Theresa Fogel and her son Azriel at his sister Rylenn’s birthday party in early September. [Photo courtesy of Theresa Fogel]

Chapter 6

Azriel

Content warning: This chapter includes mentions of suicidal ideation.

Theresa didn’t communicate with her 14-year-old son, Azriel, for most of July. She was told he didn’t want to speak with her. A week after the removal, he blocked her number.

Theresa had no doubt this was because of Josiah. In her view, Azriel just did whatever his older brother told him to.

In spite of that — in spite of everything they had done to her and to their sisters — she missed them both bitterly.

On July 28 at 2:04 a.m., Azriel finally reached out.

“Hey how’s it been,” he wrote. “I’m sorry for blocking you it was jus so overwhelming for me.”

A few hours later, Theresa replied, “I miss you! I’m mailing you a letter today. You should get it by Saturday. I love you Azzy.”

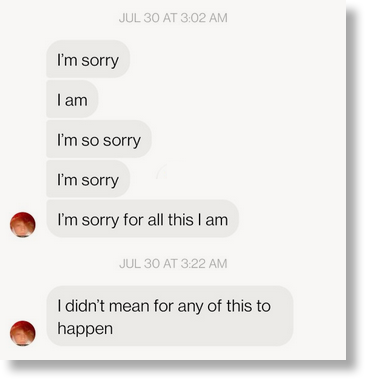

Over the course of the next few days, Azriel sent several apologetic messages. His sleep schedule appears to have been erratic. On July 30 at 3 a.m., he sent a string of texts saying “I’m sorry.”

“I didn’t mean for any of this to happen,” he concluded.

Azriel’s texts to Theresa in the early morning of July 30.

Shortly after 7 a.m., Theresa responded, “Azzy I love and miss you, I’m fighting to get you and the girls home. I’m doing everything I can please know that!”

Azriel told Theresa he was having panic attacks — eight in one day — and he cried himself to sleep. He also asked after their dog, Arlo.

He missed Arlo a lot.

However, he insisted he hadn’t been happy in Glouster. Theresa believed this was a new attitude. He’d been fine until shortly before the removal, when he went back to Butler County to see his girlfriend, Jayleigh. There, of course, he’d also been reunited with Josiah.

Then, on Aug. 1, Theresa got multiple disturbing updates. One was a call from Jacelyn McGaughey, her Athens County Children Services caseworker, telling her Azriel had attempted to run away from his aunt Jaime Boger’s house, where he and Josiah had been placed. The second was an email from Jayleigh.

“Hey this is Jayleigh Azriels girlfriend I am sorry to bother you right now but i am worried about azzy,” the email began. “azzy calls me every night crying because of the stuff he is going through.” It went on to say Azriel was not getting along with Jaime’s family.

Theresa also heard from a friend that Azriel had threatened to kill himself.

Whatever relief Theresa may have felt now that her daughters, Rylenn and Everly, were with their grandmother was quickly snuffed out. Her son was suicidal, and there was nothing she could do about it.

She had no doubts in her mind about who was responsible. Azriel had had issues before, but he hadn’t been suicidal. That happened after Athens County Children Services intervened.

Theresa had been demanding the agency arrange counseling for her children since the removal in late June. McGaughey had assured her arrangements were being made, but Theresa had her doubts. The news about Azriel made her even more suspicious.

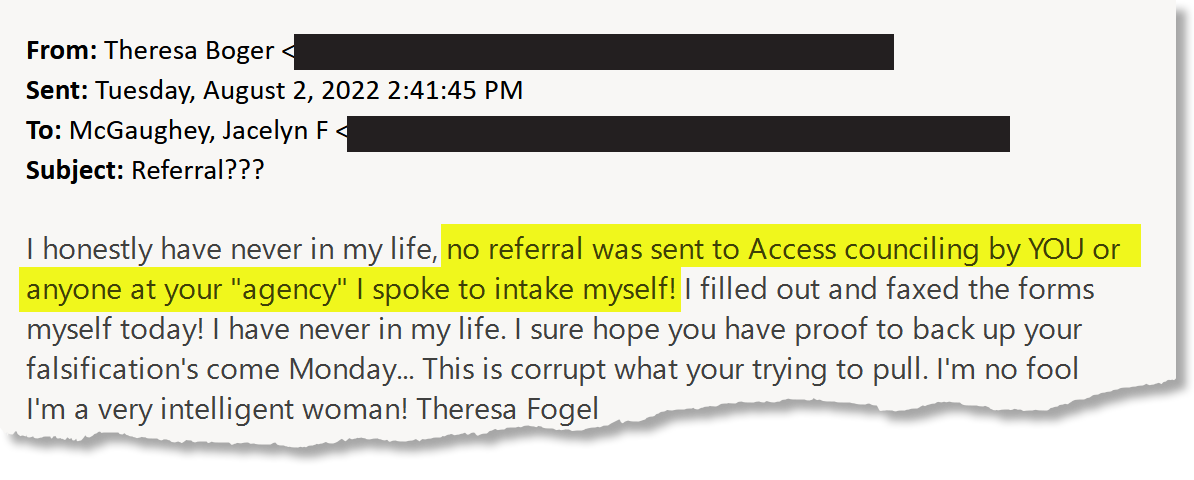

McGaughey had said she would send treatment referrals to Access Counseling Services, so Theresa called them. Access told her that they had not received any such referral.

Furious, Theresa sent an email to McGaughey.

“I honestly have never in my life, no referral was sent to Access counciling by YOU or anyone at your ‘agency’ I spoke to intake myself!” she wrote. “This is corrupt what you are trying to pull. I’m no fool I’m a very intelligent woman!”

Theresa’s email to caseworker Jacelyn McGaughey on Aug. 2 expressing her frustration over her children not getting into counseling.

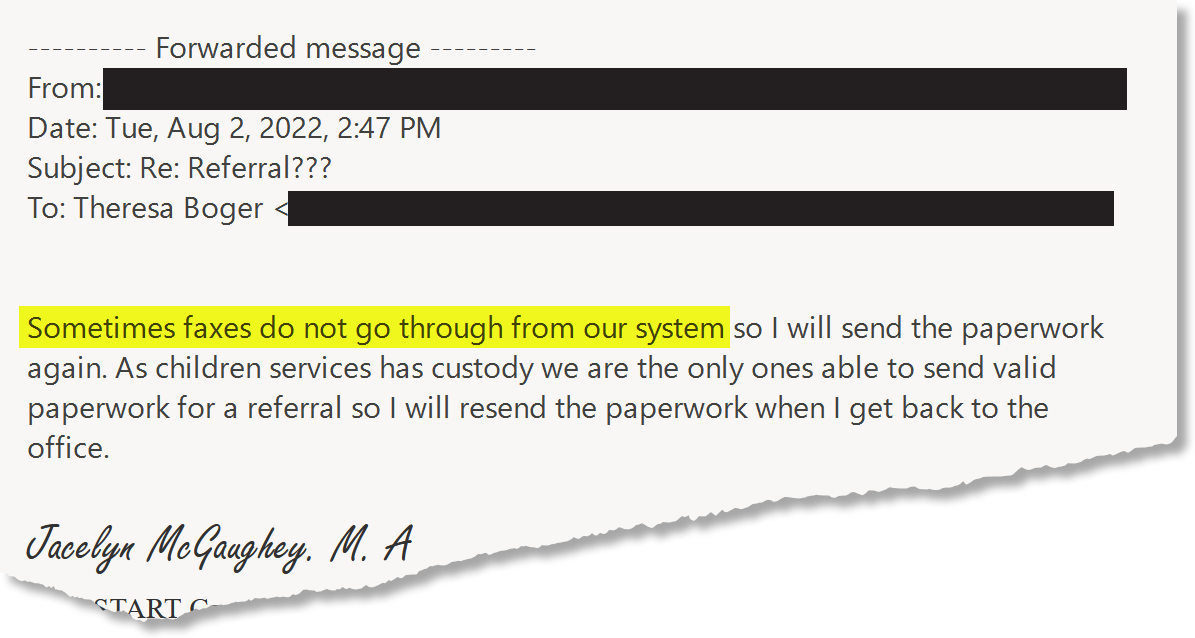

McGaughey replied, “Sometimes faxes do not go through from our system so I will send the paperwork again. As children services has custody we are the only ones able to send valid paperwork for a referral so I will resend the paperwork when I get back to the office.”

McGaughey’s response to Theresa on Aug. 2.

Two weeks passed and the counseling still did not materialize.

Theresa’s outrage grew. Her kids had been gone for months now. She hadn’t even seen Azriel since late June. Now her son was having thoughts of suicide. And — as far as Theresa was concerned — all because of false allegations Children Services couldn’t be bothered to investigate.

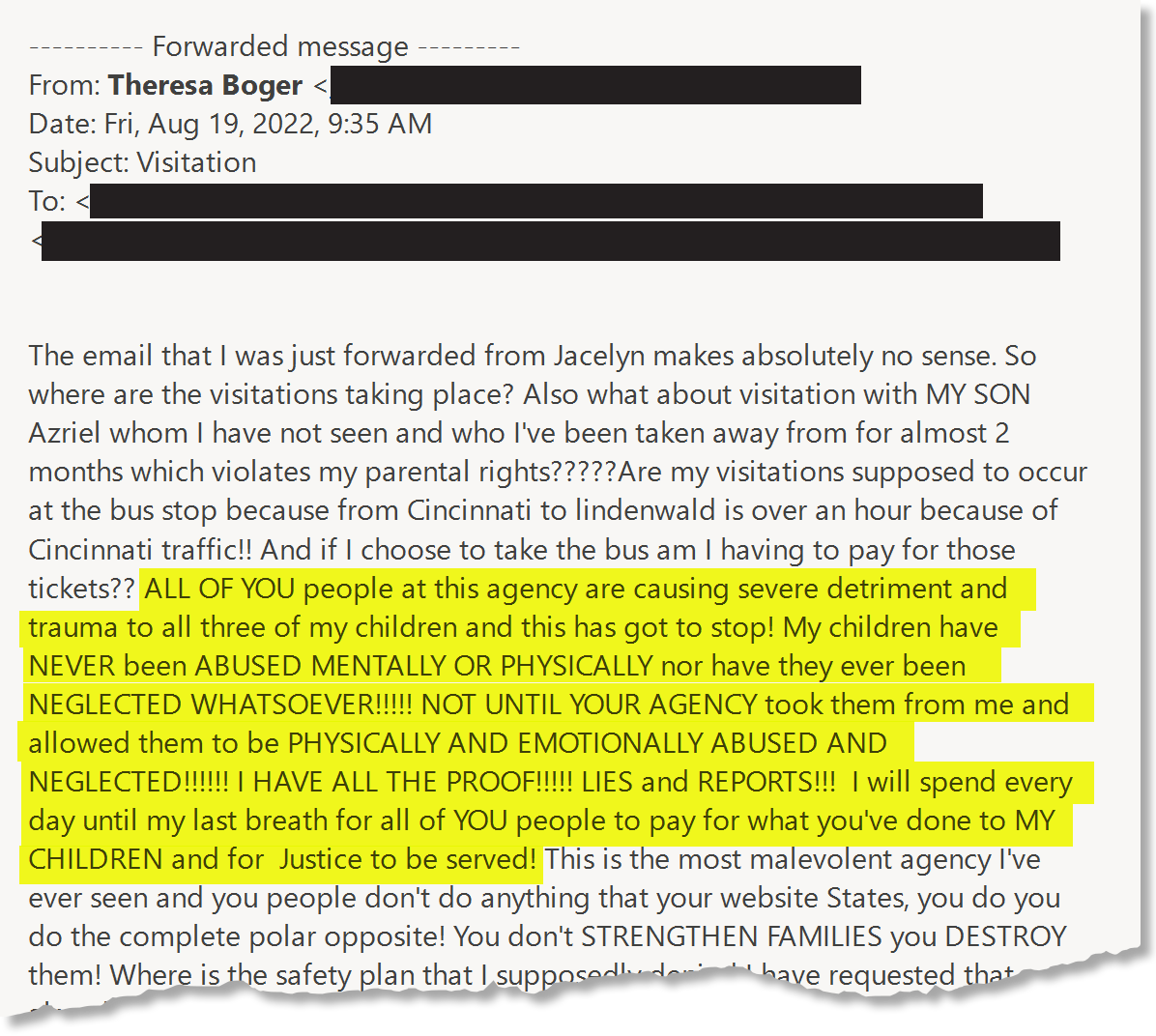

In an email dated Aug. 19 to multiple Children Services personnel, including McGaughey and her supervisor Stephanie McDaniel, Theresa wrote the following:

“ALL OF YOU people at this agency are causing severe detriment and trauma to all three of my children and this has got to stop! My children have NEVER been ABUSED MENTALLY OR PHYSICALLY nor have they ever been NEGLECTED WHATSOEVER!!!!! NOT UNTIL YOUR AGENCY took them from me and allowed them to be PHYSICALLY AND EMOTIONALLY ABUSED AND NEGLECTED!!!!!! I HAVE ALL THE PROOF!!!!! LIES and REPORTS!!! I will spend every day until my last breath for all of YOU people to pay for what you’ve done to MY CHILDREN and for Justice to be served!”

She continued, “You don’t STRENGTHEN FAMILIES you DESTROY them!”

McDaniel emailed Theresa shortly after saying that, due to their “strained” relationship, she was taking McGaughey off her case. She would arrange for a new caseworker the following week.

Theresa sent this Aug. 19 email to multiple Children Services employees, including caseworker Jacelyn McGaughey and her supervisor, Stephanie McDaniel.

On Aug. 25, protective services manager Barbara Cline emailed Theresa with an update. The agency was looking into a placement change for Azriel and needed to do a CANS (Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths) assessment “to know what is needed to best meet his needs.” Cline requested Theresa’s assistance and suggested that she and McDaniel meet with Theresa to address the issues in the case.

Cline also sent Theresa her case plan, which the agency should by law have created with her input and sent out a month earlier. The space for Theresa’s signature, which no one had ever asked her for, was empty. “Reason Signature Not Captured: Unavailable,” it read.

In the case plan, Children Services stated, as a condition of reunification, Theresa would have to enroll both herself and her children in therapy.

The irony was not lost on her.

“I wanted to die”

Whatever relief Azriel may initially have felt upon leaving Glouster did not last long.

He said he did not get along well with Jaime’s family — a state of affairs that extended to Josiah, who usually took their side. Azriel also felt guilty over his role in the removal and the pain it had caused his mother and sisters.

Before long, he was isolated and lonely. The rules his aunt set only made those feelings worse.

“I’d act out erratically and I’d like, punch stuff,” he said. “I’d hit wood and trees and punch stuff to make my anger to go away, because they secluded me. And every time I’d get home from going somewhere with my brother or anything, I’d go straight upstairs, ’cause I did not want to talk to nobody. I did not want to talk to them. I secluded myself in a room. I locked myself away in a room, depressed. I was depressed. I’d cry every night. I wouldn’t sleep. I’d go to sleep around 4 a.m. every night.”

“I’d hit something to feel something,” he said. “I’d hit something to feel pain.”

Jaime Boger declined to be interviewed, citing her family’s privacy.

A selfie of Azriel from early September.

Azriel tried to run away and made it as far as his grandmother Cheryl Boger’s house. He was barefoot because he’d left his shoes at home. Cheryl’s live-in boyfriend spoke with him about how he was feeling. After that, with nowhere else to go, he returned to Jaime’s.

The only relief Azriel experienced came when he smoked weed.

“That was the only time I could feel something,” he said. “And every time I’d smoke weed, I’d cry and just sit there and cry and cry and cry. I’d cry for hours at a time and just not stop crying.”

Azriel started expressing thoughts of suicide to the people around him.

“I wanted to die,” he recalled. “I did not want to be alive no more. I did not want to be stuck in that house anymore.”

He added, “I’d tell my girlfriend this and she’d be like, ‘Why? You know what would happen to me if I lost you?”

“I was like, ‘I don’t really think anybody would care because nobody cares about you until you’re dead.’ And she was like, ‘Well, I care. I will care and your mom will care and your sisters will care.’”

Azriel felt that Jayleigh was one of the few people he could talk to who made him feel like himself again. But the restrictions he said he faced at his aunt’s house limited the time he could spend with her. He said that made his feelings of isolation worse.

He said he told his aunt he had a plan for where and how he would die.

Still, he did not get therapy.

Theresa received periodic updates from Azriel and other contacts she maintained in Butler County. She passed on what she heard to Children Services, but it seems there was only limited follow-up.

Azriel claimed he hardly ever spoke with his caseworker. He said the one time he and McGaughey talked one-on-one, she threatened him with residential care if he didn’t stop smoking weed.

Apart from his drug use, he said they never discussed the issues he was having at Jaime’s and how he was feeling.

On Aug. 22, Azriel had a meltdown, prompting Jaime to call the police.

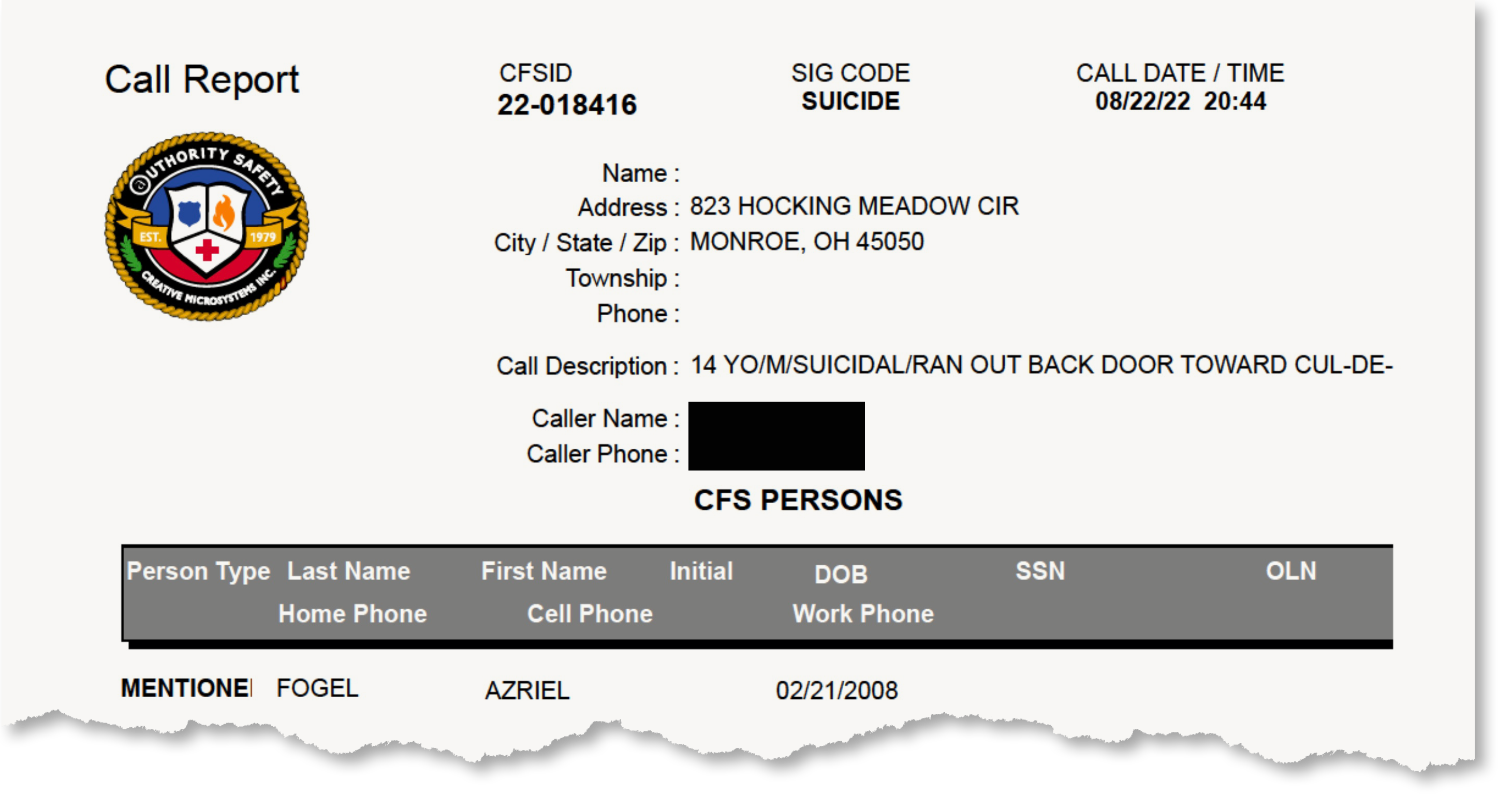

Part of the police report following Azriel’s meltdown on Aug. 22. The word “suicidal” is written in the call description.

“There was five of them,” Azriel recalled. “There was five because I was freaking out and I was punching the ground and I was hitting stuff and they were like, ‘You need to calm down. You need to calm down.’ And I was like, ‘What are y’all going to do?’And they were like, ‘If you don’t calm down, we’re going to have to take you to jail.’ I was like, ‘Take me to jail, I don’t care. I don’t want to live here no more. I don’t want to be here no more.’ And they were like, ‘Why? Can you tell me why?’ And I was like, ‘I get secluded in this house. I don’t get to go nowhere, I don’t get to talk to nobody.’”

One of the officers tried to help.

“He was like, ‘Well, just take some deep breaths, calm down a little bit, and we’re going to go down here and talk to your aunt,’” Azriel said.

But there wasn’t much else the officer could do. The police left without arresting Azriel.

The weeks dragged on. The counseling never came.

That’s a serious failure of the system.

“I think that’s a big deal that, following that, there were no services put in place, because that obviously presents significant safety issues where he could have harmed himself or someone else,” said American Counseling Association staff counselor Christa Butler.

Butler is well-acquainted with the child welfare process, having worked extensively with children services agencies in Virginia. She noted that arranging for counseling is fairly standard following agency intervention. Kids in the system need help processing both the removal itself and whatever stressors they may have encountered at home.

She acknowledged there are often wait lists, due to a nationwide, if not global, shortage in mental health practitioners.

However, “when a kiddo is expressing ideations to harm themselves or others — typically, that would kind of cause their name to rise to the top of that wait list,” she said.

Autumn comes

Theresa finally had a stroke of good fortune at the end of August: Her friend and neighbor Mimi Shuttleworth offered her a place to live.

“Once she got the eviction … she broke down and said, ‘I don’t know what I’m gonna do, I don’t,’” Shuttleworth recalled. “I said, ‘You know, don’t worry about it. I have a house that I started repairing, we just need to do some work.’ I said, ‘Trust me, my house is gonna be a lot better than that hole you’re living in right now.’”

This was a major shift. Over the summer, the threat of eviction had loomed large over Theresa as she prepared for her adjudication. Now, suddenly, that threat was gone.

Theresa and her boyfriend, Tyler Tingley, started helping Shuttleworth fix up the old house. Tyler’s industriousness impressed their new landlord.

“He’s doing just about everything. He’s helped hang drywall, what all, he’s helped clean. He’s helped put the duct for the new water tank,” Shuttleworth said at the time.

Then came another big change: a new caseworker.

Rebecca Inboden took over Theresa’s case from McGaughey around the time of the adjudication hearing in early September. She had more experience and was also a licensed social worker. Once she got involved, the family’s path to reunification started to become clearer.

Despite the hiccup at the adjudication — when the plan to get the girls home early fell through at the last moment — Inboden made arrangements for Rylenn and Everly to return to Theresa at the disposition hearing scheduled for mid-October.

She completed a home study and saw the room Theresa had put together for the girls in the house she was renting from Shuttleworth. One week after that, Inboden gave the OK for Rylenn and Everly to have unsupervised weekend home visits with their mom.

In the meantime, Theresa continued to pursue the grievance procedure against Children Services she had initiated some time earlier with the help of the Ohio Youth and Family Ombudsmen Office.

This was the last real chance she had to push back on the allegations against her. She hoped the agency’s internal review team would acknowledge the agency’s mistakes.

A system error had delayed her ability to file the grievance by several weeks, and it wasn’t until Sept. 12 that the Athens County Children Services quality assurance officer, Emily Kresiak, reached out to schedule a meeting.

“The meeting will give you the opportunity to have your voice heard and share your side of the story. It is meant to gather information from you and allow the caseworker to share her findings. We want to hear your perspective,” Kresiak wrote in an email.

The hearing took place behind closed doors at Athens County Children Services on Sept. 28. Theresa went with Becky Fulks, the advocate from the local domestic violence shelter. Her attorney, Jon Getson, declined to attend.

It’s worth noting that Athens County Children Services’ written grievance procedure allows parents to call witnesses. However, no one told that to Theresa.

Caseworker Jacelyn McGaughey, her supervisor Stephanie McDaniel and two women from the agency’s quality assurance team were in attendance.

According to Theresa, the hearing began with McGaughey recounting her version of the story. Theresa was then given the opportunity to share her own account. Fulks also had a chance to speak.

Theresa and Fulks were escorted out of the room afterward while McGaughey and McDaniel stayed behind.

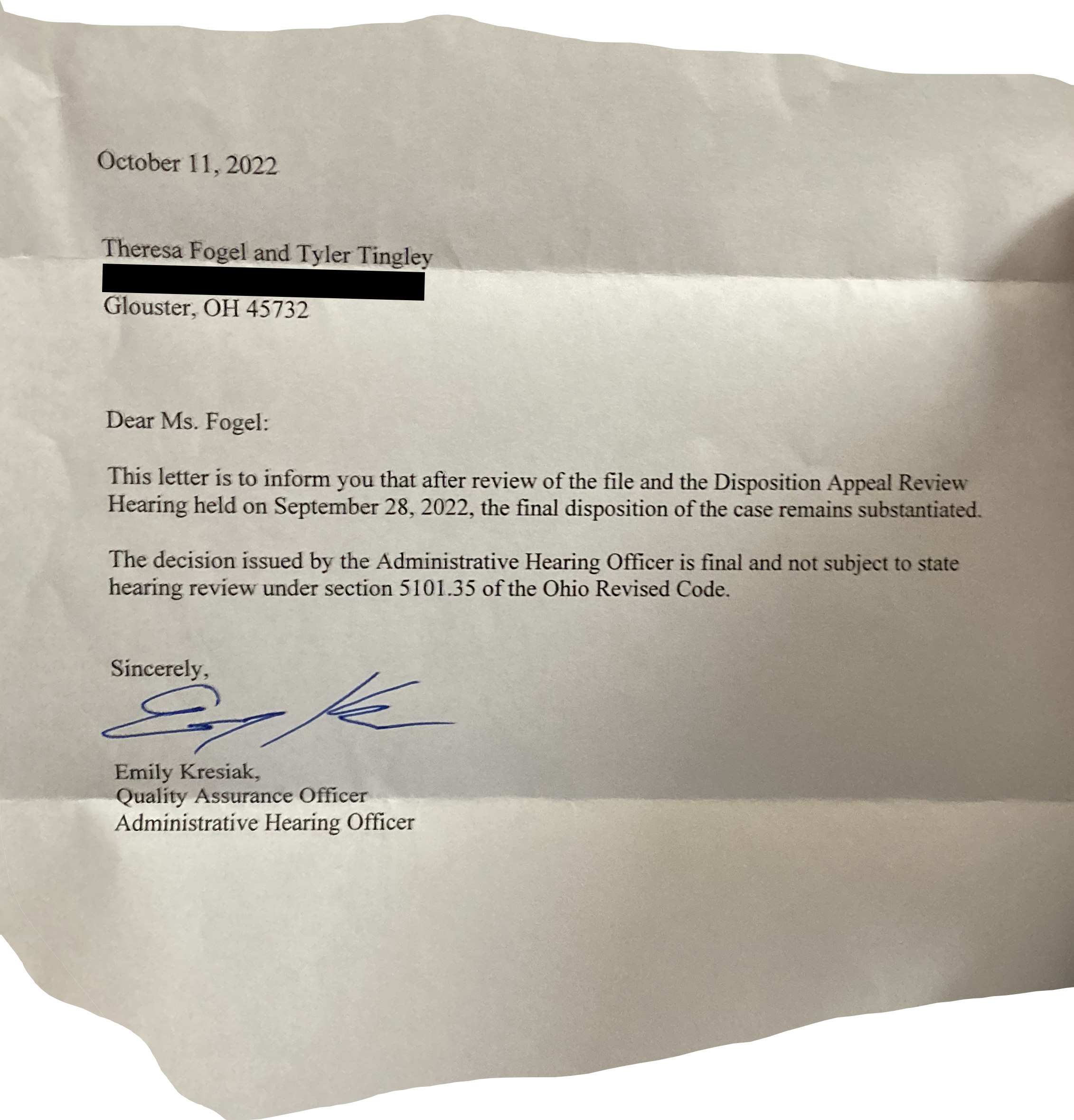

Two weeks later, Theresa received a letter from Kresiak. It read:

“Dear Ms. Fogel:

This letter is to inform you that after review of the file and the Disposition Appeal Review Hearing held on September 28, 2022, the final disposition of the case remains substantiated.

The decision issued by the Administrative Hearing Officer is final and not subject to state hearing review under Section 5101.35 of the Ohio Revised Code.

Sincerely,

Emily Kresiak”

The letter Theresa received from Children Services after her disposition appeal review hearing.

In other words, Children Services maintained its original assessment of Theresa’s family was correct. It admitted to no mistakes or wrongdoing at any point in the process. As far as the agency was concerned, everything its caseworkers had done up to that point was supported by the evidence.

Theresa never received any further clarification on what, exactly, that evidence was. And no evidence to support Children Services’ allegations has appeared elsewhere.

Diverging paths

During this time, Azriel continued to feel isolated and depressed in Butler County. He did see his mom once, when he went to Cheryl’s house for Rylenn’s birthday party. That was on Sept. 3.

He finally met Inboden, the new caseworker, for the first time in early October. She told him he would be leaving Jaime’s house soon — bound for a place called Foundations for Living.

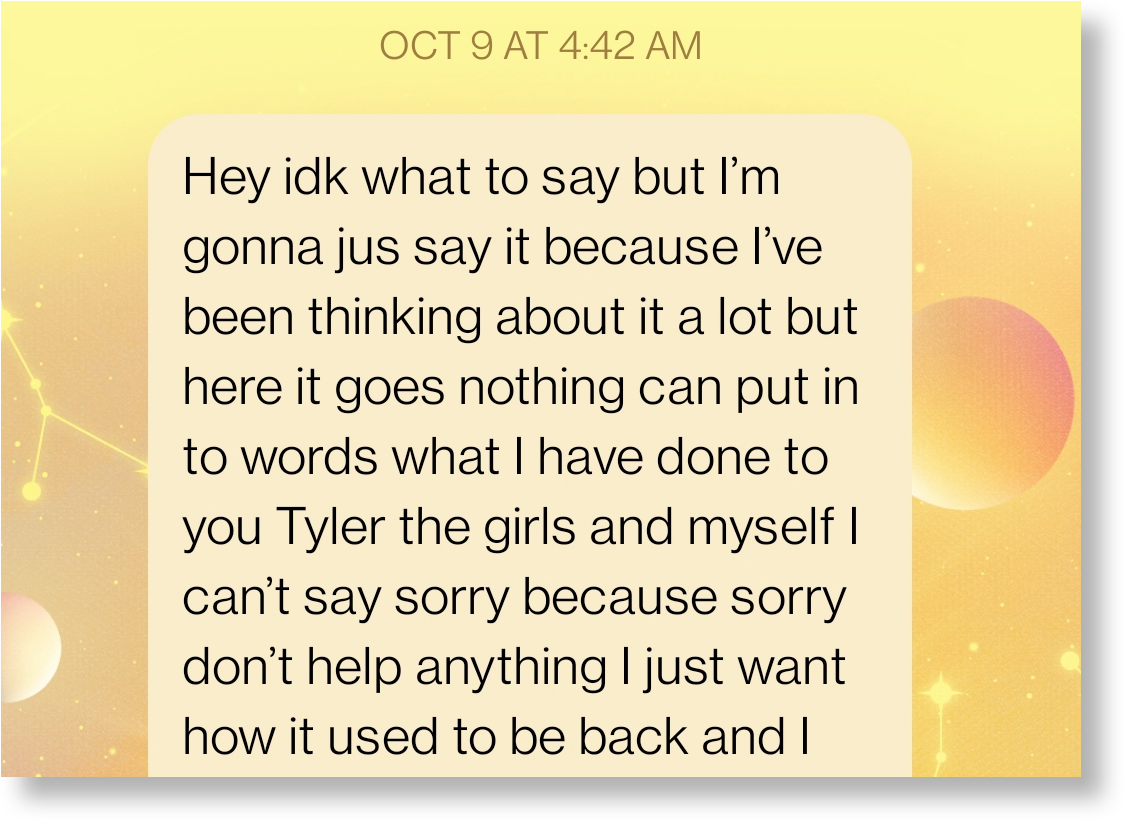

On Oct. 9, he sent a lengthy message to Theresa, which she read aloud to WOUB reporters at the house she rents from Shuttleworth:

“Hey. I don’t know what to say but I’m gonna just say it because I have been thinking about it a lot. But here it goes.

Nothing can put into words what I have done to you, Tyler, the girls and myself. I can’t say sorry because sorry don’t help anything. I just want how it used to be back, and I want you happy, and to be able to wake up and smile and say today is gonna be a good day. I want you to wake up and look around and say there are no problems. I just want the best for our family, and we all just need time to grow and heal.

But I’m sorry for everything I have done, and I know that my love for you and Tyler and my brother and my sisters is all from my soul and my heart. I just want us to be happy. And I know that I can’t take none of it back, because it already happened. But I would if I could in a heartbeat. And I want to say sorry to Rylenn and Everly. I put them through something no little girls should go through and I can’t take it back. I blame myself for all of it, and I know that you’re gonna say it’s Siah’s fault, but it’s mine too.”

Azriel wrote several more lines reiterating his regret.

“And mom, I’m sorry I’m not the son you dreamed of. But you told me no one is perfect and told me everyone has that one moment in their life, and that stuck with me all these years,” Theresa read, her voice cracking.

The beginning of Azriel’s lengthy text to Theresa on Oct. 9.

Theresa’s disposition hearing took place on Oct. 18, 115 days after her children were removed. This time, her attorney, Jon Getson, contacted a handful of witnesses, including Sue McGee, a neighbor, to testify on Theresa’s behalf. Their purpose was to convince Judge Zach Saunders that Theresa should regain custody of the girls.

But the witnesses’ presence turned out not to be necessary. Children Services was happy to let the girls go home.

Saunders returned custody to Theresa and gave the agency an order of protective supervision — essentially, a mandate to continue checking in on the family.

Rylenn and Everly were back in Glouster that weekend. Theresa had converted the house’s old living room into their bedroom and filled it with toys, stuffed animals, books, games and activities.

“That room stretches from the whole left side of the house to the right side of the house. That’s something, that room is,” Shuttleworth said.

In all, Rylenn and Everly had been separated from their mother just shy of four months.

Theresa was relieved to have them home, but it did not make up for all the stress, uncertainty and frustration she continued to endure as a result of Children Services’ intervention. She still spent every day under the agency’s thumb because of what she knew were false accusations.

She was tired of having to convince other people she was a good mother. And she was upset the agency kept failing to address Azriel’s needs while simultaneously trying to tell her how to live her life.

“Why are you — why, around every corner, are you trying to manipulate our lives? Nothing’s even happened. You have no evidence of anything. And you’re doing this — to spite me? For what?” she said.

Zero to one hundred

As it turned out, Foundations for Living — Azriel’s new placement — was a secure residential treatment facility for kids with severe behavioral issues. Many of the other residents came from juvenile detention.

Azriel still had not received any counseling since the removal. In spite of this, Children Services informed the staff at Foundations that Azriel’s placement was necessary because he had not succeeded at a lower level of care.

It’s not clear why the agency told this to Foundations. Azriel had been in therapy once before, but that was before the family moved to Glouster, long before the agency’s involvement. Since his removal into Children Services’ custody, he’d seen no one.

Placing Azriel directly at Foundations was a risky move. There are reasons why treatment providers are encouraged to pursue lower levels of care before considering lockdown residential treatment.

“One of the number one rules in counseling is to do no further harm,” counselor Christa Butler explained. “And the potential for placing a child, or anyone, in an inappropriate placement is that it could be potentially harmful to them, and potentially present more challenges than solutions to why they’re seeking treatment in the first place.”

Put another way: A lockdown facility can cause even more trauma. Like child removal, it’s a high-intensity intervention with potentially serious side effects. That’s why it’s important to try a lower level of care first.

But in this case, Azriel went straight into the deep end of psychiatric treatment.

He realized what kind of facility it was as soon as he walked inside. He was nervous. But Inboden had told him, if he behaved well, he would only be there for 45 days.

“I went into this room and they asked me a bunch of questions like, ‘Why do you think you’re in here?’” Azriel recalled. “And I was like, ‘My mental health, basically my depression, my anger issues, my PTSD, my anxiety and stuff like that.’ And then they took a picture of me.”

Then he got some bad news.

His counselor said Foundations no longer had a 45-day program. He’d be there for a minimum of five months — longer than he’d been at his aunt’s.

“I broke down,” Azriel recalled. “That s***, it broke my heart.”

Azriel and the other kids at the facility were constantly under surveillance. Their sleep and breathing were tracked at night. Azriel’s room, which he shared with one other boy, had a door like a jail cell. Of the four showers in the bathroom, only one worked, and the water was cold.

“Imagine taking cold showers for a month straight,” Azriel said.

Just getting the water to run was a challenge.

“You had to hack it,” he recalled. “So you’d have to hit it, hit the faucet thing, and then you’d have to turn it a little bit, and then it was like, ‘click,’ and then it’d come on.”

Most of the heaters were also broken. Every door was locked and required a staff member to open. Shoelaces and hoodie straps were banned. Phone calls were limited to 10 minutes.

Despite being a high-security facility, there were dangers. Kids got into fights. Azriel said he was punched repeatedly in the arm after beating someone in a video game. His roommate kept a shank made from the sharpened clip of a pen. According to Azriel, he’d wound up in juvie for jacking cars and jumping people.

Theresa was livid when she heard all this. “I’m getting him out of there. I don’t care what I have to do,” she declared.

But like most other things in the child welfare process, it was out of her control.

Foundations for Living did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Azriel was relieved when his roommate was eventually transferred to another room. He and his new roommate got along better.

“We were both in there for mental health issues, so we could relate to each other, and we liked working out and exercising,” Azriel said. “So that’s what me and him did. We did pushups every night, and situps, and just got along.”

Therapy is not supposed to be a punishment.

Nevertheless, Azriel had the sense he had to earn his way out of Foundations. He was told that if he showed good behavior, he could leave sooner. He avoided getting into fights and did as he was told.

Homecoming

Judge Saunders scheduled the first review hearing for Nov. 22. In child welfare cases, these hearings occur regularly after the disposition to evaluate how the family is progressing on the case plan.

Depending on how things go, the judge can restore custody to the parent, but much of that hinges on what the caseworker says and how effective an advocate the parent’s lawyer is. If enough time has passed, the judge can also remove parental rights permanently and put the kids up for adoption.

Theresa’s case plan, derived largely from unsubstantiated allegations, had always seemed like more of an afterthought than a genuine strategy for reunification.

Fortunately, Inboden herself seemed to believe the family had little need of her services. It was therefore not altogether surprising when she hinted that Azriel’s custody status might change at the first review hearing.

Theresa relayed her conversation with Inboden to Azriel, who was still at Foundations, and told him if he continued to do well there, he would be out in time for Thanksgiving. She was planning a feast.

And then, with little fanfare, it was over.

Children Services did indeed recommend returning custody of Azriel to Theresa at the review hearing, and the judge agreed. It again had an order of protective supervision, but at that point, it was hard to imagine what the agency would even be looking for.

Theresa took this photo of Azriel’s bruised arm the day he returned from a residential treatment facility.

Inboden drove to Foundations that day to pick up Azriel. Now that custody had changed, he was free to go. His stay at Foundations had, in fact, lasted about 45 days.

In total, he was separated from his mom for 150 days.

“When I first came in, Arlo was sitting in here,” Azriel recalled of his return home. “I said ‘Arlo,’ and he turned around real quick, and you know how when an army man comes home and sees his dog that he’s had from when they were a puppy, and he was crying. … That’s my best friend. I love him. I was so happy to be home. So happy.”

“And when I walked in, they already had all my stuff and Tyler helped me get all my stuff inside, and stuff like that. Rebecca (Inboden) came in here for a minute and then she said, ‘Oh, I can’t talk right now, I got to go, I got to go home.’ And then she left. I got situated. I told my mom what I just told y’all about the residential facility, and then my mom was like, let’s go up and see your room. And I was like, OK. And then when I walked in my room, my girlfriend was sitting on my bed.”

Theresa got him right into counseling.