News

Precarious rental agreements pop up where no one is looking in rural Athens County

By: Theo Peck-Suzuki | Report for America

Posted on:

AMESVILLE, Ohio (WOUB/Report for America) — Manda Gould and Shane Oswalt lived in a rental trailer on Mush Run Road for almost two decades.

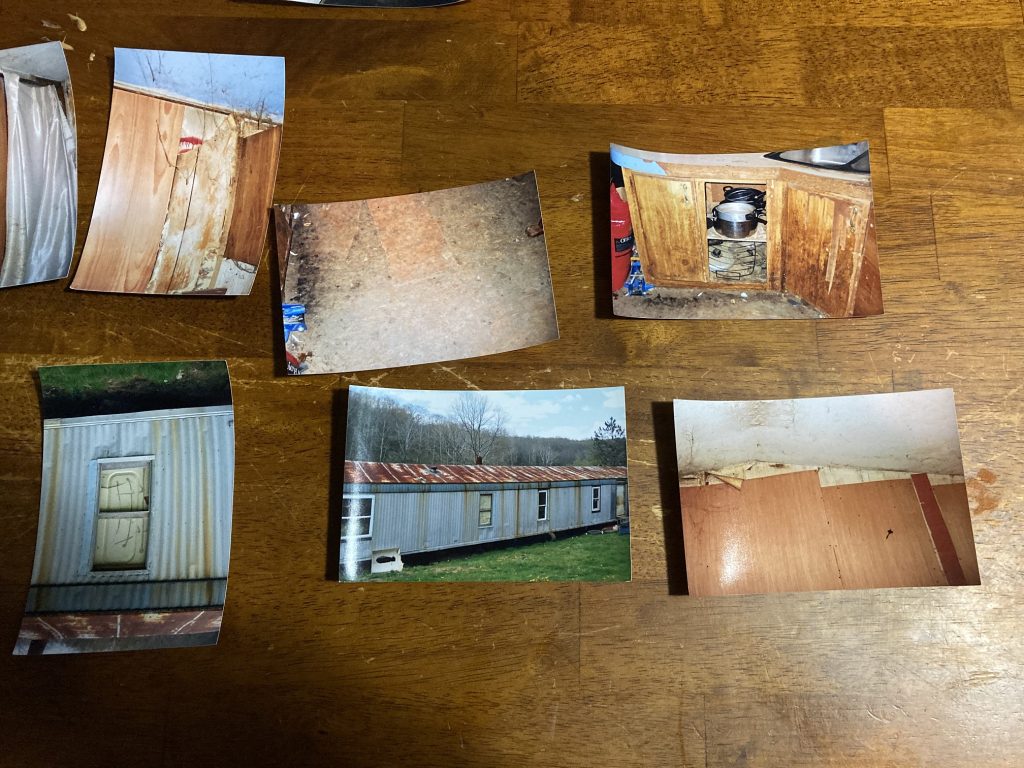

The only photos they have of that time show a badly decayed structure. There were several broken windows and exposed wiring. At one point, the hot water tank fell through the floor.

It was impossible to heat in the winter. Gould and Oswalt gathered the children in one room and used the furnace, the oven, and the dryer to stay warm. They covered the broken windows with sheets to prevent the heat from escaping and stayed up all night to keep the appliances running.

They slept while their kids were at school.

As far as Gould and Oswalt were aware, there was nowhere else for them to go. But that wasn’t the only reason they chose to remain on the property. They believed their landlord, Leonard Lucas, was planning to give them the land in exchange for Gould and Oswalt taking on maintenance responsibilities.

“He came down, talked to us, saying, you guys want to buy this trailer,” Gould recalled. “I’ll let you guys buy it and let you guys have the title. And after you guys get the trailer in your name, then I’ll let you own the land.”

The problem with land contracts

There’s no written record of any property transfer arrangement between Lucas, Gould and Oswalt. But these types of offers — often called “work-to-own” or “land contract” agreements — are not unheard of in rural Southeast Ohio, where regulatory agencies are almost nonexistent and housing is scarce.

“They’re usually just a scheme for bad landlords,” said Zack Eckles of the Ohio Poverty Law Center. “There are good landlords out there, but generally, (they’re) a scheme for bad landlords to be able to collect rent from their tenants while also having tenants take on the responsibility of maintaining the property.”

There is a legal process for transferring ownership of a property through land contract. However, Eckles said it rarely works out that way for tenants.

“Landlord generally evicts tenant prior to them ever being able to reach that option,” he explained.

And if there’s nothing in writing, then nothing can be proven in court.

School outreach worker Becky Handa has also seen a number of land contracts among the families she works with. Her observations mirror Eckles’.

“Part of the catch is the families are responsible for the upkeep, because essentially, they believe it’s going to be their home,” she said.

“If there is a missed payment because they are trying to do repairs, then they’ll get an eviction notice,” she added. “And everything they’ve put in is no longer — that somehow breaks this contract that they have. Then the next person moves in, and it starts all over again.”

In the case of Gould and Oswalt, their landlord did sign the trailer over to them in 2008. It’s unclear how far the structure had deteriorated by then. He never signed over the land.

Leonard Lucas passed away in 2019. His daughter Deborah doubts he ever agreed to such a deal, as he never sold property. She said her father only gave away the trailer because Oswalt damaged it by trying to renovate it without permission.

Oswalt denies that.

In any case, signing over the trailer released Lucas from his statutory obligation as a landlord to keep it maintained. Meanwhile, Gould and Oswalt continued paying him rent for the lot.

An unregulated rental market

County Commissioner Chris Chmiel said he believes land contracts are “horrible” but acknowledged the county doesn’t currently have many tools to address the issue.

That could change, if there were more political will for it.

“It’s not something I hear a lot of people talking about,” said Chmiel.

Zoning and code enforcement are regulatory tools that can compel landlords to maintain properties themselves. This can potentially reduce the incentives for arrangements like land contracts.

“After zoning, you’ll get building codes, building inspection, electrical inspection, plumbing inspection,” explained Patrick McGarry, director of environmental health at the Athens City-County Health Department.

But there is no zoning in the rural parts of Athens County. The only regulations are those enforced by the health department, and its power is limited.

“Our authority is, we have to have a complaint filed because we don’t have right of entry onto properties,” said McGarry.

However, many tenants don’t want to complain. They fear their landlord might retaliate by evicting them or deciding not to renew their lease. Many are on oral month-to-month leases, which landlords can terminate at the end of the month. And the lack of low-income housing means they may not have anywhere else to go.

Even if a complaint is filed, there’s only so much the health department can do.

“We don’t have the authority to do building inspections, structural inspections, plumbings,” McGarry explained. “I don’t have any employees that have those qualifications.”

His employees can, however, make referrals if they see an “egregious” violation.

The path to moving out

By 2015, the trailer Gould and Oswalt were living in had deteriorated severely. That’s when Gould met Becky Handa, who was then working at Amesville Elementary.

Handa said she realized immediately that the family needed to move.

“It really should have been condemned,” she recalled. “It wasn’t livable.”

She found that Gould and Oswalt were strong candidates for building a home through Habitat for Humanity. But Gould and Oswalt were initially hesitant. They still believed they would one day own the property the trailer was on.

It took Handa some time before she finally convinced them to leave. Throughout the construction process, she picked Gould and Oswalt up and drove them to the site of their home-to-be.

“Felt like a home,” Oswalt said of his feelings when they entered the finished house.

They still live there today.