block local governments from “prohibiting the connection or reconnection of any utility service based upon the type or source of energy or fuel to be delivered to any customer.”

“I didn’t dream this up,” says state Rep. Stephen Handy, R-Utah, who introduced the bill in his state. “I became aware of it, frankly, from my local natural gas supplier, Dominion.”

“We’re a little bit worried”

City officials in states considering new bills now wonder what they’ll be allowed to do if the bills pass. Jasmin Moore, sustainability director for Douglas County and the city of Lawrence, Kan., worries that her state’s proposed law, which prohibits any municipal ordinance that “discriminates against, restricts, limits, or impairs” the use of utility service, might even ban city programs aimed at promoting energy efficiency, since that would reduce gas use. “It really seems like it’s intended to slow down our progress,” Moore says.

In Utah, Salt Lake City Sustainability Director Vicki Bennett says, “We’re a little bit worried about the legislation because it’s very broad.” It’s unclear, she says, whether the proposed law in Utah would allow a city to offer financial incentives to encourage developers to go all electric.

Switching from gas to electric in existing homes can be expensive. But building new homes that are all electric can be cheaper than constructing homes with gas hookups.

At the two companies’ latest collaboration, a six-story affordable housing project in Salt Lake City, there are efficient electric heat pumps instead of gas furnaces in each unit. Heat pumps also deliver hot water.

Hollon’s company shares its blueprints and budgets with other builders. “We just want everybody to do it. It’s everybody’s air that we’re all breathing,” Hollon says. “Makes my mountain bike ride that much easier.”

The future of gas

The AGA’s Harbert warns that it’s shortsighted to eliminate gas from the country’s energy picture. “The narrative that has been set now is that we are actually the fuel of yesterday and we don’t feel that that’s the case. We believe that we’re the opportunity for tomorrow,” Harbert says.

She says abandoning gas utility infrastructure and building out the electricity grid would be expensive, something researchers with the Princeton study considered before concluding that electrification would still be necessary to keep global warming at safer levels.

Ratepayer advocates share some of the gas industry’s concerns. Stefanie Brand, director for the New Jersey Division of Rate Counsel, says a benefit of having both electricity and gas in homes is that people can still get some services when the power goes out.

“A lot of people can cook. … And a lot of people can have hot water. But think about it, when everybody drives an electric car …” Brand says you might not be able to drive anywhere when a storm knocks out the grid in your neighborhood.

Still, Brand says she understands that the country needs to reduce fossil fuel consumption and move toward more renewable energy to address climate change. That’s why she also concludes that gas utilities may not be able to stay in business.

“I do think they’re going to be around for a while,” Brand says, “but I don’t think they’re going to be around forever.”

9(MDI4ODU1ODA1MDE0ODA3MTMyMDY2MTJiNQ000))