News

Hopewell Health Centers lays off 35 employees because of drug manufacturers’ restrictions on a little-known federal program

By: Theo Peck-Suzuki | Report for America

Posted on:

ATHENS, Ohio (WOUB/Report for America) — Being on Hopewell’s RN care management team was Erin Eddleblute’s dream job.

“We were kind of — and this was how our boss referred to it and I loved it — the junk drawer of Hopewell,” Eddleblute said.

She and the other RN care managers would work one-on-one with clients on all manner of issues. One client had blood sugar in the 600s every day; with Eddleblute’s help, he discovered he’d been using his diabetes medication incorrectly.

“After a year of working with me, he’s finally able to have a normal blood sugar and have a normal, normal-ish life,” Eddleblute said.

Much of what the RN care management team did involved helping people with daily life. They took walks with clients and connected them with Hopewell’s wellness program, which distributed fresh produce to those who couldn’t otherwise access it. The team was small — just six people — but Eddleblute said their impact was large. Eddleblute estimates she saw around 250 people a year.

And then, suddenly, it was all over.

In late August, Hopewell administrators abruptly informed the RN care management team that the program was being cut due to a major budget shortfall. The wellness team was also laid off, along with a recently opened child crisis stabilization unit in Gallia County and a handful of other positions. The total layoffs amounted to 35 people.

“It was just really a punch to the gut,” Eddleblute said.

What Eddleblute didn’t understand was that the loss of her job was the direct result of a national sparring match between drug manufacturers and the beneficiaries of an obscure, but vital, initiative called the 340B Drug Pricing Program, which provides medication at a discount for vulnerable populations. The battle had played out far, far away from Eddleblute’s day-to-day life. Now, she was paying the cost.

Hopewell CEO Mark Bridenbaugh declined an interview for this story. However, in a news release he wrote that Hopewell was facing a $2.5 million shortfall due to an “attack” on 340B. Drug manufacturers have placed steep restrictions on this program, Bridenbaugh wrote, eating into Hopewell’s budget and compelling the organization to cut staff.

An internal budget document from Hopewell appears to support Bridenbaugh’s explanation. It shows that Hopewell’s annual revenue from 340B has decreased by about $2.5 million since 2019. While other revenue sources have gone up during that time, expenses have risen faster, particularly for personnel. Hopewell was already $1.2 million in the red in 2023. The document did not include information for 2024.

“You know, it was just like, ‘Why? Why are we in this financial crisis?’ Because we’re busy. I don’t — I still don’t understand, and I keep racking my brain, like, why were we? Because we were busy,” Eddleblute said.

Other Hopewell employees shared Eddleblute’s bewilderment. One employee, who declined to share their name to avoid compromising their work, said the loss of the RN care management and wellness teams dealt a major blow to morale.

“Internally, of course, folks are deeply frustrated, concerned about their colleagues that they’re losing, but also not sure what happens next for some of our clients,” the employee said.

“There’s a good chance that in some of our clients, we may see regression. We might see them stall or plateau in their progress. The lack of (wellness) groups in particular — the walking group and the yoga group were not only helpful to our clients to build some more physical fitness or wellness … into their lives, but also got them out of being isolated,” the employee said.

That concern weighs on Eddleblute, as well.

“One of my patients said, ‘What am I gonna do? You always have the answer, Erin.’ And I said, ‘I don’t right now,’” she said.

What 340B is and why it matters

Just north of Hopewell’s service area is Muskingum Valley Health Centers. Like Hopewell, Muskingum Valley is a federally qualified health center, also known as an FQHC. As a safety net provider, its mission is to serve vulnerable populations, and the 340B program is a key part of that, according to Muskingum Valley CEO Dan Atkinson.

“It was enacted in 1992 by Congress, and essentially, what they were seeking to achieve was to work with drug manufacturers to say, hey, in exchange for us covering your medications through Medicaid and Medicare … we need you to also provide front-end discounts for coverage,” Atkinson said.

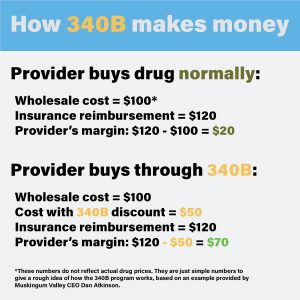

Here’s what that actually looks like:

Let’s assume insurance normally reimburses a provider $120 for this $100 medication. This way, the profit margin for the provider is $20. Under 340B, insurance is still required to reimburse the full $120 — even though Muskingum Valley only paid (in this example) $50. That creates a $70 margin for Muskingum Valley — a much higher profit.

And that’s the point, according to Atkinson.

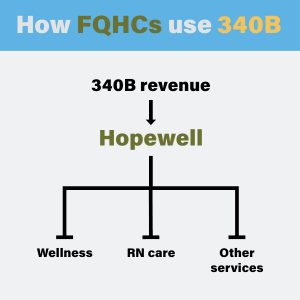

“We take those dollars and reinvest them in services for patients. And a lot of times, it could be services that would not be possible for us to even offer, or services that we can’t get reimbursed for,” he explained.

Put another way: Much of the work FQHCs do loses money. That’s the nature of caring for vulnerable, low-income populations. With 340B, FQHCs generate a profit they can reinvest in other things — like, say, RN care management or a wellness program.

Pharmaceutical companies push back

Atkinson said the problem picked up around the pandemic.

“What pharmaceutical companies started doing is they started restricting the number of contract pharmacies that they would ship 340B medications to,” he said.

As it turns out, this is a huge problem for FQHCs.

“If you don’t own and operate your own pharmacy, you contract with pharmacies in your local market to distribute these medications to your patients,” Atkinson explained.

Now, drug manufacturers like Eli Lilly and AstraZeneca are saying FQHCs can’t do that anymore. An FQHC may be forced to choose one pharmacy in its entire service area to receive those companies’ drugs.

“That could require a patient who lives in Malta, Ohio, to travel to Coshocton, Ohio, to get their medication,” Atkinson said. The trip is about 60 miles.

This is a problem for many low-income patients, who may lack reliable transportation or the freedom to take time off work. In some cases, they may have to go without life saving medication. And it’s a problem for FQHCs, who are losing revenue because they sell fewer drugs with that big 340B margin.

“We’re seeing this shift in (340B where) most of the sales are going to hospitals, and predominantly really big hospitals,” Longo said. “These 340B hospitals buy most of the medicines at … the low price, the 340B price, but then they go ahead and mark up the price of the medicine. … So they’re buying low through 340B, selling super high, and a patient’s cost sharing is based on that higher price.”

Longo said no one is accusing FQHCs of doing this.

“Those are true safety net entities,” she said. “We know they are often on tighter budgets. They’re the types of entities that should be in this program, and we want to make sure the program works for them.”

These big hospitals are a different kind of 340B covered entity. Longo said they are often located in more affluent areas and provide below-average levels of charity (free or reduced-cost) care for their communities.

“There’s a disconnect there,” she said.

The pharmaceutical industry isn’t alone in raising concerns about the 340B program as a whole. The U.S. Government Accountability Office issued a report in 2018 identifying multiple weaknesses in the program’s federal oversight and offering solutions. The agency in charge of the program has concurred with some, but not all, of the office’s recommendations.

Longo said the big hospitals’ use of contract pharmacies to distribute 340B medications is exacerbating the problem.

“More than half of the time, a patient that goes to a pharmacy that is a contract pharmacy, they are charging that patient full price for the medicine. They’re not giving the discount,” she said.

Longo said this is why drug manufacturers have started limiting how many contract pharmacies a 340B covered entity can use. However, this doesn’t explain why some manufacturers are willfully extending those limits to FQHCs — something they could choose not to do, according to Julie DiRossi-King, president and CEO of the Ohio Association of Community Health Centers.

DiRossi-King said initially, the drug manufacturers’ restrictions seldom included FQHCs. That’s no longer the case.

“More and more, it’s regardless of what type (of entity) you are,” DiRossi-King said.

Atkinson expressed a similar frustration. He noted that FQHCs have stricter guidelines on using 340B than some other covered entities.

“I’ll be the first one to say that we’re all about improved transparency, and we believe that reform is necessary. But I think that that’s where we need to focus our time and attention and stop with the restrictions that are basically loopholes in the law,” he said.

Longo said her organization has partnered with FQHCs on federal legislation that would revamp 340B and, in doing so, solve the contract pharmacy problem. In the meantime, DiRossi-King said the state of Ohio is considering its own legislative remedy through a pair of companion bills: HB 588 and SB 269.

These bills would prohibit drug manufacturers from imposing limits on 340B contract pharmacies, according to DiRossi-King.

The bottom line

Without a legislative fix, there isn’t much FQHCs can do to protect their bottom lines from the restrictions drug companies have placed on the 340B program. Their only option, DiRossi-King said, is to build and operate their own in-house pharmacies. These aren’t subject to drug manufacturers’ restrictions, but such a project isn’t easy.

“That takes energy, time, funding and space,” DiRossi-King said. “I mean, we don’t just have exam rooms not being used or that you could make into a pharmacy.”

The strategy did prove effective for Muskingum Valley Health Centers, though. The organization opened two in-house pharmacies at precisely the same time the restrictions started eating into its income, creating a crucial new revenue stream.

“If we were not successful in timing that, I’m confident we would have had to cut multiple programs,” Atkinson said.

Still, not everyone can do what Muskingum Valley did.

And, he noted, two pharmacies still aren’t enough to meet the needs of everyone in Muskingum Valley’s 2,100-square-mile service area.

Meanwhile, back in Athens County, Erin Eddleblute is spending much of her time taking care of her mother, who has dementia. She still keeps in touch with her former colleagues from RN care management — a group she describes as her “dream team.”

“We all keep switching job sites back and forth and … just making sure we’re all OK, ’cause none of us are really doing really well mentally right now,” she said.

And of course, she’s wondering what comes next.

“Do I go back to hospital life? … Do I want to go back to that life where (I’m) missing my kid’s sports, missing my kid doing things, not being there for my dad and my mom, who need me the most right now?” she wondered. “I’m kinda being picky about jobs, trying to find the right fit, and it’s sad because I feel like I lost my dream job.”

She added, “It’s hard to go backwards when you had your dream.”