The Athens County juvenile courtroom, where Theresa Fogel’s hearings took place. [Max Correa | WOUB]

Chapter 5

The deal

On Sept. 2 — two months and one week after Athens County Children Services took her children — Theresa Fogel was ready to get justice.

It was the day of her adjudication hearing: The day the agency would finally have to show its hand and prove her children were abused or neglected.

Theresa knew that hand was empty. She’d seen the discovery from the assistant prosecutor. There was no evidence in it to support even the weakest of the allegations against her.

Theresa also was certain that Children Services had broken the law.

The agency was supposed to file a case plan 30 days after her children were removed. That plan was meant to describe the family’s situation and identify what needed to happen for her to get her kids back.

It had taken almost twice that long for the agency to send out Theresa’s case plan — which, contrary to state policy and statute, had been designed without her input.

She arrived early to the courthouse with her boyfriend, Tyler Tingley, her friend and neighbor Mimi Shuttleworth and Becky Fulks, an advocate from a local domestic violence shelter. They chatted in the lobby as Children Services personnel filtered in and out of the juvenile courtroom.

The father of Theresa’s daughters, Justin Johns, was also in the courthouse that day. He stood away from everyone else in the hallway with his mother and attorney.

The hearing was scheduled for 10:30. At 10:20, Theresa’s attorney, Jon Getson, still had not appeared. Theresa kept checking the time.

At 10:30, Getson was still not there. The hearing was due to start. This was her moment to fight back, and her lawyer was missing.

He arrived at 10:31. With a wave, he walked past Theresa and into the courtroom.

He emerged some minutes later and pulled Theresa aside. The state had an offer. He whispered the details to her.

When Theresa rejoined the group, there were tears in her eyes. The agency was going to return her girls. Not only that, but it would drop the abuse and neglect charges against her.

There was just one condition: She had to agree to something called a “dependency.” Do that, and Rylenn and Everly would be home a week after Rylenn’s 10th birthday.

How could she say no?

Clear and convincing evidence

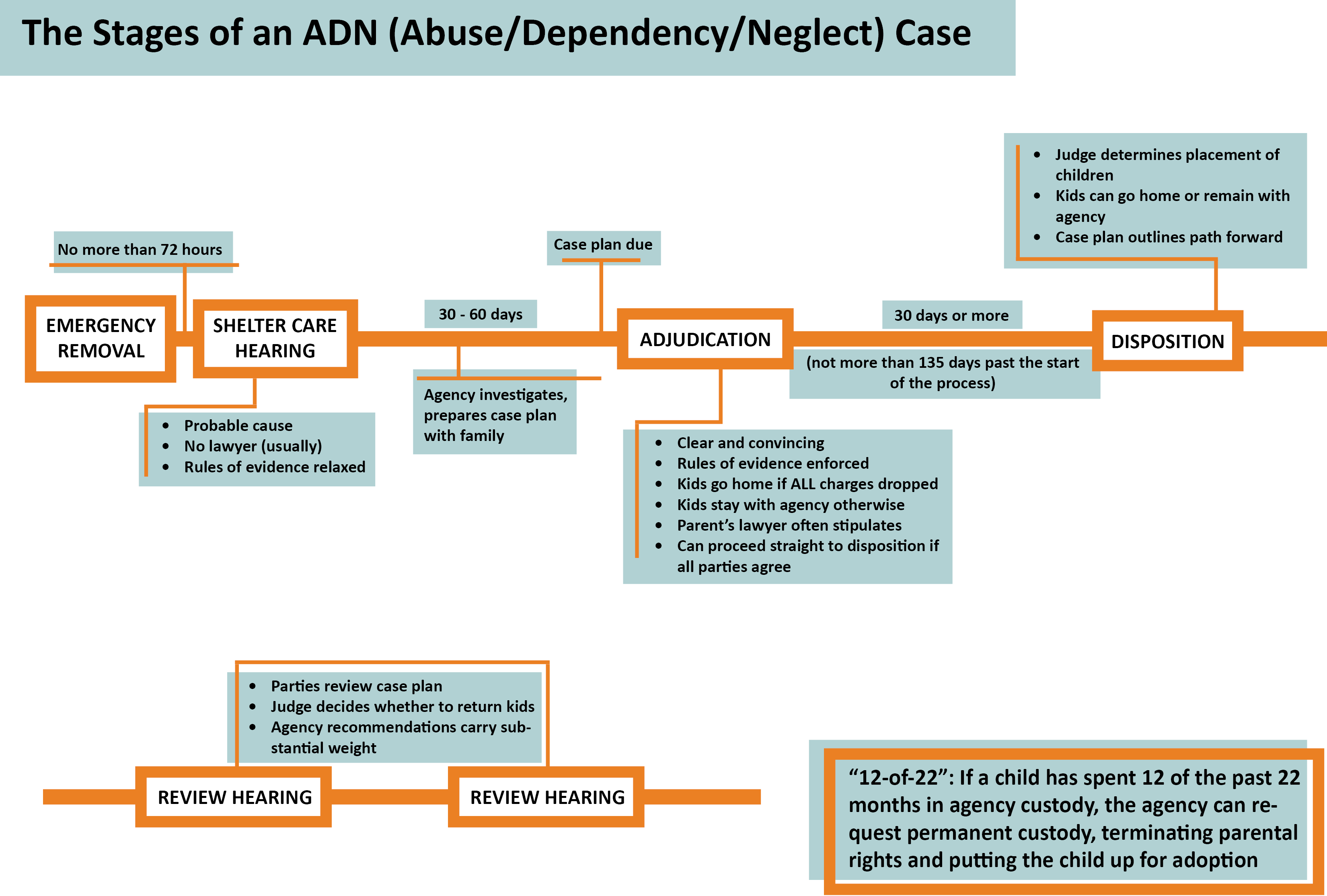

In theory, adjudication is the trial part of a child removal.

At an adjudication, parents choose whether to challenge the accusations against them or agree to a deal (also known as stipulating). If they challenge, then the state — that is, the children services agency — has to prove the children it removed were abused, neglected or dependent at the time of removal.

The trial is held before a judge; there’s no jury. Both sides call witnesses, present evidence and attempt to convince the judge to find in their favor.

The agency has the burden of proof, and the bar is higher than it was at the shelter care hearing. Now, the standard is clear and convincing: Lower than beyond a reasonable doubt, but significantly higher than probable cause. The rules of evidence are enforced and hearsay is inadmissible.

In other words, it would no longer be enough for Jacelyn McGaughey, the Children Services caseworker who removed Theresa’s children under an emergency court order, to simply recite the allegations made by Theresa’s two sons to the court. The state would need to show hard evidence to back up those claims.

The juvenile court judge makes the final decision at an adjudication. If the judge finds in favor of the parents on all counts, the case is closed and the children are returned. However, if the judge finds even one of the complaints to be valid, or if the parties make a deal and there is no trial, the case remains open.

When that happens, a third hearing, the disposition, is scheduled for the following month. Meanwhile, the children remain with the agency.

This is where the problems begin for parents and the attorneys who represent them.

Even if the most serious allegations are dropped or disproved — even if the “imminent threat of serious harm,” the legal justification for the emergency removal of the children, disintegrates — the agency often keeps the kids after an adjudication.

That’s because it usually wins on at least one count: dependency.

It can mean anything

The Ohio Revised Code defines a dependent child as one “whose condition or environment is such as to warrant the state, in the interests of the child, in assuming the child’s guardianship.”

In other words, a child is dependent when an agency believes it is and a judge agrees. It’s the “no fault” provision: The parent isn’t capable of caring for the child, but not because of any malintent.

Ohio Revised Code 2151.04 defines a dependent child. Section C in particular leaves ample room for interpretation.

“I mean, how broad can you be?” said Erie County public defender Kelli Jelinger.

That definition is extremely subjective.

Agencies do have guidelines to help shape their decisions around dependency, but at the level of individual cases, few people outside the agency are checking to make sure those guidelines are followed.

Because an agency’s internal deliberations are confidential by law, it’s hard for members of the public to assess how rigorously caseworkers and their supervisors follow protocol.

There are, in theory, dependency situations in which a child’s safety is at serious risk. But critics say it’s within an agency’s power to simply make a negative observation about a household, label it a dependency, and win the adjudication.

“Dependency is, if I feel like it, I’ll take the child,” said Richard Wexler, executive director of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform. “State law basically gives them carte blanche.”

Cuyahoga County public defender Denise Ferguson offered more measured criticism. “They have to show that whatever the dependency is negatively affects the child,” she said. But that doesn’t stop agencies from alleging dependencies she finds shallow.

“Dad has been accused in criminal court of getting in a bar fight or something. Therefore, dad’s violent. We don’t know if he’s gonna take it out on the kids. Not that he ever has in the past. But I’ve seen those types of arguments made,” she said.

Wexler said it’s also extremely easy for caseworkers to conflate dependency with poverty. They are not supposed to be the same, but the distinction is blurred at best.

Plenty of things a caseworker may find disturbing about a household — say, a lack of food — could result from economic hardship, not any fundamental incompetence on the part of the parent.

Wexler argued these ambiguities make it easier for agencies to disproportionately target poor and nonwhite families.

National data show conclusively this is an issue in child welfare. And in Ohio, more removals are carried out for dependencies than abuse or neglect.

It may not be surprising. Jelinger described one case in which a man briefly lost custody of his child because a vendor at a baseball game accidentally gave the boy a Mike’s Hard Lemonade, which contains alcohol.

“Even an accident could result in a dependency claim if JFS (Job and Family Services) so wanted it to happen,” Jelinger said. “And that is a very scary situation.”

The father in that case was a prominent local figure and the child was returned after a few days.

Many parents aren’t so lucky.

Even if the most disturbing allegations are false, one dependency allegation, no matter how minor, is enough for children services to carry the case forward from an adjudication.

“You can almost always justify a dependency finding,” Jelinger said. “Almost always. Because it’s so general. If there’s testimony, you can almost always find it.”

Jelinger has many years of experience representing families. She has helped parents get their kids back, but has never once won outright at an adjudication. It’s just too easy for the agency to prove a dependency.

This can easily cause a case to drag on by at least another month.

Say an agency suspects a child is being physically abused and faces unstable housing. It removes the child, because the alleged physical abuse constitutes an imminent threat of serious harm. Then it turns out that the agency was wrong: There was no physical abuse. But the housing instability, which the agency flagged as a dependency, was real.

The judge may not have signed off on the initial removal if the complaint were just about unstable living conditions, because that alone is unlikely to be an imminent threat of serious harm. But it may be all the agency needs to show to win the adjudication. And that means the agency will likely keep the kids due to the housing insecurity, even though it took the kids to prevent abuse that wasn’t really happening.

“Sometimes the system isn’t fair. I mean, there’s no other way around it,” public defender Denise Ferguson said.

It is important to note in the above scenario, the judge may decide to return the children to the parents at the third hearing, the disposition. That’s still another month in foster care. And it’s not a foregone conclusion the kids will come home.

Parents can appeal their adjudications, but the process takes six months or more. The agency retains custody during that time. That’s hard for many parents to stomach.

Appeals can only do so much when adjudications are hard to win. Sometimes, it’s more straightforward to just cooperate with the agency and hope the judge decides to give the kids back.

Because dependency sounds much less serious than abuse or neglect, it also gives agencies a powerful bargaining chip.

“My prosecutor, and most that I work with here in this part of the state, will say, ‘You know what, you’re right,’” said Jelinger. “‘I filed it as an abuse case, but if you admit to a dependency only, I will withdraw the abuse and neglect allegation.’ All my clients hear is, they’re not charging with abuse and neglect. That’s all they hear. And I’m like, it doesn’t really matter.”

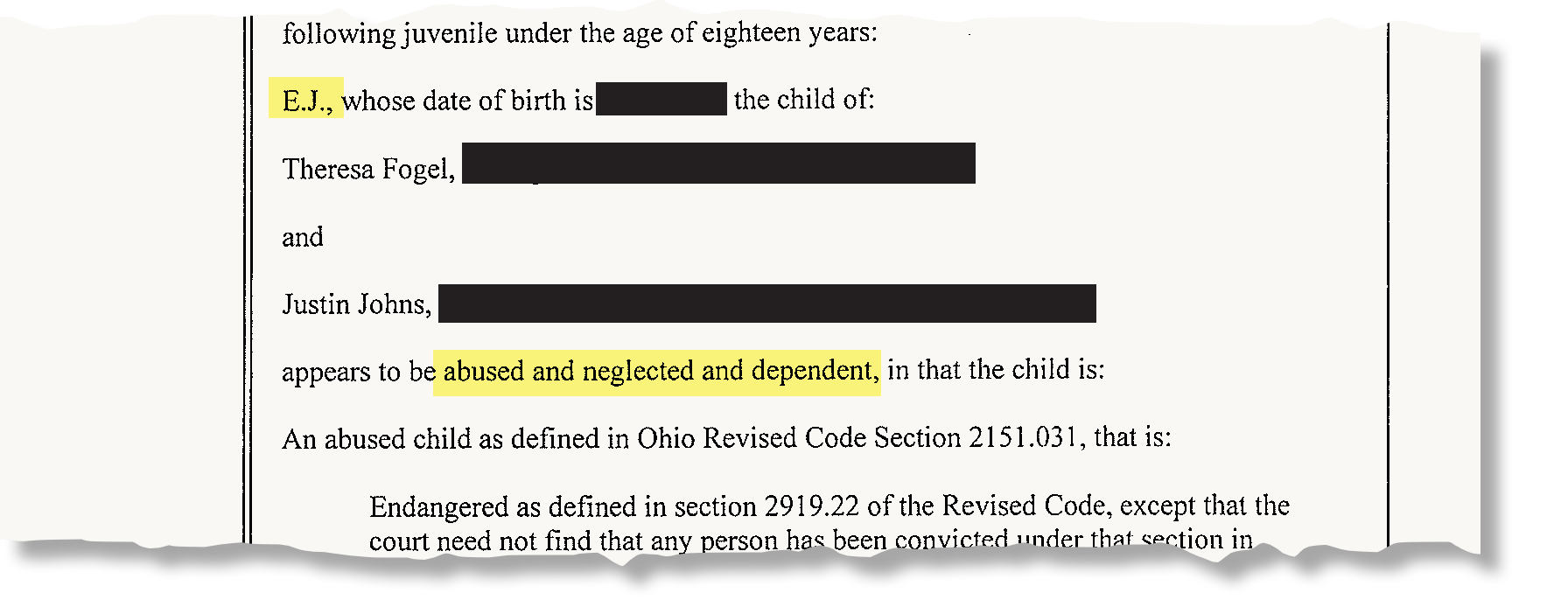

Children Services alleged that Theresa’s children were abused, neglected and dependent. The agency later offered to drop the abuse and neglect allegations at the adjudication if Theresa just stipulated to a dependency.

Whether parents agree to a finding of abuse, neglect or dependency, there is no difference in what happens to their children. They have forfeited their right to a trial and the agency retains custody until the disposition hearing — and often much longer.

“It really doesn’t matter whether the allegations … are true, because the agency may never have to prove them, because the agency will negotiate with the parents’ attorney and try to get a stipulation. And if you stipulate, the agency is proving by clear and convincing evidence that they have a right to be involved,” Ferguson said.

It’s possible Theresa could have won at her adjudication if she had challenged the agency’s allegations. The case against her was extremely weak, even with regard to the dependencies. There was ample evidence that her house was stocked with food and the family was never homeless. According to Theresa, her drug tests were negative.

On the other hand, she was at risk of eviction in late June. She did briefly let Tyler drive on the way back from Butler County on June 25, even though he didn’t have a license.

Either may have been enough to keep the case open if the agency considered these dependencies and the judge agreed.

In the end, the question turned out to be moot. That’s due in large part to Theresa’s lawyer.

Appointed counsel

People who can’t afford their own legal representation get one of two kinds of lawyers: public defenders like Kelli Jelinger and Denise Ferguson, or court-appointed counsel like Jon Getson.

Public defenders have an office in the courthouse and receive a fixed salary. They are state employees.

Appointed counsel are attorneys in private practice who agree to take cases like these for an hourly rate. That rate is capped for each case.

Most Ohio counties rely exclusively on appointed counsel for abuse, neglect and dependency cases.

In Athens County, those lawyers are paid $100 an hour. The county then gets reimbursed by the state. The most it will reimburse for an abuse, neglect and dependency case is $1,500.

So, after 15 hours of work, court-appointed lawyers in Athens County stop earning money from a case like Theresa’s.

Athens County Juvenile Court Judge Zach Saunders said he wishes the rates for contract attorneys were higher, but it’s not his decision. The state sets the maximum reimbursement for different types of cases, and the county commissioners set the hourly rate.

He estimated that in 98% of the cases in his court, parents cannot afford an attorney and must rely on appointed counsel.

“A family in this situation will get about as much help from a cardboard cutout in a three-piece suit as they’re going to get from the court-appointed lawyer,” said child welfare reform advocate Richard Wexler.

Public defenders may not win many adjudications, either, but they still may increase the odds that parents will eventually be reunified with their children.

“We know that, and statistics show, that good legal representation can dramatically impact outcomes,” said Vivek Sankaran, a University of Michigan law professor and expert in the area of juvenile court.

Take Denise Ferguson. As a public defender, she’s salaried. Whether she spends two or 200 hours on a case, her pay remains the same. She does not lose money on long cases.

As early as the shelter care hearing, she looks for opportunities to get kids home. Maybe the agency didn’t consider alternatives to removal. Maybe a caseworker just misread the situation. If Ferguson finds out they cut corners, she’ll push back.

“Sometimes I just go to the prosecutor and say, ‘Seriously, we can either fight this out, or you can give 24 hours and go back out and look again,’” Ferguson said. That might be enough to get the agency to back down.

She estimated she wins about 10% of her adjudications. That may sound low, but considering just how difficult it is to actually clear a parent of a dependency charge, it’s not nothing.

“I actually got a child returned home halfway through adjudication because the magistrate was just so irate at the fact that the agency wasn’t protecting the child,” Ferguson said. “She’s like, ‘I have to decide at every hearing if there’s a reason for the child to remain out of the house. And I’m finding that there isn’t anymore, because you people are screwing this up more than mom ever did.’”

Much of that success depends on having a sympathetic judge or magistrate who won’t just “play it safe” by leaving children with the agency. Erie County public defender Kelli Jelinger said most judges defer to the caseworker.

“Generally, judges don’t want to upset the apple cart,” she said. “Judges have come to accept that unacceptable behavior is OK. They don’t understand why it’s so crucial that families not be separated, and, ‘Oh, poor Susie caseworker. She’s tried but she just couldn’t get it done but she’s not doing it maliciously.’ You know, that sort of argument.”

Jelinger doesn’t win adjudications, but she still handles these cases all the time. Even though she knows she probably won’t get the case dismissed outright, she actively works on compelling the agency to actually reunify the families.

If the agency did not make reasonable efforts to prevent a removal — which the law requires — she’ll file a motion to potentially cut the agency’s federal reimbursement for the foster care in that case.

She’s also threatened a caseworker with a contempt motion for not submitting a case plan on time.

Those actions may not change the outcome of an adjudication, but they can set up a strong appeal, speed up reunification and stave off many parents’ nightmare scenario: The revocation of parental rights and the permanent loss of their children.

Theresa’s lawyer, however, did what many court-appointed attorneys are compelled to do: move things along. Filing motions or fighting at the adjudication would chew up a lot of time. He largely did neither.

Things go as predicted

From the day Getson was appointed, Theresa wanted him to do one thing: Get her kids back quickly.

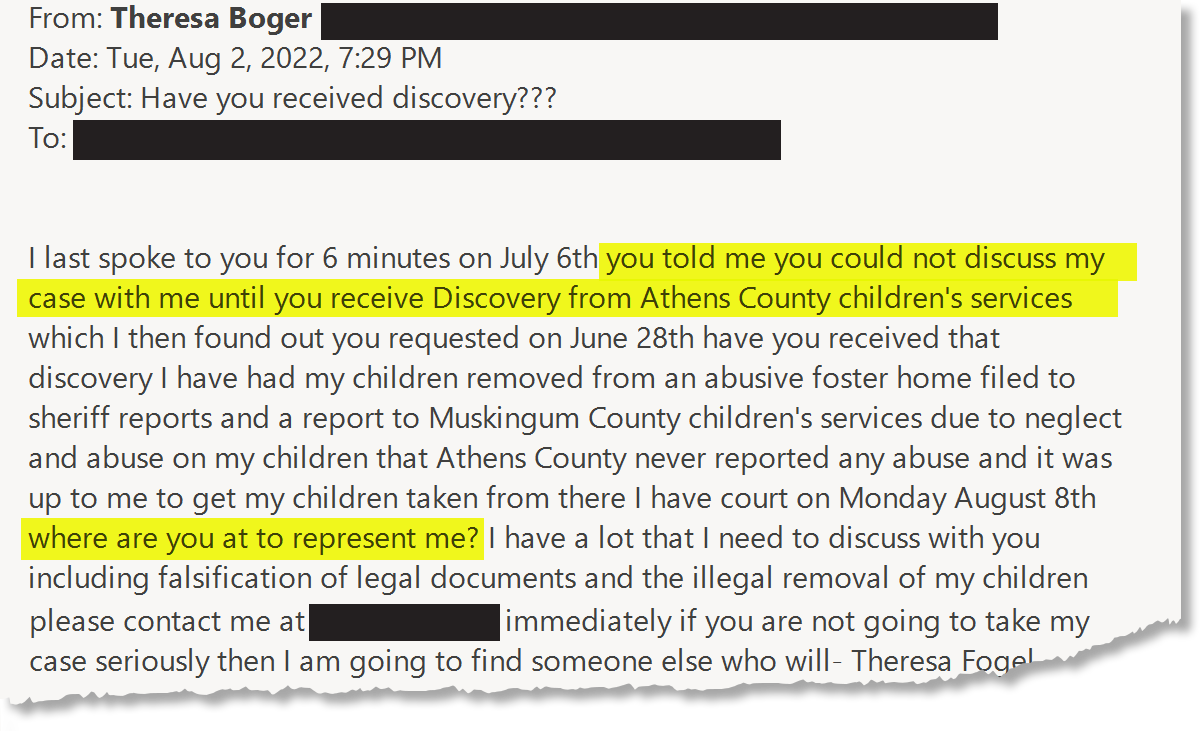

She emailed him regularly — by his count, as many as 10 times a day — asking to meet and venting her frustrations about the case.

Getson seldom responded. When he did, he told her he was waiting for Children Services to send him the discovery for her case. He felt there was no point in meeting before that.

One week before the date scheduled for her adjudication, Theresa was still emailing her attorney asking to meet.

(Jelinger and Ferguson both said they meet with their clients as soon as possible, regardless of discovery. They also said they would keep pressure on the prosecutor to deliver the discovery on time.)

Theresa took Getson’s unwillingness to respond as a sign he did not share her sense of urgency. As far as she was concerned, her children had been taken for no reason. She had ample documentation to prove it, if he would only meet with her face-to-face.

“I had left him already two voicemails that went unreturned, as well as then spoke to him for, literally, two minutes,” Theresa said at the time. “And he seemed very in a hurry and didn’t want to talk to me.”

Theresa’s adjudication was initially scheduled for Aug. 8. A couple of days before that, Getson did finally speak with her by phone for about 20 minutes. Theresa said the conversation was not especially productive.

“I was talking about, X, Y and Z has happened and I don’t understand why you’re not taking me seriously. I need an attorney that’s going to represent me and fight for me and my children,” she recalled saying. “I mean, I just went off on him.”

With the adjudication fast approaching, Getson still had not met with Theresa in person and still did not have the discovery.

It was hard to imagine what kind of fight he would put up at a trial not knowing what evidence the agency planned to present in support of its allegations. There was no way to prepare a defense.

But circumstances intervened. The court couldn’t find Blake Fogel, the father of Theresa’s sons, Josiah and Azriel. The hearing had to be continued.

At this point, according to Theresa, the prosecution acknowledged it must have overlooked Getson’s discovery request and agreed to finally send him the evidence the agency had collected.

Before leaving the courtroom, Theresa told Judge Saunders she was frustrated with Getson and wanted a new attorney. She said Saunders encouraged her to stick with him, so she did.

Saunders set the new adjudication for Sept. 2.

Theresa still wanted to go to trial. But Getson saw things differently.

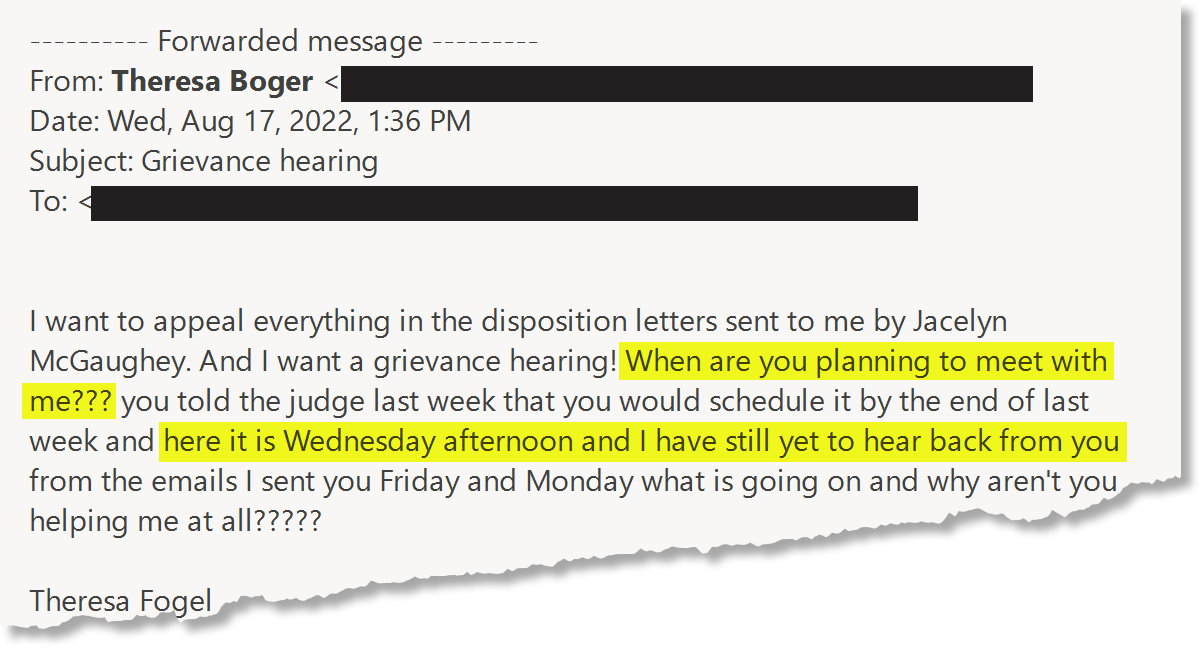

Theresa still struggled to meet with her attorney after the first scheduled adjudication date.

When Getson finally received the discovery, he decided there was enough in it for Children Services to prove a dependency.

He later declined to identify what that evidence was to WOUB, citing attorney-client privilege, but said he had little confidence in his client’s chances had he challenged the agency at the adjudication.

“In dependency cases, the bar that the State is burdened to meet is extremely low,” he wrote in an email to WOUB.

Theresa shared copies of the discovery she received from Getson with WOUB.

Very few of the documents pertain to the allegations against her, and those that do — namely the caseworker activity log — provide very little evidence in support of the allegations Children Services brought forward at the shelter care hearing.

“If I’ve gotten discovery and nothing is included in there, I would be telling my client, ‘Hey, I think we need to have a hearing. I think this does not show what is called reasonable efforts to prevent removal,’” public defender Jelinger said.

She said she would want to put people from the agency on the stand under oath and question them about the lack of evidence.

“Because one of a couple things could be happening,” she said. “Either they truly have not investigated, right? And it’s just not there. They’re hiding it, OK? Or they have failed to produce it to their own attorney, because of laziness or incompetence or whatnot. Or they failed to document it, OK? All of which are inappropriate on so many different levels.”

“The dark side of that is they say nothing and hope that the other side doesn’t fight it and then it just doesn’t get brought up,” she added. “And that is a problem.”

Getson didn’t see it that way.

“Two of the children had run away from home,” he wrote to WOUB. “At that point, they statutorily were dependent (and potentially delinquent) in the eyes of the Ohio code, and it was highly likely that most, if not all, of the children would have been found dependent.”

The runaway children Getson referred to were Theresa’s sons, Azriel and Josiah. Running away from home, in this case, meant going to the Glouster Public Library, where they made the allegations to a caseworker.

It is not uncommon for children in Glouster to go to the library for internet access, as Theresa’s boys did. Getson claimed there was more to it than that but declined to elaborate.

Running away from home was not listed in the original complaint, meaning Children Services could not use it as a dependency allegation at trial. Getson, however, believed he would lose if he tried to fight it.

That meant it was time to cut a deal. If Children Services had what it needed to win the adjudication, the best thing he could do for Theresa was encourage her to be as accommodating as possible. Any belligerence on their part would slow the process down.

Getson therefore also did not challenge the agency over its missing case plan, which by this point was long overdue.

“The case law states that the remedy for a case plan not being filed on time is for the agency to quickly resolve this by submitting a case plan. Challenging the lack of a case plan would likely only delay the proceedings,” he wrote to WOUB.

(Jelinger, conversely, has threatened a caseworker with a contempt motion over a late case plan. That’s considered a major escalation.)

Getson was more circumspect in his communications with Theresa at the time. He did not tell her that her chances of winning at the adjudication were low. Or if he did, this was not something Theresa ever understood.

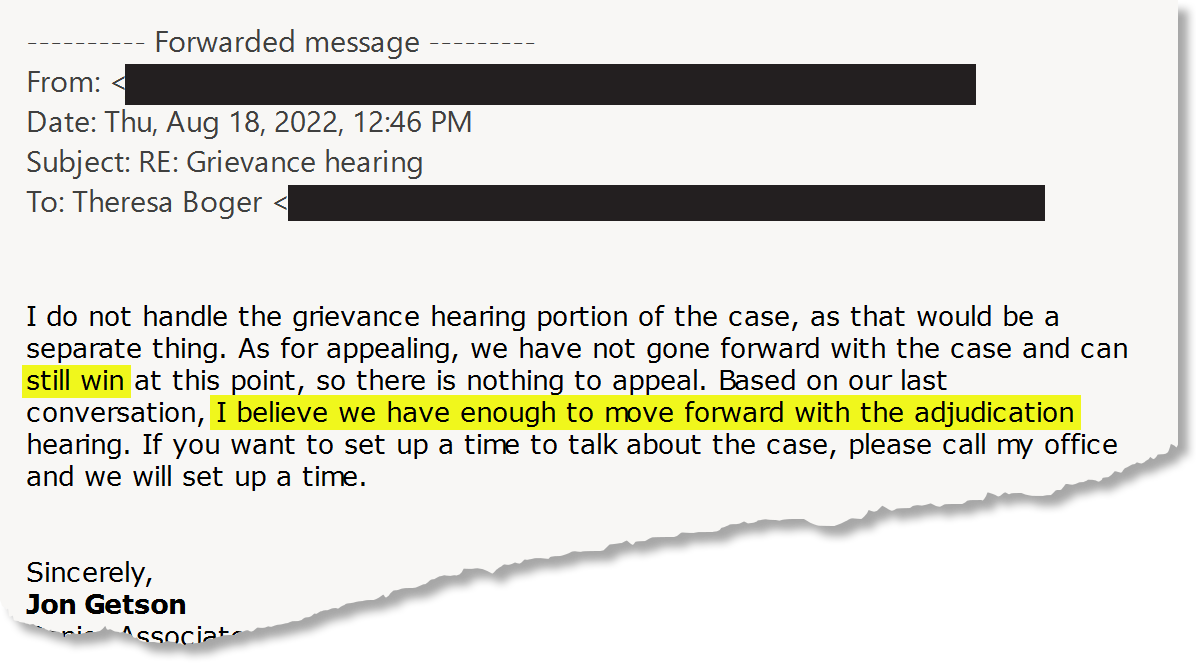

In an email dated Aug. 18, two weeks before the rescheduled adjudication, he wrote to her that they could “still win” and added: “Based on our last conversation, I believe we have enough to move forward with the adjudication hearing.”

Defense attorney Jon Getson’s email to Theresa on Aug. 18 indicating he believes she can “still win at this point.”

By that point, he still had not met with Theresa face-to-face, despite repeated requests from his client to do so.

On Aug. 22, Becky Fulks, the advocate from the domestic violence shelter, emailed Getson on Theresa’s behalf.

“She (Theresa) is desperately needing guidance and support from you regarding the custody of her children. She is feeling very isolated and uninformed on how to best proceed with court and could really use an opportunity to meet/speak with you,” Fulks wrote.

The email Becky Fulks sent to defense attorney Getson encouraging him to meet with Theresa.

Getson emailed Theresa shortly after receiving that message, but claimed his response was “in no way” connected to Fulks’ request.

He and Theresa met the following day. Theresa pleaded with him to fight for her.

“Again, I asked him, ‘You said you don’t have any children, correct?’ He said no. I said, ‘Okay, well, imagine that being your whole entire life, and that being ripped away from you for no reason. And you’re walking around every day wondering what you’ve done so wrong for your children to be gone for no reason.’ And I was like, ‘So you need to fight for me and my children,’” Theresa said.

Theresa next saw Getson on Sept. 2 at 10:31 a.m., one minute after her adjudication was set to start.

He strode past her and into the courtroom. When he came out, he immediately pulled an anxious Theresa aside.

What happened next played out exactly the way Jelinger and Ferguson said these things so often do: Getson told Theresa the agency would drop the abuse and neglect allegations if she agreed to a finding of dependency.

It’s not clear how exactly Getson explained the rest of the deal to her. What Theresa understood was that Rylenn and Everly would be home in a week. At that point, the legal particularities were not of primary concern to her.

Theresa took the deal. It wasn’t perfect. Presumably, Children Services could pull the girls out at any time. Azriel and Josiah would remain with their aunt in Butler County.

What Theresa wanted more than anything was to have her kids back. Now, at least Rylenn and Everly would be home again.

Judge Saunders would not have been privy to the negotiation. All he would have seen was what the attorneys told him: An agreement had been reached. Dependency was established.

Whether she realized it or not, Theresa had now agreed that the agency was justified in removing her children.

Saunders set a date for the disposition.

After adjudication

At the disposition, and at several subsequent review hearings, the judge decides what to actually do with the children.

The agency is largely in control of the process here. Now that it has won the adjudication, it can recommend when, if at all, the kids go home. Their testimony carries enormous weight.

Once parents lose their adjudication, they basically have to do whatever the agency says and hope it’s enough to get their children back.

Critics say there are many examples of parents completing their case plan as it’s written, only for the agency to renege and put the kids up for adoption.

“There’s no guarantee that even if you complete the case, your kids come home, because it’s based on best interest at that time,” Ferguson said.

According to Ohio Administrative Code Rule 5101:2-42-95, if a child has spent 12 of the past 22 months in agency custody, the agency can request a judge terminate parental rights. The reasons for termination do not need to stem from the original accusations against the parents.

Ferguson gave some examples of the rationale a children services agency might use to take kids from parents who did what was asked of them: “We don’t think you benefitted from any of the services on the case plan. You’re not bonded to your kids. Your kids don’t want to go home. They’re perfect. They’ve adjusted so well where they’re at. We think they should remain there.”

In these situations, the quality of the parents’ lawyer again makes a big difference.

Juvenile courts attempt to balance out the agency’s power in this area with court-appointed special advocates (CASAs) and guardians ad litem (GALs). In essence, CASAs and GALs are third parties in child welfare cases. They are meant to represent the interests of the child and work independently from the agency and the parents.

GALs are paid attorneys, whereas CASAs are trained volunteers. Their roles are otherwise similar. Athens County has a blended CASA/GAL program.

Judge Saunders said he relies heavily on his CASAs, whom he typically appoints after the adjudication (though he can appoint them earlier if he believes further investigation is warranted). CASA reports offer him an alternative perspective on a child’s needs. When the time comes to decide on that child’s future placement, he considers those accounts invaluable.

Because the reports go directly to the judge, they are not available to parents. Theresa was never able to acquire the CASA reports for her case.

Saunders said CASAs have, on some occasions, succeeded in changing outcomes as early as the shelter care hearing.

“There are times, especially if a parent does make statements, that sometimes CASA will speak up and we’re able to work something out where the child is returned home, or to a relative,” Saunders said.

Not everyone is so enthusiastic about CASAs.

To be a CASA, “basically, you have to be able to afford to give your time and then you get 30 hours of training and a little in-service,” said child welfare reform advocate Richard Wexler. “Who can be a CASA? Not a poor person working two jobs to make ends meet, clearly. They don’t have the time. The only people who can be CASAs are affluent people who can afford the time.”

This skews the demographics of CASAs toward white, middle-class women. Those volunteers, Wexler argued, then go on to pass judgment on low-income, often nonwhite, parents. There’s a potential for bias to creep in.

Wexler pointed to data on how CASA programs affect family outcomes as evidence.

“Study after study has found that CASA prolongs foster care, reduces chances of reunification, increases the chances of kids aging out,” he said.

Jane Novick, who used to direct the CASA program in Montgomery County, said CASAs are also limited in how effectively they can act as a check on the agency’s power.

“When some of my CASAs saw a problem with Children Services, it was next to impossible to do too much about it,” she said. Sometimes, her volunteers were ignored. Other times, the agency tried to get volunteers removed from the case when their findings ran counter to the agency’s interests.

Novick also said diversity training for CASAs was sorely lacking.

“We needed a much better training on cultural, racial, religious differences than the usual ‘Let’s all love each other,’” she said.

Saunders said he has high confidence in his court’s CASAs and their ability to deliver fair assessments to him.

“Athens is a very poverty-stricken area,” he said. “And these are volunteers that live in Athens County and that deal with it a lot on a daily basis in their normal jobs.”

The Athens CASA/GAL program declined to comment for the story.

The kicker

Justin Johns was also worried about his daughters.

Like Theresa, he’d seen the bruises from the foster home. He’d seen how scared Rylenn was and felt frustrated at how impenetrable Athens County Children Services could be.

So he decided to take things into his own hands.

As Getson and Children Services worked out their deal for Theresa, Justin and his lawyer discussed filing a motion for custody. Maybe the girls could come live with him.

It seems no one — not Getson, not Theresa, and not the agency — was aware of Justin’s intent. When his attorney announced during the hearing that Justin intended to file, it threw a wrench in everything.

All of a sudden, Children Services claimed it could no longer return Rylenn and Everly within the week. Now, the process would be lengthier. There would have to be a home study. The girls wouldn’t be back until after the disposition hearing, at the earliest.

Theresa was furious. She felt both the agency and her own attorney had lied to her. But there was nothing she could do. The ink had dried.

She’d stipulated to a dependency, and in so doing, forfeited her right to a trial. Children Services was off the hook. It would never have to prove any of the allegations against her.

Now, it would be up to the judge, with significant input from the caseworker, to determine if and when her children came home. Theresa could either play ball or risk losing them forever.

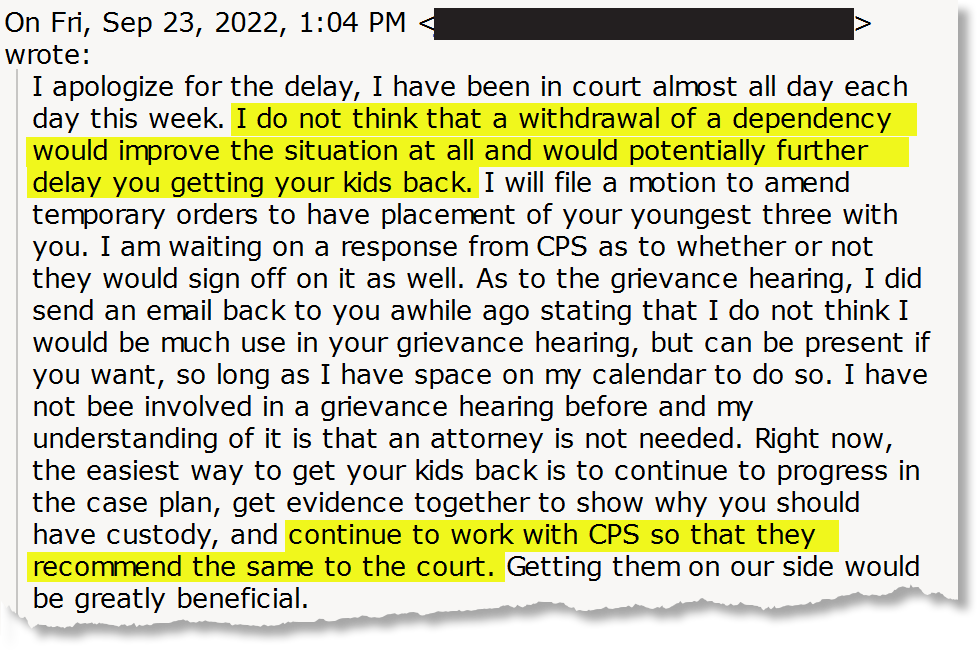

Theresa sent this email to her attorney on Sept. 22. She accused him of misleading her about what would happen if she stipulated to a dependency.

Children Services later informed Theresa the delay was actually because the court had never adopted a case plan for Theresa’s kids.

This explanation did not impress Theresa. Even if it was true, it was the agency’s fault the case plan hadn’t been filed on time.

“I want to withdraw my dependency plea,” Theresa wrote to Getson after the hearing. “I was lied to by you and by the caseworker you told me my children would be home in a week or two if I agreed to dependency.”

The next day, Becky Fulks, the advocate from the domestic violence shelter, sent a follow-up email to Getson, again asking him to meet with Theresa.

Fulks emailed Getson on Sept. 23 to express growing concern about the poor communication between him and Theresa.

Getson responded to Theresa about an hour after receiving Fulks’ message. “I do not think a withdrawal of the dependency plea would improve the situation at all and would potentially further delay you getting your kids back,” he wrote. He added that he would file a motion to amend temporary custody, but that he didn’t know if Children Services would sign off.

Getson’s email to Theresa on Sept. 23. He recommended that she do what parents in the system are expected to do: Follow the case plan, cooperate with the caseworker, and hope the agency recommends reunification.

Getson later wrote that the deal with Children Services never included anything about when Theresa’s daughters would come home. Theresa vehemently insisted it had.

The weekend after the adjudication was Rylenn’s 10th birthday. Theresa drove to Butler County to celebrate with her.

At that point, Rylenn and Everly were finally out of foster care and staying with their grandmother, Cheryl Boger.

“She had a great birthday,” Cheryl said. “Matter of fact, she will classify it as the best birthday ever.”

“The only thing the girl asked for was that she spend her birthday with her mom. That’s it. She asked for nothing else.”