Communiqué

An unlikely collection of Americans start a movement that rescues THE AMERICAN BUFFALO. Ken Burns’ finale on Nov. 14 at 9:00 pm

< < Back toNEW KEN BURNS FILM EXPLORES HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN BUFFALO

Two-Part, Four-Hour Film Traces the Near Demise – and Ultimate Return – of the U.S. National Mammal, While Examining the Species’ Connection to Indigenous Communities and the Land

Commentary and Perspectives Provided by Authors N. Scott Momaday, Steven Rinella and Michael Punke; Historians Sara Dant, Rosalyn LaPier, Dan Flores and Elliott West; and Tribal Nation Members George Horse Capture, Jr., Marcia Pablo, Gerard Baker and Dustin Tahmahkera, Among Others

THE AMERICAN BUFFALO, a two-part, four-hour film directed by Ken Burns.

Finale: Thursday, November 14 at 9:00 pm

“Into The Storm”

By the late 1880s, the buffalo that once numbered in the tens of millions is teetering on the brink of extinction. But a diverse and unlikely collection of Americans start a movement that rescues the national mammal from disappearing forever.

THE AMERICAN BUFFALO is the biography of an improbable, shaggy beast that has found itself at the center of many of the country’s most mythic and heartbreaking tales. The series, which has been in production for four years, will take viewers on a journey through more than 10,000 years of North American history and across some of the continent’s most iconic landscapes, tracing the mammal’s evolution, its significance to the Great Plains and, most importantly, its relationship to the Indigenous People of North America.

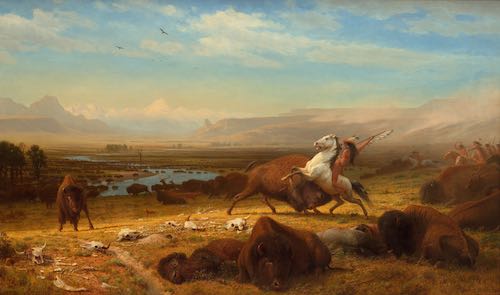

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

“It is a quintessentially American story,” Ken Burns said, “filled with unforgettable stories and people. But it is also a morality tale encompassing two historically significant lessons that resonate today: how humans can damage the natural world and also how we can work together to make choices to preserve the environment around us. The story of the American buffalo is also the story of Native nations who lived with and relied on the buffalo to survive, developing a sacred relationship that evolved over more than 10,000 years but which was almost completely severed in fewer than 100.”

The series was written by Dayton Duncan (COUNTRY MUSIC, THE DUST BOWL, THE NATIONAL PARKS, LEWIS & CLARK), who is also the author of the companion book, “Blood Memory: The Tragic Decline and Improbable Resurrection of the American Buffalo,” to be published by Knopf timed to the broadcast. It was produced by Burns’s longtime colleague Julie Dunfey (COUNTRY MUSIC, THE NATIONAL PARKS, THE DUST BOWL, THE CIVIL WAR). Julianna Brannum (CONSCIENCE POINT, NATIVE AMERICA, WE SHALL REMAIN “Wounded Knee”), a member of the Quahada band of the Comanche Nation of Oklahoma, served as consulting producer. W. Richard West, Jr., a Cheyenne and founding director and director emeritus of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian, was the senior advisor.

For thousands of generations, buffalo have evolved alongside Indigenous people who relied on them for food and shelter, and, in exchange for killing them, revered the animal. The stories of Native people anchor the series, including the Kiowa, Comanche and Cheyenne of the Southern Plains; the Pawnee of the Central Plains; the Salish, Kootenai, Lakota, Mandan-Hidatasa, Aaniiih, Crow, Northern Cheyenne and Blackfeet from the Northern Plains; and others.

The film includes interviews with leading Native American scholars, land experts and Tribal Nation members. Among those interviewed were Gerard Baker (Mandan-Hidatsa), George Horse Capture, Jr. (Aaniiih), Rosalyn LaPier (Blackfeet of Montana and Métis), N. Scott Momaday (Kiowa), Marcia Pablo (Pend d’Oreille and Kootenai), Ron Parker (Comanche), Dustin Tahmahkera (Comanche) and Germaine White (Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes).

“The story of American bison,” historian Rosalyn LaPier says in the film, “really is two different stories. It’s a story of Indigenous people and their relationship with the bison for thousands of years. And then, enter not just the Europeans, but the Americans…that’s a completely different story. That really is a story of utter destruction.”

THE AMERICAN BUFFALO documents the startling swiftness of the species’ near extinction in the late 19th century. Numbering an estimated 30 million in the early 1800s, the herds began declining for a variety of reasons, including the lucrative buffalo robe trade, the steady westward settlement of an expanding United States, diseases introduced by domestic cattle and drought. But the arrival of the railroads in the early 1870s and a new demand for buffalo hides to be used in the belts driving industrial machines back East brought thousands of hide hunters to the Great Plains. In just over a decade the number of bison collapsed from 12-15 million to fewer than a thousand, representing one of the most dramatic examples of our ability to destroy the natural world. By 1900, the American buffalo teetered on the brink of disappearing forever, and the Native people of the Plains entered one of the most traumatic moments of their existence.

But the other, lesser-known part of this story, told in the film’s second episode, is about the people who set out to save the species from extermination and how they did it. Their actions provide compelling proof that we are equally capable of pulling back from the brink of environmental catastrophe if we set our minds to it.

Both parts of the larger narrative are filled with unforgettable stories and people, including Old Lady Horse, a Kiowa woman who describes her tribe’s spiritual and practical relationship with the bison, and Charles Jesse “Buffalo” Jones, a mercenary hunter who took part in the elimination of 3 million buffalo, then turned to rescuing motherless calves and starting a small herd that would eventually provide seed stock for others. The eloquent words of Pretty-Shield, a Crow medicine woman, describe the utter devastation felt by all the tribes at the destruction of the great herds, while crusading conservationist George Bird Grinnell’s editorials explore how central Yellowstone National Park’s small herd became to the survival of the species.

The buffalo were brought back from the brink of extinction by a diverse and unlikely collection of Americans, such as Native American families on reservations in South Dakota and Montana, the legendary cattleman Charles Goodnight and his wife Molly in the Texas Panhandle, and Austin Corbin, the Long Island railroad magnate who owned an exotic game preserve in New Hampshire. There was also Ernest Harold Baynes, an eccentric nature writer, who trained a pair of young bison bulls to pull a wagon and took them on tour to help launch a national movement to save the species. Other, more famous champions of the movement included the Bronx Zoo’s William T. Hornaday; William “Buffalo Bill” Cody; and Theodore Roosevelt, who hurried west as an impulsive young man to shoot a bison before they were all gone, and then, as president of the United States, created the first federal bison reserves in the West. The film also introduces Quanah Parker, the Comanche leader who went from waging war against the U.S. Army and the hide hunters to a man of peace, who lived to see the buffalo return to his homeland.

Credit: Smithsonian American Art Museum

Today, there are approximately 350,000 buffalo in the U.S., most of them descendants of 77 animals from five founding herds at the start of the 20th century, and their numbers are increasing. THE AMERICAN BUFFALO concludes with a brief look at some of the ongoing restoration efforts and the central role the Tribal Nations have had in their return.

Voice actors in the film are Adam Arkin, Tantoo Cardinal, Tim Clark, Tokala Clifford, Jeff Daniels, Hope Davis, Paul Giamatti, Murphy Guyer, Michael Horse, Derek Jacobi, Gene Jones, Carolyn McCormick, Craig Mellish, Jon Proudstar, Chaske Spencer and Richard Whitman.

THE AMERICAN BUFFALO is a production of Florentine Films and WETA Washington, D.C. Directed by Ken Burns. Written by Dayton Duncan. Produced by Julie Dunfey and Ken Burns, and co-produced by Susan Shumaker. Emily Mosher served as associate producer and Julianna Brannum as consulting producer. Edited by Craig Mellish, ACE; Alex Cucchi, assistant editor. Principal cinematography by Buddy Squires. Narrated by Peter Coyote. The executive in charge for WETA is John F. Wilson. Executive producer is Ken Burns.