News

re: Single Moms, Living in Poverty in Ohio

By: Maren Machles

Posted on:

It’s 3:30 p.m. on Friday, and Angela is making her daughter some canned Campbell’s chicken noodle soup. Her daughter, Danielle, takes off her shoes and coat and snuggles in on the couch after a day at school. Angela heats up the stove, pours the contents of the can into a small pot and starts stirring the soup with a spoon.

The can of soup is one of a dozen or so in Angela’s kitchen cabinet – a can she bought with SNAP or Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

A year ago, Angela didn’t have a roof over her head. She had lost her mother, brother and sister unexpectedly, all in one year. They were her main support system for many years. She moved to Athens so her daughter could be closer to her father, but after falling into a deep depression, Angela was unable to support her child or herself. She checked herself into Appalachian Behavioral Healthcare Hospital.

During her time at ABH, she was unable to see her daughter, and that really took a toll on her, she said.

“That was so hard on me not to have her every day,” she said. “I struggled more then than I probably have my whole life, for that nine months that she was not under my care.”

After Angela was released from ABH, she had no one to turn to and eventually became homeless. Angela wasn’t born into poverty; she came from a middle-income family, and the transition to this new point in her life left her devastated, she said.

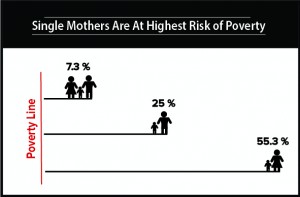

One in two single mothers, like Angela, are living in poverty in Ohio, but the Appalachian region of Ohio sees a larger rate than other parts of Ohio. In comparison, one in four single fathers are in poverty. In general, women have a harder time getting out of poverty than men, according the Ohio Poverty Report.

Most government programs are not addressing this apparent gender gap in poverty.

The Gender Gap

Ohio counties in the Appalachian region have the highest poverty rates in the state, especially after the decline of the logging and coal-mining industries. Women in the region didn’t enter the workforce until the ‘60s and ‘70s and many ended up in low-paying service industry jobs. More than four decades later, women are still struggling for wages equal to their male counterparts.

Women still make 78 cents for every dollar men which means a smaller income and less financial security. It is an issue men don’t have to face, even during times of economic change. After the decline of the coal and logging, and the loss of the high-paying jobs those industries created, men were still able to transition into jobs with similar pay, according to a study released by the Appalachian Regional Commission.

This wage gap is part of the reason for the gender gap when it comes to poverty in Appalachia, according to Rachel Terman, a professor specializing in rural sociology who teaches a class on Women in Appalachia at Ohio University.

“Women or single mothers have a harder time accessing work than do single fathers or men,” Terman said. “And even though, for example, having a full-time job where you make minimum wage isn’t enough to lift a family out of poverty, having access to full-time wages and full-time work is one of the ways of improving your chances of getting out of poverty.”

Terman also said a lack of childcare, family and friend support and a partner are reasons why many single mothers are struggling to make ends meet. She said these are all factors more accessible to men.

Women who need to provide day care for their children are usually stuck in a cycle that they can’t escape. If no one is available to watch the child and daycare outside the home is too expensive, the mother is forced to quit working. This leaves the mother stuck in unemployment and unable to provide for the child.

That is what happened to Angela.

She was working at the Hocking Valley Community Residence Center as a cook, when her babysitter quit. Without a babysitter or family support to watch Danielle at night, she had to leave her job to stay home and take care of her 11-year-old daughter. But Angela didn’t see this as dragging her down, just as another bump in the road.

“She is just an addition of me. Danielle doesn’t keep me poor. She doesn’t make it any more difficult … I would still be struggling in my life right now because of other things that led up to this point. She doesn’t hinder that in any way. If anything, she makes it a lot more tolerable.”

Angela is still struggling to find a job, but without a car or childcare, it is an uphill battle.

“That’s not the case for everyone,” Terman said. “There are definitely single mothers who are innovative and work really hard to get around the barriers that exist, but the data show us that for single mothers the social and economic barriers remain more burdensome for them than it does for men.”

Transportation

On East State Street, right next to Route 33 in Athens, is Integrated Services for Behavioral Health. A red sedan filled with papers and files and a few wrappers and water bottles is parked next to the building. That is Beth Strassman’s car.

Strassman, an integrated services counselor, spends most of her work days in her car traveling from client to client educating them on government assistance to help them get out of poverty. She works with people dealing with mental health issues or physical disabilities. Strassman is working with Angela based on her time at ABH dealing with her depression. So far, Strassman has helped Angela find a home and is currently working with her to get a job.

One of the biggest contributors to poverty is transportation. When the motor in Angela’s car blew out several months ago, she didn’t have the money to fix it. No car meant she couldn’t collect government assistance because all of the resources are spread throughout Athens County and not all are accessible with public transportation.

That is where Strassman steps in, essentially bringing the various agencies to her clients.

“It’s a lot of work, but it’s a lot of gratification in that people want the help,” Strassman said. “They want to move out of the situations that they are in. And so, a lot of times they don’t even know where they can start, and at least we can give them a path that we walk down together, rather than I lead, you follow.”

With Strassman’s help, through Integrated Services and the Ohio Benefits Bank, Angela is able to receive SNAP, cash assistance through Ohio Works First and Shelter Plus Care. Even with these benefits providing her with shelter and food, Angela still can’t start living independently and providing for Danielle, she said.

“That leaves me just broke all the time, because with what little money I do have, I have to pay bills and feed her,” Angela said. “There’s not money to go and do things. Every once in awhile we can go catch a movie, but my car has to be working for me to do that,” she laughed and shrugged. “I feel like I just can’t catch a break sometimes.”

While the benefits aren’t enough to live comfortably, Angela is grateful to Strassman for helping her get some stability, she said. Angela said she has had a lot of caseworkers who were not reliable. They wouldn’t follow through on their appointments or pick up their phones.

That was not a problem she had with Strassman. Over the course of six months, Strassman developed a relationship of trust between her and Angela.

“Building that trust is a big issue with anyone who is getting services from a complete stranger, whether you are going to the doctor for the first time or you’ve got a social worker coming to your house tomorrow. You’re going to have those butterflies in your stomach.”

What is Being Done

Not many poverty-alleviation programs target women specifically, but there is some assistance through a few government and community programs aimed at helping single parents and low-income families.

The Birth Circle, for instance, is a community of women and families devoted to supporting new families and mothers. The group started when two moms wanted to share their stories about being mothers and giving birth. Soon, they found there was a whole community of parents looking for guidance and help.

The Birth Circle offers clothing exchanges, monthly meetings and Meals for Moms, a program that helps women struggling to feed their families.

“I think something as simple as making a meal for someone can make a huge difference,” said Claudia Bashaw, executive director of the Birth Circle. “Especially if you are a single mom, you are trying to do everything to provide for your child and yourself. Having a little help here and there is really good.”

Integrated Services also offers two programs for moms, Pathways and Help Me Grow. Pathways helps single moms through pregnancy and after childbirth with the transition back to work or school. Help Me Grow is a program that goes house to house helping first time moms find the resources they need and teaching them about child development, from feeding to playtime.

WIC, or Women, Infant and Children Supplemental Nutrition Program, offers additional nutrition along with SNAP that helps at-risk mothers with malnutrition.

While there are a variety of programs available, there are no policy or political acknowledgements of this gender gap. Those providing resources in the community say one problem is outreach.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R4fsMoOZMFc

“We do the best that we can, but it would be nice if there were easier ways for us to reach out and say hey, we’re here. And we can help you. Let us do that. I think that’s a perennial struggle for a lot of groups and a lot of agencies is, how do we do better outreach?” Bashaw said.

But Angela, like many other women, doesn’t qualify for the few programs that do serve single moms because her daughter is too old. WIC, Pathways and Help Me Grow focus on moms with infants to preschool age children.

Despite all the challenges, Angela is trying hard to focus on getting out of her current situation, and then she might have the luxury of thinking about the future.

“I’ve got to do this right now because this is what I have to do to get to tomorrow or next week with my kid, but that’s not going to get us to 5 years right now,” Angela said.