News

Ohio’s psychiatric hospitals are nearly full. What can the state do?

By: Kendall Crawford | The Ohio Newsroom

Posted on:

CINCINNATI (The Ohio Newsroom) — Ohio’s six state-run psychiatric hospitals are nearly full. Their patients are almost exclusively individuals coming from the criminal justice system – including those transferred from jails, those found incompetent to stand trial and those found not guilty by reason of insanity.

Criminal-justice involved individuals often stay for an average of six months of care. With the hospitals at 96% capacity, those who need psychiatric care face long waitlists.

“For individuals who are criminal justice-involved, this may mean waiting in the jail where they are awaiting trial,” said LeeAnne Cornyn, director of the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction services.

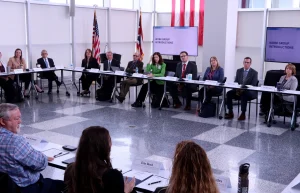

The state is working to address this intersection of mental health and criminal justice. Governor Mike DeWine convened a working group of judges, mental health experts and law enforcement earlier this year, with the hopes of helping Ohio increase both its community-based and state-run care options for those suffering from behavioral health issues.

They issued a report detailing 15 recommendations for how the state can increase services. Here’s some of the top takeaways:

1. Creating more beds in psychiatric hospitals

While it may seem obvious, Cornyn said expanding the state’s psychiatric capacity means adding more beds. Ohio’s six facilities have around 1,100 beds while Ohio is home to more than 11 million people.

“Ultimately, that will add a little more than 200 additional beds to our state system,” Cornyn said. “But that’s a few years down the road until we can get those beds filled.”

In addition, the state will continue its Hospital Access Funds program, which allows those not involved with the criminal justice system to have their care covered at a private psychiatric facility.

2. Catch behavioral health issues earlier

While increasing capacity is an important step, Cornyn said it won’t fix the state’s problem. To do that, Ohio also needs to invest in prevention services and community-based care options.

“We only want an individual to have an inpatient stay if they absolutely need it. So we need to build up more community capacity to ensure that we are serving Ohioans in the least restrictive environment possible,” Cornyn said.

That means bringing more behavioral health programs to schools and combating housing insecurity. Cornyn said the state’s current crisis intervention programs also need to be bolstered, including the state’s 988 suicide hotline and its mobile response and stabilization services (MRSS).

“If we’re waiting until an individual is so progressed in their illness that they are in need of services in one of our state psychiatric hospitals, then we’ve missed a lot of opportunities to deliver treatment and to intervene early,” Cornyn said.

3. Implement pre-trial diversion programs

The working group also suggested implementing more programs that allow some offenders to avoid the traditional criminal justice system, in favor of behavioral health treatment. The 30-day pilot programs could reduce recidivism and the need for hospitalizations by the state.

OhioMHAS will work with criminal justice partners across the state to establish a new pre-trial mental health diversion pathway in the Ohio Revised Code.

“There is an increase in individuals coming into the criminal justice system that have behavioral health conditions, whether that is substance use disorder, mental illness or both at the same time,” Cornyn said. “And it makes it very difficult for our staff in jails to do their jobs.”

4. Expand jail-based programs and services

With so many individuals in the carceral system needing psychiatric care, Cornyn said the state’s jails should equip themselves to meet behavioral health needs.

“Not always are these two professions using the same terminology, speaking the same language, and that can create some barriers for individuals who are impacted by those systems,” Cornyn said.

On the state level, Cornyn said the group recommends expanding Ohio’s jail medication reimbursement program. Jails often use medication to stabilize people with behavioral health issues. They can apply to use part of the state’s $5 million fund to cover the cost of some opioid use disorder and psychiatric medication.

It’s in demand, Cornyn said. The program has more applicants than it can serve.

“These are programs that can help an individual get the care and the treatment that they need right there in the jail,” Cornyn said. “It can help stabilize them so that they don’t even need to come into one of our state psychiatric hospitals for competency restoration.”