News

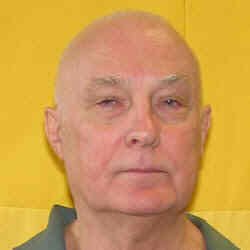

Former Sheriff Patrick Kelly Appeals Case To Ohio Supreme Court

By: Susan Tebben

Posted on:

After receiving a negative response from a higher court on appeal of his conviction, former Athens County Sheriff Pat Kelly is asking the state’s highest court to review his case.

Kelly filed a notice of appeal with the Ohio Supreme Court on Feb. 1, saying the case “raises a substantial constitutional question and is one of public or great general interest.”

The case comes for potential review by the Supreme Court after being dismissed in part by the 4th District Court of Appeals, and Kelly’s seven-year conviction upheld by the higher court.

Kelly was found guilty on Feb. 12, 2015, by an Athens County jury, of felony counts including engaging in a pattern of corrupt activity, 12 counts of theft in office, three counts of theft and one count each of perjury and failure to maintain a cashbook. The jury deliberated for 16 hours to come to the decision after listening to three weeks of arguments by Wood and prosecutors from the Ohio Attorney General’s Office.

Kelly filed notice of appeal in April of that year, citing insufficient evidence for some of his convictions, including perjury and engaging in a pattern of corrupt activity, and saying the trial court should not have found him guilty of contempt during the course of the trial.

The charges stemmed from misuse of funds from the Furtherance of Justice account and other sheriff’s office funds, along with campaign funds and profits from scrap metal sales he made during his time as the sheriff. Kelly was also found guilty of failing to keep a cashbook in the sheriff’s office.

The appeals court met in November to hear arguments on the case and filed their decision by the end of December 2016, saying the appeal to reverse the contempt finding was moot because the fine had been paid during the trial, and all other appeals were unfounded.

In his newest appeal to the Supreme Court, Kelly focuses his defense on two specific convictions.

“This case presents important and critical issues for the future of criminal defendants being charged with perjury and engaging in a pattern of corrupt activity,” Kelly states in court documents.

His argument against the corrupt activity charge revolves around the instructions given to the jury during their deliberations. Kelly writes that during the course of the trial, prosecutors spent their time asserting that two other people, Pearl “Soupy” Graham and the owner of McKee’s Auto Sales, were a part of an “enterprise” along with Kelly.

But during jury deliberation in Athens County, Visiting Judge Patricia Cosgrove was asked whether Kelly alone could represent an “enterprise.”

Cosgrove denied the request of Kelly and defense attorney Scott Wood to specify to the jury that the former sheriff could not be an enterprise on his own.

“By failing to properly respond to these questions, especially when it relates to attempting to ascertain the complicated nature of an enterprise in an organized crime criminal statute, the trial court incorrectly responded to the jury’s questions,” Kelly wrote.

Furthermore, Kelly argues, committing acts that would qualify as an enterprise involve “both interpersonal relationships and a common interest.”

Graham testified in the February 2014 trial that he used his own truck to pull a trailer of scrap metal to McKee’s, and Kelly testified that he had given Graham $50 from the proceeds of the scrap sale for gas. McKee’s was in the business of buying scrap metal and had scrapped for “a number of county agencies in Athens County and the Athens County Sheriff’s Office” in the past, Kelly argued.

“The state failed to present any evidence that (Kelly), Pearl Graham and McKee’s Auto Sales were associated together for a common purpose nor was there any evidence of ongoing organization or function as one unit,” Kelly wrote to the Supreme Court.

Graham and McKee’s were simply conducting their own affairs, Kelly wrote, with Graham merely “helping a friend and supporting a public office holder.”

Kelly further argued to the Supreme Court that a jury “may not have returned an indictment” if they knew it was Kelly who “allegedly acted alone” in the corrupt activity charge and the grand jury “may have refused to return an indictment” if they knew Kelly “allegedly used his official position and work place as the enterprise for the purpose of engaging in a pattern of corrupt activity.”

In the 4th District Court of Appeals decision, Judge William Harsha addressed the same argument that Kelly has now laid before the Ohio Supreme Court. Harsha asserted that the trial court “correctly instructed the jury that the General Assembly broadly defined ‘enterprise’ for purposes of engaging in a pattern of corrupt activity to encompass even a single individual, organization, or association,” according to the decision.

The appeals court said the trial court did not commit an error because “Kelly’s requested instruction (to the jury) was not a correct statement of law.”

The perjury charge related to a document often referred to during the trial as “list.pdf.”

Prosecutors argued that that document was not provided by Kelly as part of a subpoena for documents related to spending by Kelly as sheriff. One investigator from the Bureau of Criminal Investigation (BCI) said the document had information that was included in other documents that were provided by Kelly, but another BCI agent testified that some piece of information were different than other documents.

The perjury charge stemmed from Kelly’s statements at a pre-trial hearing in which he was asked whether any other documents regarding payments to confidential informants existed outside of those included in the subpoenaed documents. Kelly told investigators that he had used profits from the scrap sales to pay confidential informants that had since died.

A transcript included in the 4th District appeals documents shows that Kelly had stated that “to the best of my knowledge,” he had provided all the documents from the sheriff’s office regarding confidential informant payments.

Kelly was asked a second time, to which he replied “No, your Honor, not outside of what I have produced here.”

He was asked a third time by the judge at the pre-trial hearing, to ensure that other records would not “magically appear.” Kelly responded with “you will not see anything magical.”

“List.pdf” was later found on Kelly’s desktop at the sheriff’s office, and a forensic analyst from BCI said it had been created in January 2013, nine months before he testified that no other document existed that hadn’t been provided. The 4th District Court of Appeals used this information to affirm Kelly’s conviction, and said the three-judge panel reviewed the documents themselves, finding “some information that is not included in either of the other two documents provided to the state.”

Kelly stated to the Supreme Court that prosecutors never established that if his “to the best of my knowledge” statement was false, it would have affected the outcome of the trial.

“The statement made by (Kelly), if anything,w as a misstatement that could in no way hold an intention to mislead or to hamper any investigation, as the document at issue and which was on (Kelly’s) computer held the exact same information that was contained on the documents that were turned over to the state,” Kelly wrote.

Kelly is currently housed in the Allen-Oakwood Correctional Institution in Lima.

Along with his notice of appeal, Kelly filed an affidavit of indigency, a document which asks the court to waive filing fees due to the inability to pay.

In the affidavit, Kelly wrote that he receives $18 in monthly income from working within the prison.

Kelly is being held in “protective” custody at the prison, according to a spokesperson for the prison. This is typically done for members of law enforcement who enter prison.

A spokesperson for the Ohio Attorney General’s Office said the office had no comment on the notice of appeal, and is awaiting the Supreme Court’s decision on whether to see the case.