A banner that hung outside the main office of Athens County Children Services in April thanking those who call the agency to report suspected abuse or neglect. [Theo Peck-Suzuki | WOUB/Report for America]

Chapter 7

Changing the system

As painful as those months in the child welfare system were for Theresa and her children, none of their experiences struck experts as unusual. Unjustified removals, mishandled cases, and rubber-stamped court proceedings are commonplace in this area of the law.

In fact, what distinguishes Theresa’s case is not what went wrong, but how quickly it was resolved.

“Ms. Fogel specifically stated on the record that she wished for three of her children to come home,” her attorney, Jon Getson wrote to WOUB. “I was able to achieve this goal for her in a timely manner, due in large part to my zealous advocacy throughout her case. Although it was unfortunate that these children were removed, Ms. Fogel’s case is one of the rare cases in which her children were returned within a very short time frame.”

If spending 150 days without one’s child on the basis of unsubstantiated allegations can be considered “very short.”

Getson’s assessment may seem out of touch considering just how excruciating those 150 days were for Theresa and her children, but in the context of the child welfare system, he’s not wrong. Those 150 days — and all the stress and trauma therein — were, in the eyes of the system, a brief stint with a happy ending.

Experts say that’s exactly why the system needs to change.

Jennifer Renne of the American Bar Association has spent over 30 years in the American child welfare system. She has written three books about the system and trains attorneys and judges on how to improve outcomes for families in juvenile court.

She said a culture of dysfunction pervades the entire system.

“It’s not that social workers or judges or lawyers want to shortcut due process or remove kids,” she said. “It’s just the way the system is set up. And so we need interventions like a framework for thinking about, ‘What is safety? What do we really need to do before, God forbid, we have to remove a child?’”

Sometimes, the outcomes are far worse than Theresa’s. Cases drag on for years. Kids suffer grievous abuse in foster homes or group facilities. Parents lose custody of their children forever.

The child welfare system exists ostensibly to keep kids safe, no matter what. The problem is this: Taking kids from their parents is often more harmful than whatever danger they faced in the first place. And no one is there to protect kids from their protectors.

Efforts are growing to fix the system’s many issues.

Pockets of the United States are experimenting with new ways of handling abuse, neglect and dependency cases. Awareness is growing of the importance of providing resources to low-income families, which experts say can significantly lower both the prevalence and duration of child removals.

Those changes happen when people — whether they be lawyers, judges or everyday citizens — take a more active interest in how their communities address child welfare.

Athens County Juvenile Court Judge Zach Saunders, who oversaw Theresa’s case, is relatively new to the bench. He said if things need to change in his courtroom, he would make it happen.

“That’s what I took this job for, was to change this office,” he said.

A call for reform

University of Michigan law professor Vivek Sankaran has written extensively on the need for change in child welfare. At the top of his priority list: the removal process and the legal scaffolding around it.

“You have to have a system where parents, with their lawyers, soon after this removal happens, or before it happens, should have a chance to quickly challenge the removal in a full, robust hearing,” he said. “If you wait for the adjudication hearing, it’s just too late.”

Sankaran said the structure of the court process makes it far too easy to remove children, and the judicial safeguards kick in too late, if at all.

Yes, caseworkers are only supposed to remove for “immediate or threatened physical or emotional harm” — but that seemingly high standard is diluted by the fact they only need to show probable cause to get the judge to sign off.

Put another way: Caseworkers do not need to see an immediate threat of harm to put a child in foster care. They can put a child in foster care when they think there might be such a threat to pass a probable cause test.

It’s a high level of uncertainty for such a consequential decision.

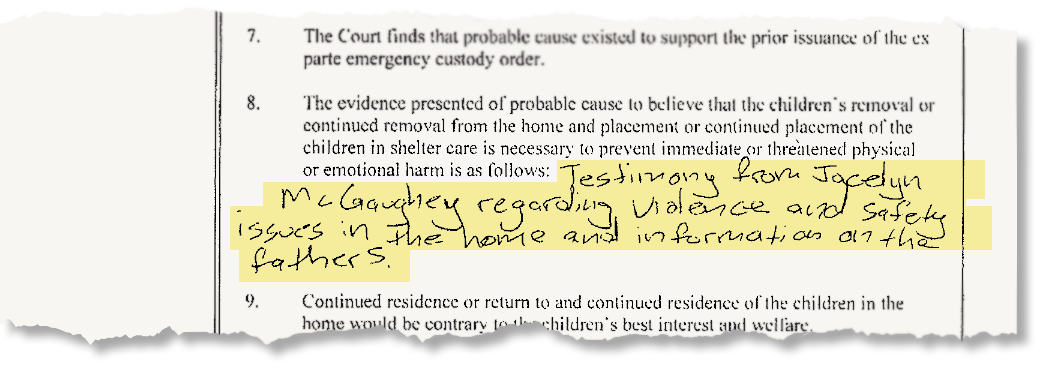

This was the summary of the evidence used to remove Theresa’s children. Caseworker Jacelyn McGaughey’s testimony was mostly hearsay based on her conversation with Theresa’s sons, Josiah and Azriel.

Cuyahoga County public defender Denise Ferguson, who has represented parents in child removal cases for many years, said raising the standard at shelter care hearings from probable cause to clear and convincing evidence would “change things immensely.”

“Then you’d actually get people doing a more thorough investigation,” she said.

In criminal law, probable cause is the standard required to obtain a search or arrest warrant. Sankaran argued that’s too low for child removal, given the potential for it to inflict lifelong trauma on children and parents.

Moreover, a defendant in a criminal case will have a lawyer starting with their first hearing. Parents in juvenile court often don’t, even though state law may give them a right to counsel, as it does in Ohio.

This is due in part to the timeframe commonly set by states: In Ohio, there can be no more than 72 hours between removal and the first hearing. Courts often can’t find appointed counsel that quickly. And because few public defender offices in Ohio take on juvenile court cases, appointed counsel is all most judges have to work with.

Theresa’s case shows exactly what can happen when parents don’t have an attorney at this first hearing. With no one there to cross-examine her caseworker, crucial facts of the case went unacknowledged and the lack of any apparent investigation went unaddressed. Potential avenues for resolving the case quickly went unexplored.

Sankaran pointed to unified public defender systems as one way to address the issue of parent representation. Under that model, the state pays for public defender offices, rather than the county (which is how it works in Ohio). This way, parents always have an attorney right from the start. He said Washington state, Colorado and Arkansas have seen some success with this approach.

Jennifer Renne of the American Bar Association said different parts of the country are experimenting with a variety of models to ensure parents have adequate representation as soon as their kids are removed. But she agreed the best approaches tend to be in-house, meaning something like a public defender’s office.

“The contract attorney system typically doesn’t work,” she said, because those lawyers can’t be located in time for the hearing.

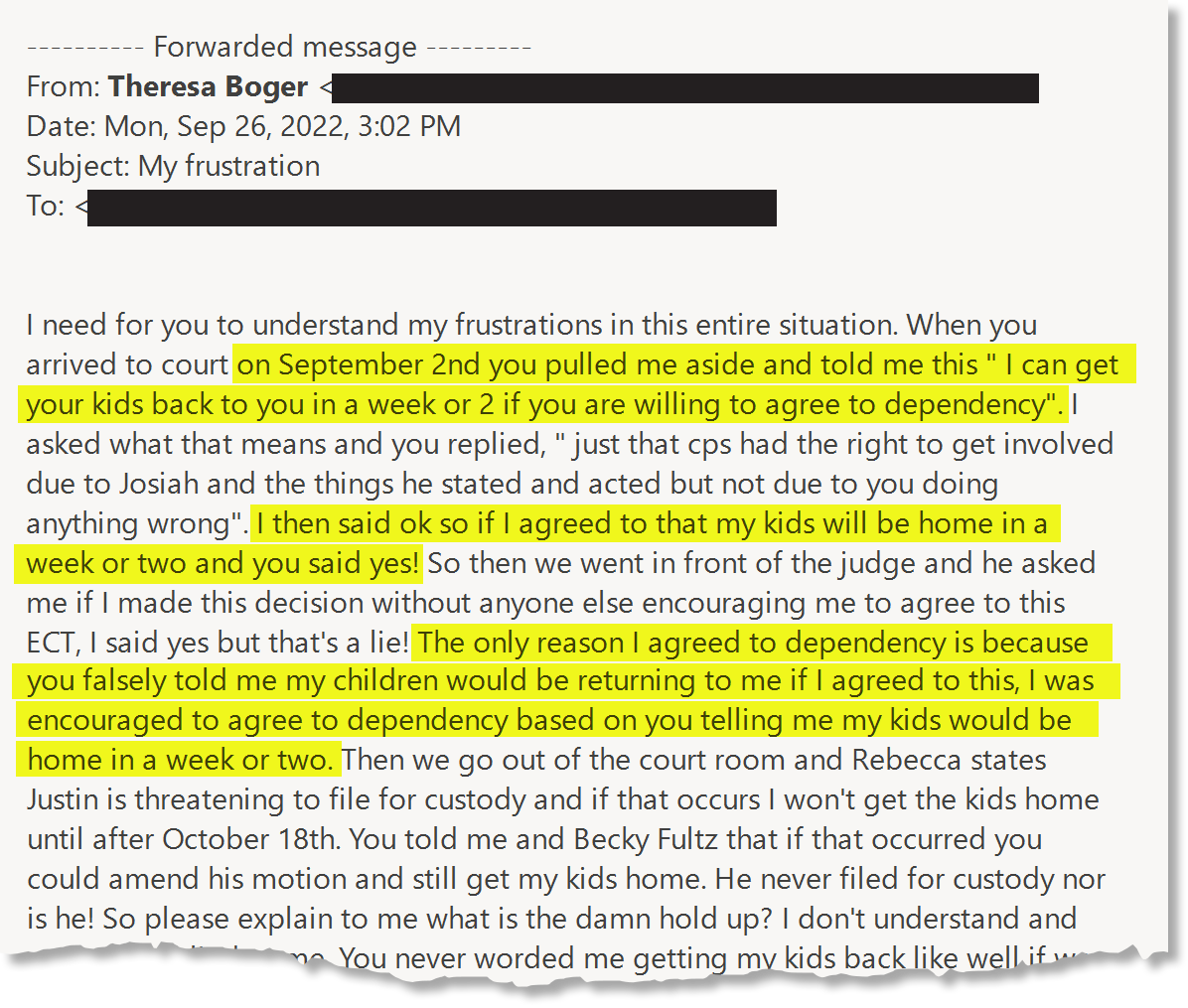

Theresa’s issues with her contract attorney, including what she believed was poor communication, echoed systemic problems identified by experts.

There’s another big blind at the shelter care hearing: what the children actually want. Kids rarely even attend the hearing, much less give direct input on the proceedings. Throughout the process, their lawyers — typically guardians ad litem appointed by the court — often decide for themselves what’s in their clients’ best interest. Sankaran said that’s a problem.

“We can’t let children’s lawyers off the hook, because in the overwhelming majority of cases that I’ve handled, children don’t want to be separated either from their parents. And one would think that in a system that was functioning, their lawyers should be challenging the allegations as well in those cases,” he said.

Renne said she would be “retired and dead” before the standard of proof for child removals rises above probable cause. But she said other changes could have a big impact on the initial hearing.

“There are things in federal and state law that are supposed to provide protections at the shelter care hearing,” she said. “The problem is, the implementation of those laws is ineffective.”

A prime example is something called “reasonable efforts.” Agencies are legally required to show the court they made reasonable efforts to prevent the removal of children. Otherwise, they can lose their federal reimbursement for placing those particular kids in foster care. According to Renne, however, this tends to be little more than a formality in many juvenile courtrooms. Judges, and often parents’ attorneys, just rubber stamp the agency’s efforts.

That allows agencies to conduct removals that realistically aren’t justified.

A learning curve

According to Renne, the reasonable efforts requirement is one of many examples in child welfare where courts don’t always adhere to what’s written in the law. She said that usually isn’t because of any ill intent.

There’s a learning curve for judges. Juvenile court is, in many ways, more demanding because they can’t just “call balls and strikes,” Rene said. And few judges stick around long enough to learn the ropes.

“If you’re a juvenile or family court judge, you need to know the law, you need to know the facts, you need to know what the agency’s doing, not doing, why aren’t they doing (it),” Renne said. On top of that, judges need to become intimately familiar with the histories of the families in their courtroom. That’s much different from criminal law.

Vivek Sankaran, the Michigan law professor, said courts across the country have become complacent about enforcing the rules.

“How come more removal appeals aren’t taken to their appellate courts to look at these cases?” he asked. “You think of the jurisprudence in criminal law, which is so extensive. It’s extensive because of appellate cases, right? We have Miranda because somebody challenged that all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court and established this fundamental right. And yet in most states, I doubt that there’s a robust appellate practice as it relates to family defense.”

He said he doesn’t see that in his home state of Michigan and doubts it happens in Ohio either.

That might be partially because, in the case of an appeal, Children Services keeps the kids for another six months or more while the appeal makes its way through the process. This is a disincentive for parents to pursue an appeal.

Exacerbating all of this is that everything about the child welfare system is hidden from public view, which makes it next to impossible for outside observers to see what’s going on.

“The program that Children Services uses (for case management) — I mean, I think you need to have clearance higher than the president of the United States to have access to that,” joked Jane Novick, the former director of the court-appointed special advocate (CASA) program in Montgomery County.

“That is a frightening thing,” she added. “I don’t care how great you are. Nobody is perfect. Everybody needs somebody independent, you know, to be able to look over things.”

CASAs are meant to be exactly that: an independent voice in the juvenile court process whose reports to the judge offer a separate opinion on a family’s situation. But Novick said her CASAs were seldom successful in pushing back against the agency.

Defenders of the child welfare system highlight that caseworkers do, in fact, face scrutiny from both internal and external sources.

The Ohio Department of Job and Family Services’ Office of Families and Children takes on much of that responsibility. This office monitors county child welfare agencies to ensure they are compliant with state and federal law. The process includes annual reviews to evaluate agency performance and look for areas of improvement, as well as targeted reviews of specific cases in the event of a child fatality or when there is a question of noncompliance.

On top of that, the new state Youth and Family Ombudsmen Office gives parents a way to file a complaint directly with the state.

Individual agencies have a formal grievance procedure for parents who feel they have been wronged, in which a quality assurance officer arranges an administrative review hearing with the parent and caseworker. Theresa did that in her own case.

The federal government, which helps fund child welfare agencies, also conducts its own reviews every three to five years. These audits evaluate how agencies are spending federal reimbursement money and also include specific case reviews.

In the most recent federal review, which took place in 2017, Ohio’s child welfare system failed to meet a significant number of benchmarks regarding child safety and wellness.

However, the report also stated: “Ohio and its county, court, and community partners have shown their commitment to meet the changing needs of families and children who become involved in the child welfare system. They are well-positioned to improve outcomes in the areas found.”

At the end of the day, none of this oversight succeeded in catching the lapses that occurred in Theresa’s case — and there were several.

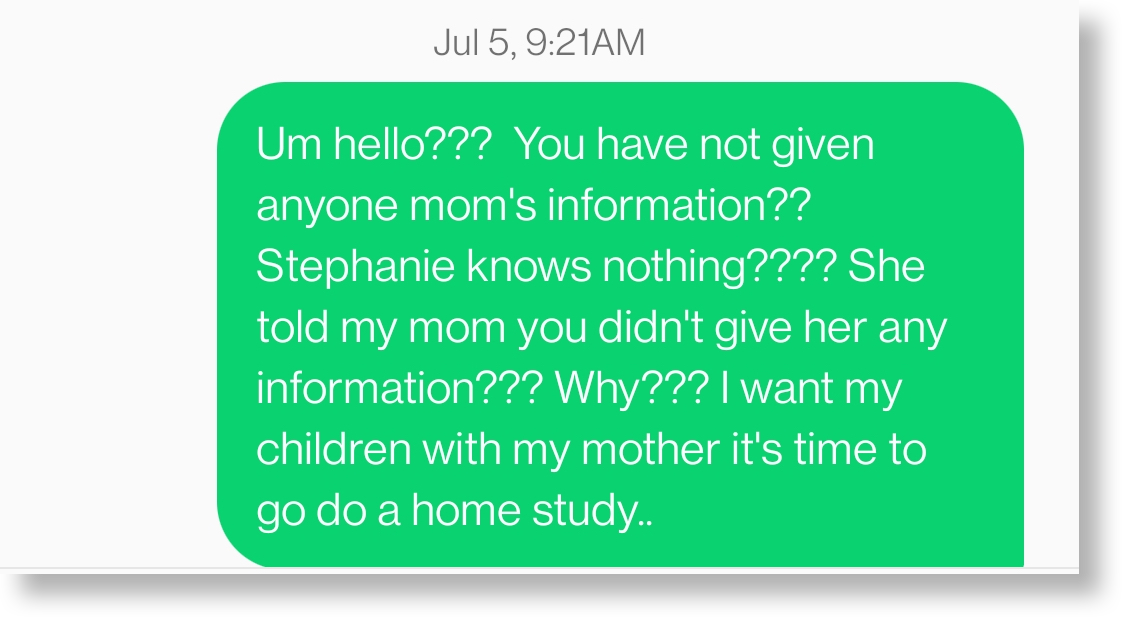

For example: Why weren’t the girls immediately placed with their grandmother, Cheryl Boger? Per section 2151.314 of the Ohio Revised Code, this is supposed to happen right after the shelter care hearing. Moreover, the boys went directly to their aunt’s house. But the girls endured a month of foster care, during which they suffered physical abuse.

Theresa sent this text to caseworker Jacelyn McGaughey the week after her children were removed. It was neither the first nor the last time Theresa asked that her daughters go to their grandmother’s home.

Then there was the elusive case plan, which should have been developed with Theresa, signed by her and delivered to her by July 27 at the latest. It was instead sent to Theresa in late August, she had no input in creating it and she did not sign it.

There was also the thin discovery — providing little evidence to support the allegations against Theresa — which her attorney did not receive until after the original adjudication date.

Some of these may seem like technicalities, but they are still the law. Rules like these keep government agencies in check. When they aren’t enforced, those checks weaken or even disappear.

Even after Theresa filed a grievance with both Children Services itself and the Youth and Family Ombudsmen Office, the agency stuck to its course. When offered the chance to modify its stance following an administrative review hearing, Children Services did not acknowledge making any errors in its initial assessment.

Cases like Theresa’s are why many critics argue the current oversight systems just don’t work — either by complacency or design. Some point out internal oversight is not particularly good at catching systemic problems.

Would any administrative review, for example, flag that Theresa did not have a lawyer at her shelter care hearing? Few have a lawyer at that point. And what oversight would cite the vague definition of dependency in the Ohio Revised Code and suggest this needs fixing?

Richard Wexler, executive director of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform, believes the answer to these issues is not more oversight but more transparency. For him, that starts with eliminating the use of closed hearings in juvenile courts. Ostensibly, the courts are closed to safeguard children’s privacy, but Wexler isn’t convinced.

“They’re all phony arguments designed by people who don’t want you to see what a terrible job they are doing,” he said.

“The reason for (closed courts) is not to protect children. It’s to protect the system. And over and over again, by the way, when courts were opened, one-time skeptics became converts and strongly endorsed them.”

Wexler pointed out that states that have opened up juvenile courtrooms haven’t seen children’s privacy compromised.

“The courts have been open in New York for 25 years. Almost as long in Minnesota. Even longer in Oregon. It hasn’t happened,” he said. That’s partly because the law still prohibits the names of victims from being published.

Jennifer Renne, the child welfare expert with the American Bar Association, said judicial leadership can also make a difference.

“There are things they (judges) can do on the bench in terms of a specific case, and giving it the time it deserves, making sure that legal counsel is appointed and prepared, and then things they can do off the bench to participate in systemic change,” she said. “In fact, that’s the only way we’ve made the progress that we have is that judges, attorneys, court administrators have been generous with their time and their talents to solve these complex problems.”

The obligation to improve the court system is one Judge Saunders said he takes seriously.

“You come in this court, you get a fair shot. And if they (the parents) don’t believe that the allegations are there, they have that right to put forth their evidence. And I will tell you, and I know, that I have an oath to uphold the constitution and the laws of Ohio, but that also means that they’re going to get their due process in this court.”

Better representation

Of course, it’s not exclusively the judge’s job to ensure the rules are being followed. There’s a lot that happens in a case outside the normally scheduled hearings, where judges have no involvement.

That’s where parents’ attorneys come in.

An effective attorney can challenge an agency on reasonable efforts, failing to file a case plan or not intensively seeking a kinship placement. That’s not the only difference a good lawyer can make.

Before there’s even a shelter care hearing, connecting parents with strong legal representation can change everything.

“There are pockets of the country that have what we call pre-petition legal representation,” Renne said.

This system provides parents with legal assistance as soon as a call to a children services agency gets screened in. The attorneys help manage the legal side of everything from domestic issues to housing insecurity to education.

“Are there special needs? Are there school disciplinary issues? Let’s get an education attorney to support (parents),” Renne said. The point is to stabilize the family before removal is even on the table.

Renne said the big issue with pre-petition representation is funding. Data is only just beginning to come in on how cost-effective it is in the long run. But foster care has already proven itself to be quite expensive and damaging.

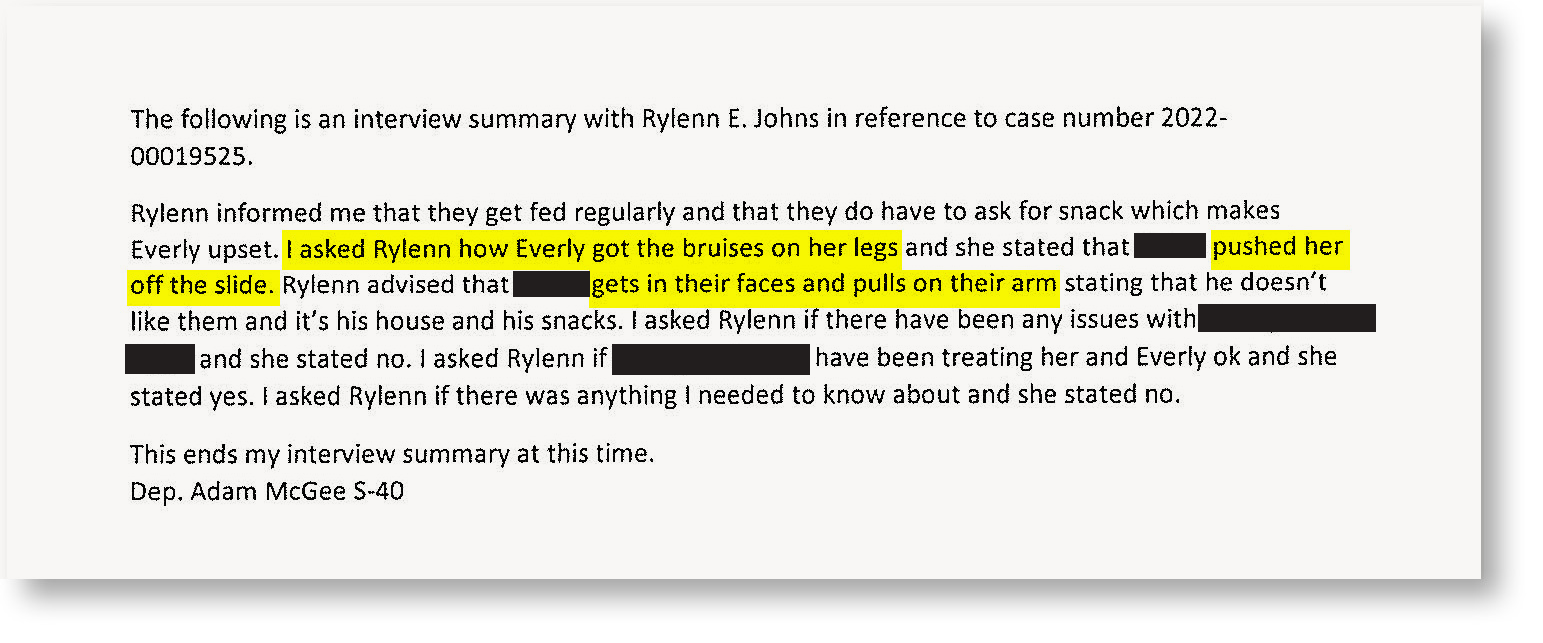

The report from Muskingum County Deputy Alex McGee confirms that Theresa’s daughters, Rylenn and Everly, were physically abused at their first foster home.

Renne also stressed that in most child welfare cases, the family in question is actually struggling in one way or another.

Cases like Theresa’s, where the accusations almost totally disintegrate under scrutiny, are rare in Renne’s view. But just because a family has a problem does not mean removal is a good solution or the agency should have all the power once the kids are in the system. That’s where having a strong legal advocate is once again critical.

Reform advocate Richard Wexler pointed to a strategy called interdisciplinary family representation he said has shown promise.

“The family gets a defense team,” he said. “A lawyer from an institutional provider with a reasonable caseload. A social worker employed by that defense lawyer’s firm, because that’s someone who could craft a good case plan, an alternative to the cookie cutter nonsense that is typically handed out by child welfare agencies. And sometimes, a third member of the team: a parent who’s been through the system herself.”

“When you do it that way — and there’s been a comprehensive study of this, New York City has it on the widest scale — there is a dramatic drop in time spent in foster care and no compromise in child safety.”

One of the central conditions of Theresa’s case plan, which was made without her input, was that her children go to counseling. Ironically, Theresa had been asking Children Services to arrange counseling for her children long before the agency filed the plan.

Renne also believes children should have their own attorneys under a traditional attorney-client model, where the attorney advocates for what the child wants. What most children in the system currently have is a guardian ad litem. That’s not the same thing.

“The best that a GAL can do is advocate for what they think is in the best interest of the child, and that’s an important distinction,” Renne said.

Attorneys in a criminal case can advise their client, but ultimately, they do what their client tells them to do. If their client wants to plead not guilty and go to trial, the attorneys will help them do that, regardless of what they personally think is in their client’s best interest.

GALs aren’t like that. If a child wants to go home, and a GAL disagrees, the GAL can make whatever recommendation they feel is best.

Defenders of the system point out that this is because kids often want to return to their abusers, even if the situation is extremely unsafe. But critics say that’s not a reason to take away their voice in court.

Azriel articulated his needs regularly to his mother, but the system struggled to provide effective support.

Often, Renne said, the people best equipped to explain what children want and need are children themselves.

Feeling powerless can also have consequences for children’s mental health. Renne said she knows of kids becoming suicidal despite having positive relationships with their GALs because the system was failing to identify what they actually needed.

Shifting focuses

Wexler argued the tendency of child welfare agencies to over-remove is deeply rooted in their history. He traced some issues to the medicalization of child abuse, which began through the work of pediatrician Dr. C. Henry Kempe in the 1960s.

Kempe, who is widely regarded as a pioneer in child welfare, published an influential paper in 1962 on what he termed “Battered-Child Syndrome.” That paper, along with Kempe’s subsequent work, are credited with spurring legislative action on child welfare. Laws such as the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) passed in 1974. CAPTA has been revised several times since and still funds child welfare agencies today.

Wexler said Kempe viewed child abuse as a medical condition of the parents. In Wexler’s view, this opened the door to a very specific kind of response: reforming parents through things like therapy and parent education. Wexler said that idea — that child maltreatment is a medical condition responsive to treatment — has carried over into every area of child welfare, even when it’s not appropriate.

“So therefore, we think of a poor person who is too poor to have enough food in the home — there must be something wrong with you, something wrong with your character, amenable to counseling and therapy,” he said.

Wexler’s point is not that people who mistreat children don’t need therapy. It’s that often, there’s something else going on external to the parents that leads to the maltreatment.

“There’s been study after study after study in recent years showing that even small amounts of additional money reduces what agencies call ‘child neglect,’” he said. “For example, raise the minimum wage by $1 an hour, you reduce what agencies call ‘neglect’ by 10%. There are a whole series of similar studies. But that’s not the culture” of child welfare.

Even those far less critical of the system than Wexler acknowledge it has historically been too punitive.

“The perverse thing is that, for decades, federal funding has incentivized removal into foster care, because that’s all the feds would pay for for a long time,” said Scott Britton, assistant director of the Public Children Services Association of Ohio. “Finally, we have this federal change that allows us to use those federal dollars for prevention to keep kids out of foster care, and that is the beginning, I think, of a really exciting change.”

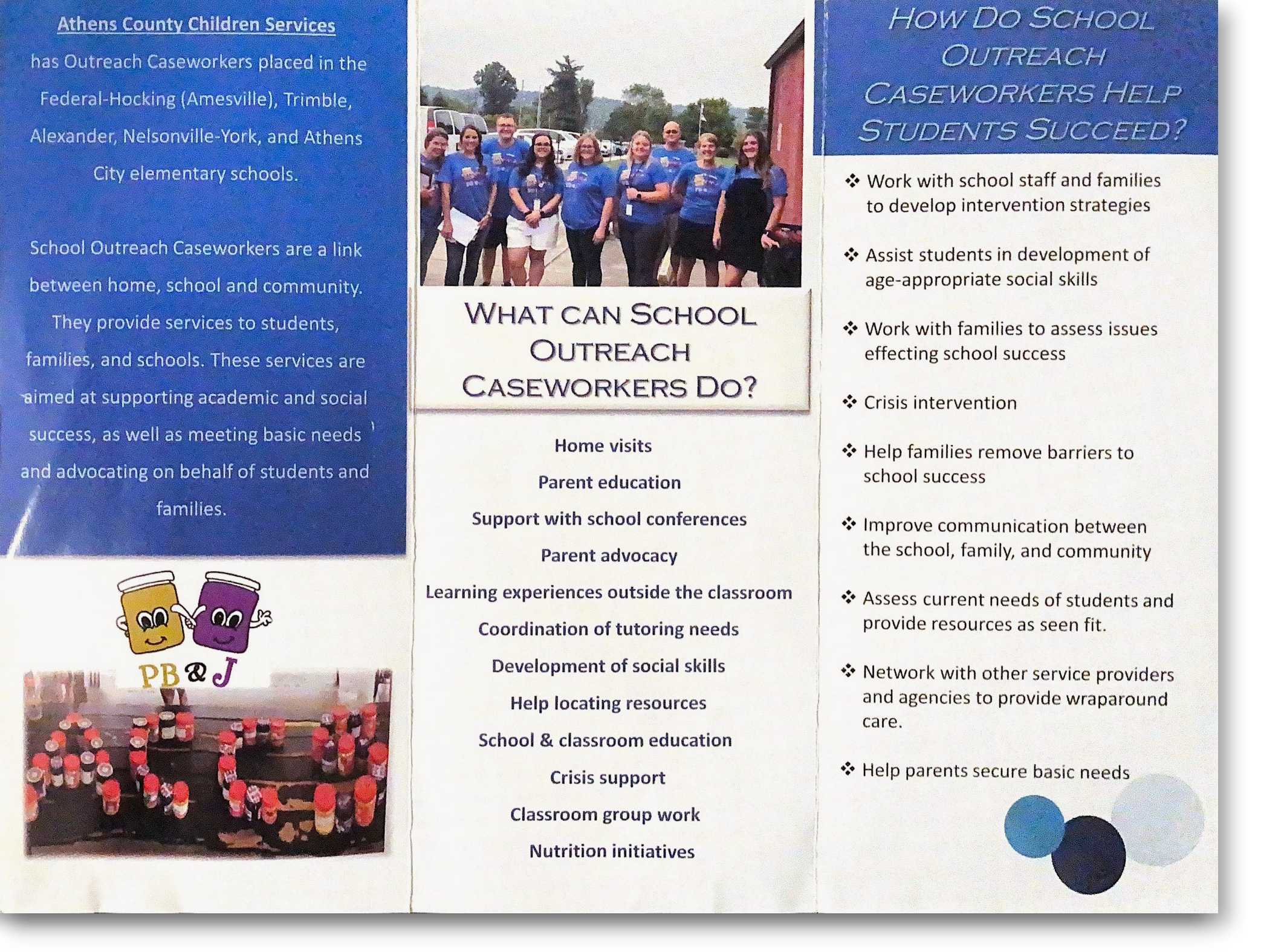

Athens County Children Services has been experimenting with a new approach to family support through its school outreach program. Rather than operate according to the traditional screening model, the program places caseworkers in local schools, where they provide aid to students and parents who request it. The idea is partly to keep families from ever reaching the point where removal is on the table.

The brochure for the Athens County Children Services’ School Outreach Program.

Jennifer Renne said courts also need to change their perspective.

“The courts focus on the maltreatment incident,” she said. “How do you know whether this incident, this injury… represents a pattern of dangerous conditions or is a one-time incident?”

“There’s two more questions, two more thresholds, that we need to cross (before we remove kids),” she explained. “One is, is the child unsafe? We can only know that when we look at the bigger picture.”

That includes looking at the nature and extent of the maltreatment, how the parent disciplines, and what their overall parenting practices are. A single incident cannot explain all that. It doesn’t indicate whether removal is the best way to address the issue.

Then there’s Renne’s second threshold: the “protective capacities of the parents.” Are parents capable of controlling the threats in the home themselves? Is there anything that could help them do so that doesn’t involve just yanking the kids out of the home?

It’s worth noting the safety assessment Ohio children services agencies are legally required to conduct before a removal includes all of this. But there’s sometimes a gap between how the law is written and how child welfare is practiced.

Bridging that gap involves moving away from the question of whether allegations of abuse, neglect or dependency are true or not, Renne said. It means developing a nuanced understanding of what the situation in a home is and how to promote stability. Often, she said, removal isn’t going to do that.

Renne also criticized the perception of many parents’ attorneys in child welfare cases, who sometimes see themselves more as facilitators of a process run by the agency rather than adversaries advocating for their clients in court.

The American court system is, by design, adversarial. It is built around opposing parties arguing with one another. That doesn’t change just because it’s juvenile court, Renne said.

However, Renne also acknowledged juvenile court upends the traditional adversarial model in a way that requires attorneys to take a nuanced approach.

“You can’t operate like a criminal defense public defender,” she said. “In other words, what do we all know a PD tells their client? ‘Don’t talk to the cops. Don’t talk to the other side.’

“If you’re representing a parent in a child welfare case and you give that advice, in the very next breath, you need to say … ‘And by the way, in 12 out of the next 19 months, if your kid’s in out-of-home care, you’re going to be facing a termination of parental rights.’”

Ohio’s statute is 12 of the past 22 months, but her point remains the same. Parents have to cooperate with agencies if they want to have any hope of getting their children back.

The Public Children Services Association of Ohio’s 2021 state report identified 1,607 children adopted and almost 3,000 more waiting for adoption. Many of these were children whose parents had their custody terminated.

Renne acknowledged this makes these cases very challenging for parents’ attorneys. Criminal defense lawyers can just fight. Lawyers in juvenile court have to pick the right moment.

But, Renne said, good attorneys pick those moments when they come along.

Working outside the court

A fierce critic like Richard Wexler may harbor very different feelings about the child welfare system than those who work in it, but they all agree on one thing: More services for families are needed if the system is going to improve.

“If (children) are in a dirty home, that’s not something that foster care is going to solve,” said Scott Britton of the Public Children Services Association of Ohio. “If they’re homeless, that’s not something that foster care is going to solve. We want that child to be safe, but those families need supports. Those families need services, not foster care.”

“The data does show that the majority of individuals that come in here fall below the poverty line,” said Zach Saunders, the Athens County judge. “And what I would say is that we need more services, we need to point them in the right direction or help them.”

Those services run the gamut from mental healthcare to welfare benefits to educational support. The more resources parents have to turn to, the less likely it is that situations in homes will deteriorate and the better off the children will be.

That does not necessarily mean pouring more money into children services agencies, however.

Vivek Sankaran, the Michigan law professor, expressed skepticism about that idea, especially if the stance toward removals doesn’t change.

“I think what that misses though is the harm to families of needless investigations,” he said. “And again, I think this is where this disconnect exists between the world we would want to create for ourselves and the one that we’re creating for other families, which is, none of us would want to be involved even in an investigation because it would cause stress, trauma, anxiety to the entire family.”

He said “fine-tuning” which cases agencies need to be involved in is more worthwhile than just expanding their reach.

Britton suggested that having more places to direct parents would help address the atrocious retention and hiring rates for caseworkers. Some counties in Ohio have more than 100% turnover in a calendar year.

Reducing the number of cases those agencies have to field might result in fewer overworked caseworkers and fewer important details falling through the cracks.

Jennifer Renne specializes in reforming the legal side of child welfare. But she recognizes the role out-of-court services need to play in the process.

“We should adopt a concurrent strategy … thinking about the multiple ways that we can handle these cases and address issues that arise in these cases in the out-of-court context,” she said. “In other words, partnering social services agencies. Setting up alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, which is a fancy way of saying, ‘Let’s get the family together. Let’s get other interested parties together. Let’s get the lawyers there, and let’s problem solve as a family and as a community.’”

Renne said she’s learned a great deal from working with American tribal communities about how to approach issues within families. “They call it peacemaking. You get everyone together. You get the community. You get the extended family. You get the parents. It’s not adversarial. We talk about what happened. We brainstorm solutions.”

“I think if state courts could adopt what we’re learning from other countries and tribal customs in terms of how to solve problems, then we wouldn’t need to go into court and have an adversarial process,” she said.

Ultimately, Renne said, everyone in a community has a stake in making sure child welfare issues are resolved justly and effectively.

“It’s also fair for us, the community, to take some ownership,” she said. “And to take some responsibility and to play a leadership role in creating a more holistic soft safety net for families to land.”