Theresa Fogel and her daughters, Rylenn (right) and Everly. Theresa refers to Rylenn as her “little helper.” [Photo courtesy of Theresa Fogel]

Chapter 4

Rylenn and Everly

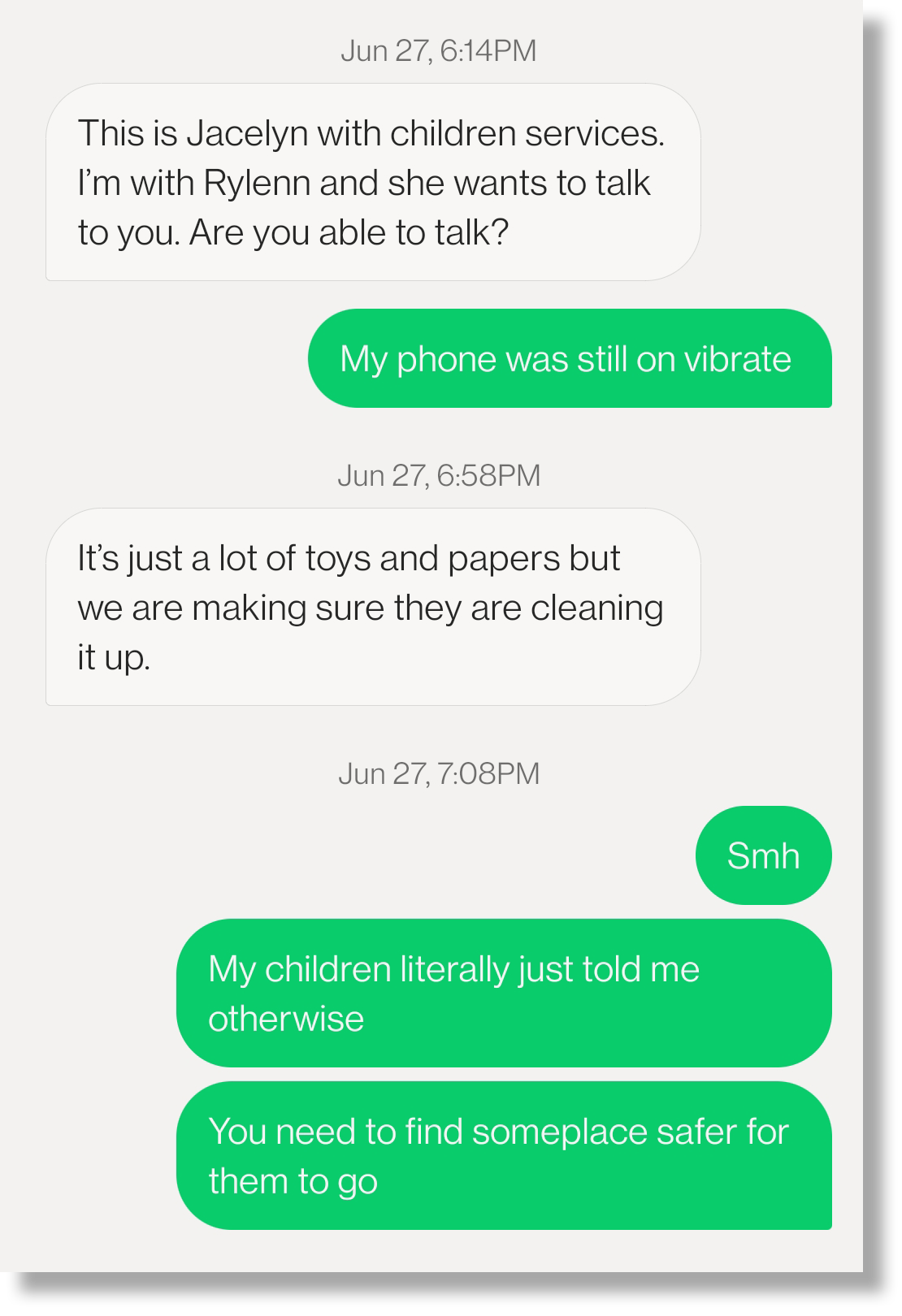

The evening of June 27, Theresa got a text message from Jacelyn McGaughey, the Athens County Children Services caseworker who had taken her children. The girls had just arrived at a foster home in Zanesville, one hour north of Glouster. Theresa’s older daughter, Rylenn, wanted to speak with her mom.

McGaughey put Theresa on speaker phone. It was the first time Theresa had heard from any of her children in two days.

“I heard Rylenn saying it smells really bad in here, like cat pee,” Theresa recalled.

That was the first red flag.

Theresa’s teenage sons, Azriel and Josiah, were in the home with them. McGaughey was taking the boys to their aunt’s house in Butler County next.

“I’m like, ‘Azriel, are the conditions of this house a place I would leave you or let any of you spend the night at?’” Theresa recalled. “He says, ‘No, but if it gets cleaned up, I guess.’ And I’m like, ‘Cleaned up? What’s wrong with the conditions of this house?’”

Azriel confirmed what Rylenn had just said. It smelled like cat pee. There were spots all over the carpet. There were papers and garbage and toys everywhere. The only clean room was the one the girls would be sleeping in.

Even Josiah was unimpressed. Theresa could hear him in the background. He said it wasn’t a place Theresa would ever let them stay.

Theresa asked McGaughey if the foster parents had known Rylenn and Everly were coming. Before McGaughey could answer, she heard Josiah say no.

“And then, over top of him, she (McGaughey) goes, ‘Well, they knew we were coming. They just didn’t know what time,’” Theresa recalled.

“I said, well, it’s seven o’clock at night. I’m pretty sure if they knew my kids were coming, they had all day to clean that house.”

She told McGaughey to find another place for her kids to go.

McGaughey responded that she would contact her supervisor. Later, she texted Theresa to say that the mess was just toys and papers. They would make sure the family cleaned everything up.

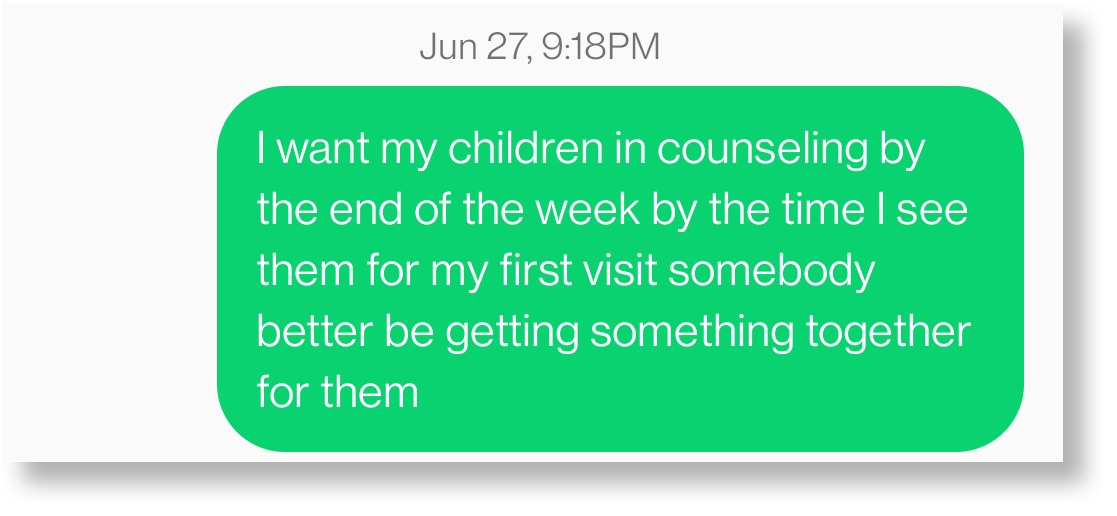

Theresa replied that she wanted her children in counseling by the end of the week. She could hear quite clearly that they were upset.

Part of a text exchange between Theresa and caseworker Jacelyn McGaughey about the first foster home where Theresa’s daughters were placed.

A few days later, Theresa’s mother, Cheryl Boger, called Athens County Children Services to share her own concerns about the girls. A caseworker — it’s not clear who — told Cheryl the girls were fine and said Cheryl should be happy knowing they were safe, now that they were not with their mother.

Bruises

Bad news continued to flow out of the foster home in Zanesville. The foster mother told Cheryl that Everly had been throwing up and was spending most of the day in bed. Cheryl shared this with Theresa, who reported it to McGaughey. According to Theresa, McGaughey told her it wasn’t true and that Everly was fine.

Rylenn’s friend Xavier and his mother, Sue McGee, also had a chance to speak with Rylenn on the phone. She told McGee the same things Theresa was hearing. She said the foster parents were strict about what they could eat. Once, 4-year-old Everly couldn’t find her shoes when the foster mother wanted to go out, and the foster mother threatened to leave her behind if she didn't hurry up.

Rylenn also said the foster parents had a son who picked on her and Everly frequently and hit them with his tablet. At one point, he even threatened to throw them down the stairs.

When the girls were first taken, McGee had promised Rylenn that everything would be OK. Now, those words weighed on her.

“I felt horrible,” McGee said. “After telling her that, I just felt horrible.”

McGee called Children Services to ask if the girls could be placed with her. No one called her back.

The agency gave Theresa one supervised visit with the girls a week. At the second of these visits, on July 8, Theresa noticed Rylenn had a bruise on her arm. Rylenn told her the foster parents’ son had hit her with the tablet again. Theresa pressed her daughter for details, but the visit supervisor told them they had to change the subject.

“‘Rylenn, we can’t talk about that, you’re going to have to change the subject,’” Theresa recalled the supervisor saying.

“I’m like, how is my daughter supposed to tell me if she’s OK or not?”

Things came to a head the following week. Theresa had brought food to eat with the girls.

“It was as soon as I got there,” Theresa recalled. “We were sitting on the floor, before we had even started eating, and I’m like, ‘Everly, what happened to your legs?’ I’m talking, bruises this big around on my 4-year-old’s legs, yellow and black. And then I look at her, and there’s another big one right here, same spot on the other leg.”

“And I’m like, ‘Rylenn, what happened to your sister’s legs?’ And when Rylenn turns her head, she’s got a big old mark by her ear, right here. And I’m like, ‘What happened to Sissy’s legs?’ And she keeps going — Now, you’re the visit supervisor, right? Me and my kids are sitting on the floor. She’s looking up, looking at me, looking at Everly, looking over — ‘Everly got thrown off the top of a slide … .’ And then looks over at that lady. And I’m like, ‘What?’”

Theresa brought the girls into the bathroom with her. It was the one place she knew they wouldn’t be watched and could talk freely.

Once they were in the bathroom, Rylenn’s demeanor changed.

“Rylenn then whispers in my ear and says, ‘Mommy, I’m scared. Please, please don’t make us go back,’” Theresa recalled. “She says, ‘Please don’t make us go back to this foster home. Please Mommy, don’t make us go back there. They’re so mean to me and Everly and we don’t feel comfortable there. Please, Mommy. Please.’ Whispering this in my ear. And I’m not allowed to even react, because I can’t walk out of the bathroom like that. Then they’re gonna not let me take my kids to the bathroom.”

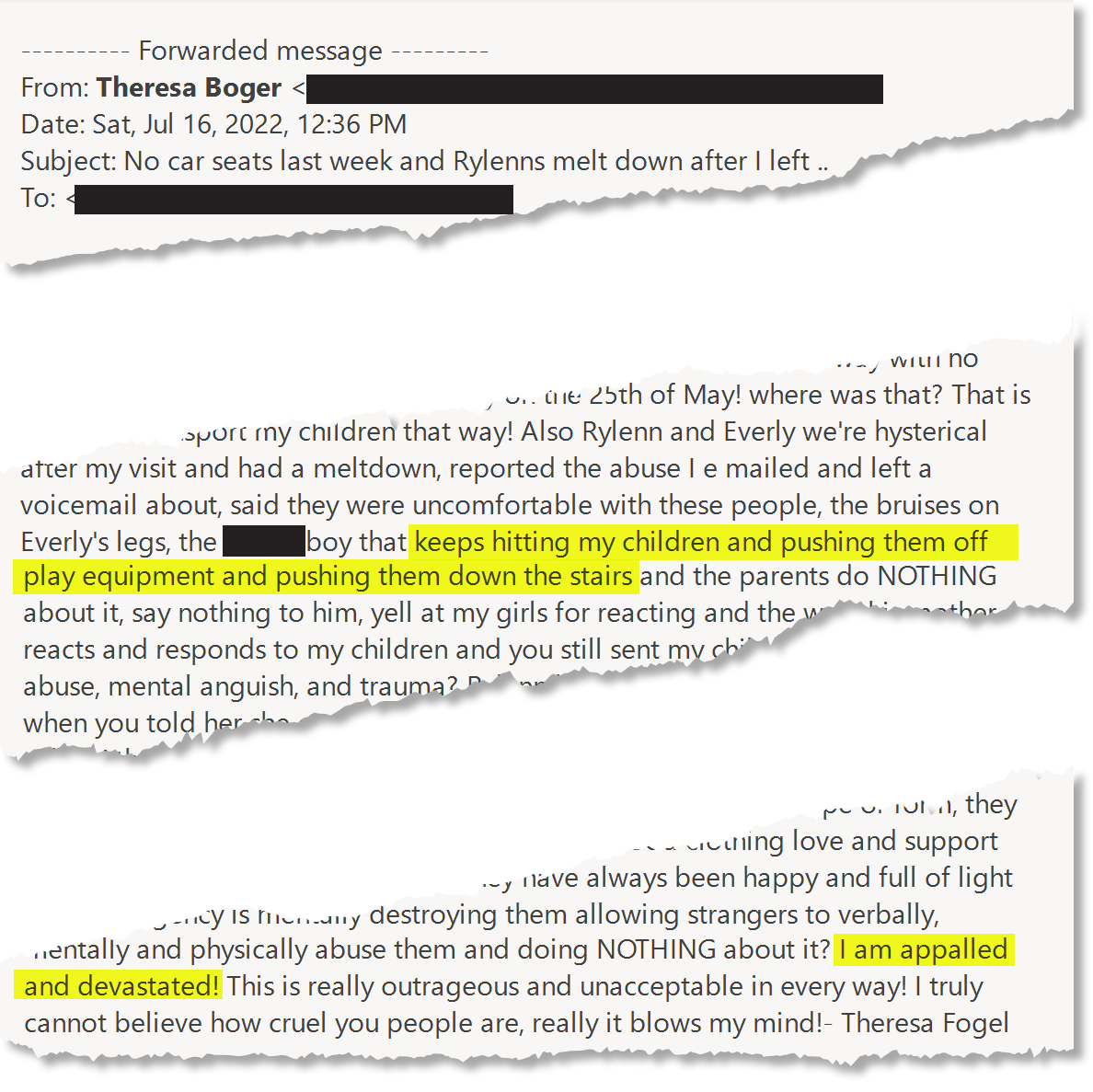

Theresa had to leave the girls with Children Services. There was nothing she could do to stop them from going back. She sent an angry email to McGaughey explaining her frustrations.

“Rylenn and Everly were hysterical after my visit and had a meltdown,” she wrote before a lengthy explanation of the issues at the foster home. She also noted that there had still been no referral for counseling, and that she had been unable to schedule an appointment with McGaughey’s supervisor.

“I am appalled and devastated! This is really outrageous and unacceptable in every way! I truly cannot believe how cruel you people are, really it blows my mind!” she concluded.

Part of an email Theresa sent to caseworker Jacelyn McGaughey after an upsetting visit with her daughters.

Theresa decided she was going to file a grievance with the agency for how her case was being handled. But to do that, she needed to meet with McGaughey’s supervisor, Stephanie McDaniel. This proved difficult.

“Almost every time I’ve left the agency, I’ve said, ‘I need to set up a meeting with Jacelyn’s supervisor,’ and they just look around at each other. Like, nobody will schedule anything for me,” Theresa said at the time.

“I asked for the grievance form and she, Jacelyn, in one of the emails, sends me the list of things I have to do to file a grievance on them. The first is meet with the caseworker. The second is meet in your home with the caseworker. The third is meet with the supervisor and the caseworker. They won’t let me get to step three. They won’t let me meet with the supervisor.”

Justin Johns, Rylenn and Everly’s father, had a visit with his daughters not long after. He also noticed the bruises, but the girls weren’t comfortable discussing the foster home in front of the visit supervisor, so he took them outside. There, Rylenn told him the same thing she’d told Theresa. She was scared. The family was mean. She didn’t want to go back.

Justin reported this to Children Services. They told him they hadn’t yet received any reports about the foster home, but that they would look into things.

Stressors

Removing a child from the home is inherently traumatic.

Everyone who works in and around the system acknowledges this.

Kids are bonded with their parents in a way that has enormous psychological importance. Rupture that bond, and the consequences can be devastating.

“That is the big lie of American child welfare: It equates child removal with child safety,” said Richard Wexler, executive director of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform. “The problem with this system is not that it hurts parents, though of course it does. The problem is that it hurts children. It hurts children by inflicting the enormous inherent emotional trauma of being torn from everyone they know and love.

“That trauma — the motivation may be different — but that trauma is the same in Athens, Ohio, as it is on the Mexican border. So if you remember the cries of the children taken there, it’s the same.”

It’s not just the time apart that’s traumatic. Multiple experts have said that the act of removal itself is enormously harmful.

“Everything we know about the research of family separation tells us it’s the initial process to separate a child from a parent that we really need to take a look at,” said University of Michigan law professor and juvenile court expert Vivek Sankaran. “Once that’s done, the damage is pretty irreparable.”

Theresa sent caseworker Jacelyn McGaughey this text two days after her children were removed. She would ask repeatedly for counseling in the weeks and months to come.

This is not to say it’s never necessary to separate children from their parents. But it reflects the immense toll that removal takes on children, even when they may have suffered genuine abuse at home.

It further raises the stakes for caseworkers deciding whether to pursue removal. In cases where the removal is unwarranted, children suffer lasting harm for no reason.

Agencies know all this and are trying to do something about it. Athens County Children Services has itself pioneered an outreach program designed specifically to connect families in need with helpful resources through caseworkers placed in local schools — thereby heading off any discussion of removal from the outset.

Throughout Ohio, children services agencies also employ “alternative response” in situations where caseworkers don’t feel removal is necessary.

In alternative response, “We don’t go in and identify a perpetrator and a victim,” explained Scott Britton, assistant director of the Public Children Services Association of Ohio. “We identify what services might be needed in the home to stabilize that family, because we recognize early on that removal into foster care is not going to solve this problem.”

Still, alternative response only represents about 40% of child welfare cases statewide, according to data compiled by Britton’s organization. The numbers for traditional response tend to be slightly higher (there are other categories not involving abuse or neglect that bring the total to 100%).

That’s a lot of removals producing a lot of traumatized kids.

There’s another, related problem: What kids experience in foster care can be just as bad, or worse, as what they left behind.

One trauma after another

Rylenn and Everly’s experience in foster care is not uncommon, according to critics of the system.

“We have seen it a lot that foster parents, and the agency itself, get away with things they wouldn’t tolerate from our clients,” said Cuyahoga County public defender Denise Ferguson, who represents parents in child removal cases.

Ferguson pointed to a report by the Cleveland Plain Dealer last summer of rampant abuse and neglect in a facility operated by Cuyahoga County Children and Family Services as an example. The agency housed children at the facility because they couldn’t find placements for them. There, the children experienced horrific abuse and neglect — exactly what they were in the system to escape.

Ferguson recalled a case she handled in which a well-respected foster father — “foster father of the year,” as she described him — was found to have raped the boys in his care. When one of the boys returned home, he inflicted those same behaviors on his siblings. His mother lost custody again due to the boy’s behavior.

“Where’s the logic?” Ferguson asked.

The irony is not lost on critics. Not only is removal itself traumatic; in many instances, what comes next causes even more trauma.

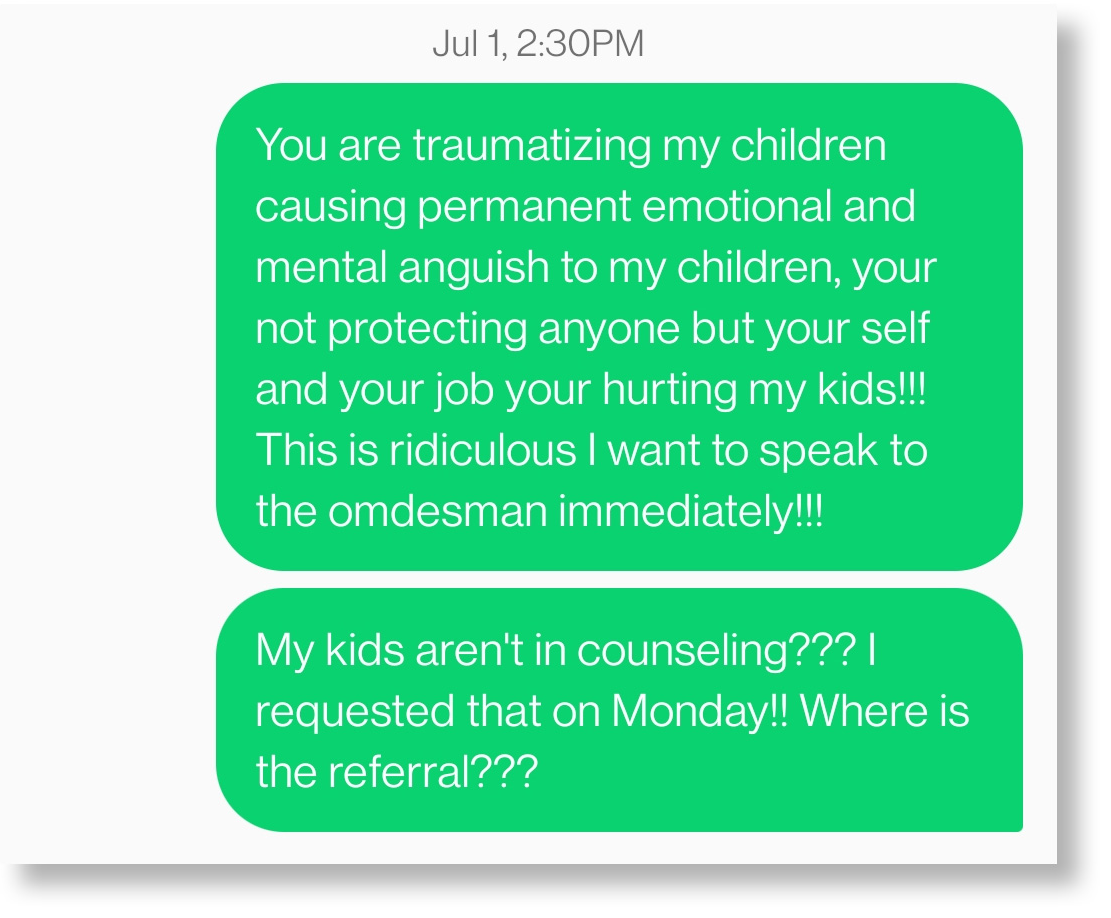

Theresa texted caseworker Jacelyn McGaughey to express her dissatisfaction.

“One independent study after another finds abuse in one-quarter to one-third of family foster homes, and an even worse rate in group homes and institutions,” said reform advocate Richard Wexler.

He said those numbers are significantly worse than what gets reported in official records because, in the latter case, agencies are essentially investigating themselves.

“There is a huge incentive to see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil, and write no evil in the case file,” Wexler said.

Athens County Children Services spokesperson Matt Starkey said his agency vets potential foster homes thoroughly.

“We do home studies, and those are very extensive, where our foster recruiter will go into the home,” he said. “We’ll interview parents. We’ll interview children in the home if there are other children. We’ll do a background check on the parents.” The process takes a year to complete.

However, Starkey also acknowledged there aren’t enough foster homes in Athens County to meet the need. That’s why some kids go to other counties.

The lack of beds for kids puts additional strain on a system that already struggles to find quality foster homes.

“We need more foster parents,” said Scott Britton of the Public Children Services Association of Ohio. “We need foster parents who are willing to work with older children with behavioral health challenges, so that we don’t have to place those children in congregate care or residential facilities, which we know they don’t get good outcomes from.”

Conversely, Wexler said the only solution to foster care is to have less of it. He argued the current crunch is a byproduct of agencies’ overzealous interventions, and that with better support services, fewer removals would be needed. That includes offering parents better legal representation to push back against unnecessary removals.

“Politically, it’s portrayed as, ‘Oh, you’re going to provide great defense for child abusers,’” Wexler said. “No, you’re going to actually be providing help for their children so they don’t endure the misery of foster care and the risk of abuse in foster care.”

A new placement

After seeing the bruises, Theresa no longer believed Children Services would do anything to help her daughters. So, she went to the Athens County Sheriff’s Office to file a report on the foster home.

The deputy she spoke with said he couldn’t help her. Her daughters were assigned to a foster home in Muskingum County, not Athens. She’d have to reach out to the Muskingum County Sheriff’s Office instead.

She did.

On July 19, Muskingum deputy Adam McGee filed a report about his visit to the foster home where Rylenn and Everly were staying.

He wrote that he interviewed the foster mother on her porch. Glancing through the front door, he “was able to see into the residence which appeared to be maintained and not of poor living conditions.”

The foster mother consented to the deputy interviewing the girls alone. McGee wrote that initially, Rylenn told him everything was fine.

Then he noticed the bruises on Everly’s legs. Everly wouldn’t speak, so McGee asked Rylenn where the bruises were from. Rylenn acknowledged that the foster parents’ son had pushed Everly off the slide.

McGee contacted Theresa and informed her of what he’d seen. He then contacted Children Services supervisor Travis Boggs. McGee wrote that Boggs “informed me that he knew issues have been brought to their attention and are being looked into.”

The next day, Rylenn and Everly were moved about 30 miles to a new foster home in Heath, Ohio.

“Rylenn was excited,” Theresa recalled. “The first thing she says to me is, ‘Mom, what did you report?’ And I’m like, ‘I told you, Mommy’s doing everything that she can, Rylenn.’”

“It’s not that I wasn’t doing anything,” Theresa said. “It’s that nobody was listening to me and I had to do this myself.”

The only reference to the new foster home in the agency’s activity log for Theresa’s case is in communications from Cheryl Boger, Theresa’s mother.

“Cheryl reported the girls are in a new foster home with an older lady,” reads one of the notes in the activity log.

Theresa claimed that McGaughey moved the girls without telling her supervisor, suggesting some kind of breakdown in communication. That claim could not be independently verified.

Kinship

The new foster home proved far more hospitable. The woman there seemed excited to have Rylenn and Everly with her. She bought them snacks and nail polish. They watched movies together.

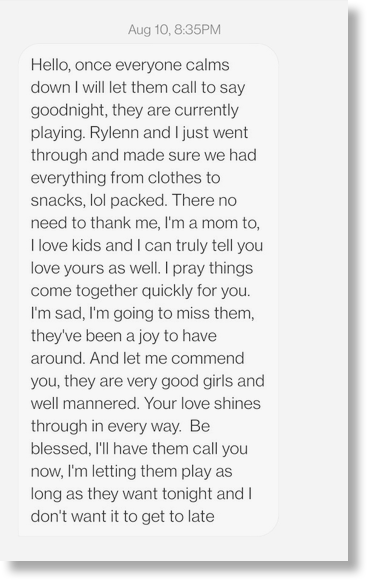

A text message from Rylenn and Everly’s new foster mother in Heath, Ohio.

Meanwhile, Athens and Butler County children services were working together to arrange a kinship placement with the girls’ grandmother, Cheryl Boger.

Legally, agencies are required to make intensive efforts to place children with relatives and to document those efforts with the court. But the process for placing the girls with Cheryl, which began directly after the removal, was taking a long time.

The reason is unclear. McGaughey explicitly mentioned Cheryl as a potential kinship placement for the girls at the shelter care hearing on June 27. Despite that, the girls went straight to a foster home after the hearing.

Cheryl — who contacted the agency several times to express her concerns about the case — was told she had to wait for Butler County Children Services to conduct a home study and run background checks on her and her partner before she could take Rylenn and Everly.

Those home assessments are required for prospective kinship placements. However, children can be placed with kin on an emergency basis while those assessments are being conducted. In fact, this is exactly what happened with Theresa’s boys, who were sent immediately to the house of their aunt, Jaime Boger.

So why didn’t the girls go to their grandmother?

The caseworker activity log offers few answers, though it does seem the agency had doubts about Cheryl. She had a leg wound that impeded her mobility, and there was confusion about her living situation. An entry in the activity log also claims that Cheryl had mistakenly said she lived with Jaime, when in fact she lived with another of her daughters, Christina.

After that exchange, a caseworker — either McGaughey or her colleague Stephanie Blaine — wrote in the activity log: “This worker feels that Cheryl was being misleading thinking the girls would come to her sooner.”

There are signs this was part of a larger problem, as well. Although state law mandates that agencies make intensive efforts to place children with relatives, the Public Children Services Association of Ohio report from 2021, the latest one available, shows that only 26% of children statewide were placed with kin. By contrast, 55% were placed in foster care.

Whatever the reason, Cheryl had to wait for Butler County Children Services to complete its home study before she could take the girls. Unfortunately, the Butler employee responsible for home studies was on vacation for part of July. It took until July 26 for the agency to finally approve Cheryl as a kinship placement and another two weeks for the girls to move in with her.

In total, Rylenn and Everly spent six weeks in the foster system.

Rylenn and Everly in a photo taken a few weeks after they were placed with their grandmother. [Photo courtesy of Theresa Fogel]

Theresa was relieved when the girls finally moved in with their grandmother. But the maltreatment they had suffered at their first foster home infuriated her.

“I talk to them about four or five times a day, which is nice, because it’s all on video and I get to see my kids all the time, you know?” Theresa said shortly after her girls arrived at Cheryl’s. “And Rylenn, her and I have talked about that place. I mean, my daughter’s traumatized from being in that house. That foster home. She is traumatized.”

Cheryl made similar observations. “The oldest one, which is 10, she cries a lot. All she wants is her mom,” she said at the time.

“The little one, she’s sore. She’s got quite the temper and she’s angry on the inside. She holds a lot of anger and she don’t know how to express it.”

McGaughey assured Theresa that referrals for counseling were being made, but the counseling never materialized.

Meanwhile, Theresa was also struggling with her housing situation. After a failed negotiation, her landlord had finally made good on his threat to evict her. It was within Children Services’ mandate to help her find new housing, but the agency had not done so. And Theresa couldn’t imagine that being homeless would do much to help her case.

“A quality assurance issue”

By the end of July, Children Services had missed the statutory deadline — 30 days after removal — to file a case plan. The document was supposed to explain what Theresa had to do to get her kids back.

This was a significant oversight.

According to Matt Starkey of Athens County Children Services, the case plan is a central component of a child welfare case from the moment the shelter care hearing ends. It is a step-by-step guide describing what each member of the family has to do to make reunification happen. They are developed in conjunction with the parents and form the backbone of every court hearing.

But as of Aug. 1, Theresa had not heard anything about a case plan from McGaughey. She had, in fact, only met with her caseworker once. She had no idea what the agency even wanted her to do to get her kids back.

Theresa reached out to the state of Ohio’s newly formed Youth and Family Ombudsmen Office, which provides a venue for parents to file complaints about children services agencies. She was told her case would be handled by a woman named Christine Pater. Pater summarized Theresa’s complaints in an email to her following their initial meeting:

- You were told that you refused to agree to a Safety Plan but you stated that you were never offered a Safety Plan.

- You still do not have a case plan. Will you be invited to a meeting to have input on your case plan?

- You want to assure that your children will be receiving counseling from Access Counseling.

- You would like the medical records for when your children were in foster care and want to know what vaccines or immunizations they received without your consent.

- You want to know the results of the referral you reported to Muskingum County regarding your children while they were in foster care.

- What if anything has been resolved regarding your visitation and having to drive three hours each way to visit?

Pater also explained to Theresa how to file a grievance through Children Services itself. Unfortunately, that process was delayed because the agency sent the disposition letter summarizing the charges against her to her former address in Butler County by mistake.

McGaughey apologized for that in an email and explained they had been unable to change Theresa’s address in their system. Theresa was not impressed by the excuse.

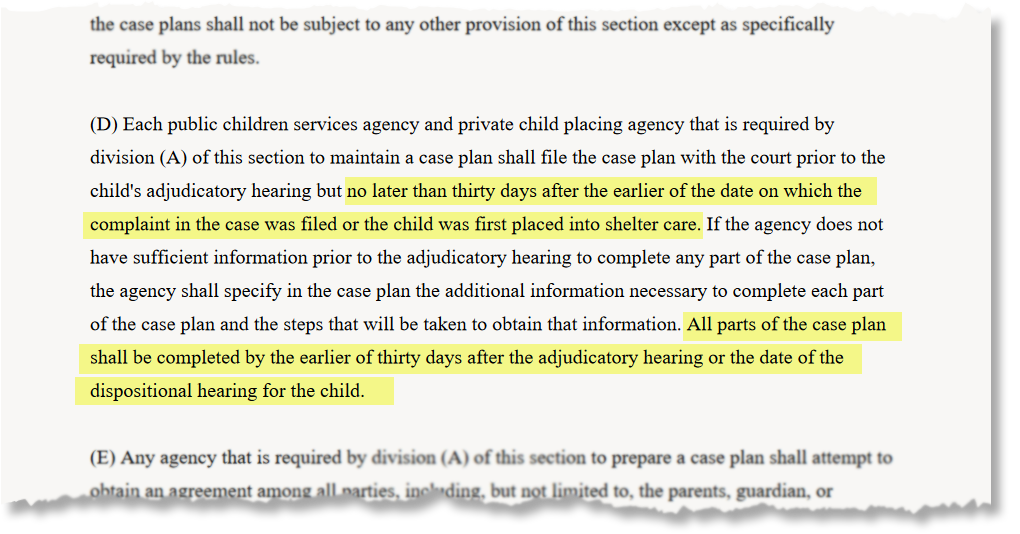

Theresa later tracked down the Ohio Revised Code section that spells out the timeframe for agencies to submit a case plan. Included in the law is this sentence: “Each public children services agency (...) shall file the case plan with the court prior to the child’s adjudicatory hearing but no later than thirty days after (...) the child was first placed into shelter care.” (Emphasis WOUB’s.)

Theresa sent that section of the revised code to Pater, who affirmed that was the rule governing case plans.

“So how is this legal?” Theresa wrote back.

Pater replied that if the agency missed the 30-day deadline, it was a “quality assurance issue meaning they did not follow policy/rule.”

Section D of Ohio Revised Code 2151.412 lays out the timeline for agencies to complete a case plan.

Theresa had worked out as much already. When she finally received her disposition letter, she followed Pater’s advice and filed a formal complaint with Children Services.

In her mind, her children had been taken for no reason. No one was doing anything they were supposed to. Now her daughters had suffered abuse in foster care.

The adjudication — her moment of truth — was close at hand. She was ready to stand up for herself.