News

Growing Hazards: Safety Rules Often Don’t Apply To Farming…

By: Nicole Erwin | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

One of the Most Dangerous Jobs

Jeanna Glisson has two lives: her life before August 20th, 2007, and her life after. That day is so vivid, Glisson can still hear the sounds of her son’s feet coming down the stairs.

“I remember Derek when he got up that morning, he was on the phone talking to my dad. He was excited,” Glisson said.

It was the first day of harvest at Swift Farms in Murray, Kentucky, and Derek couldn’t wait to get to the corn fields. Glisson remembers it feeling like the hottest day of the year. It was a Monday, she said.

“He looked forward to it. I remember him getting in the shower. And then after that…” Her voice trails off. She remembers that the phone rang. It was her brother. Derek had been hurt. Before Glisson or any of the emergency responders could get to the farm, it was too late.

“He was dead on arrival,” she said.

Just hours before, Derek, his grandfather, and a couple other farm workers had been trying to reattach a piece of equipment to a combine. They had gone through the motions to make sure the part was attached, even lifting the piece three times before Derek crawled under the machine. But somehow, the equipment slipped.

“It was a tragic, tragic accident is the best way I can explain it. I don’t think there was one thing they could have done differently,” Glisson said.

On her way through the flashing emergency lights and long line of neighbors along Faxon Road, Glisson finally made it to her son. “He looked peaceful, like he was asleep,” she said.

The Calloway County Coroner said Derek died from mechanical asphyxia from crushing injuries.

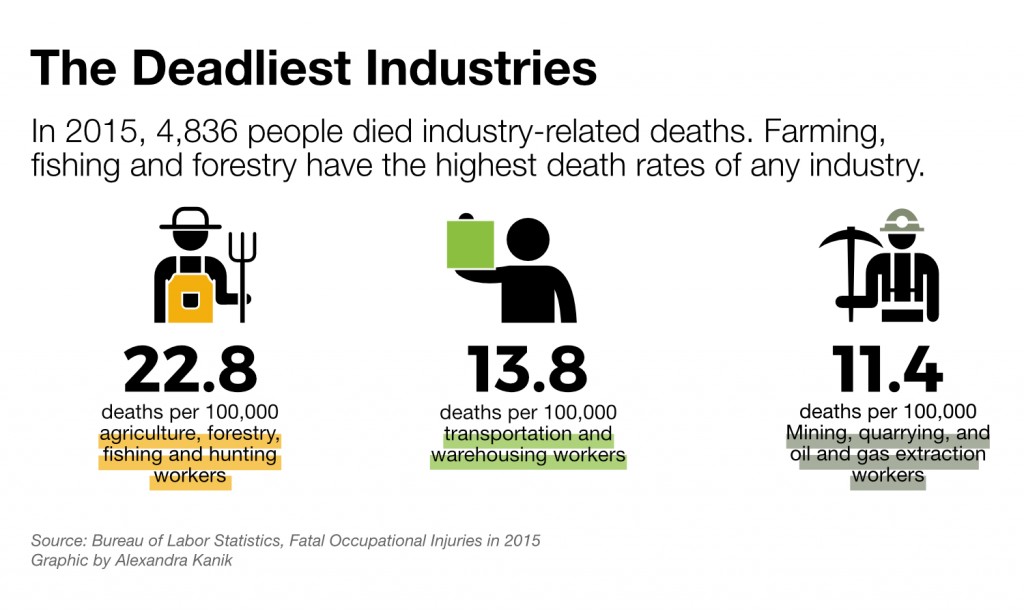

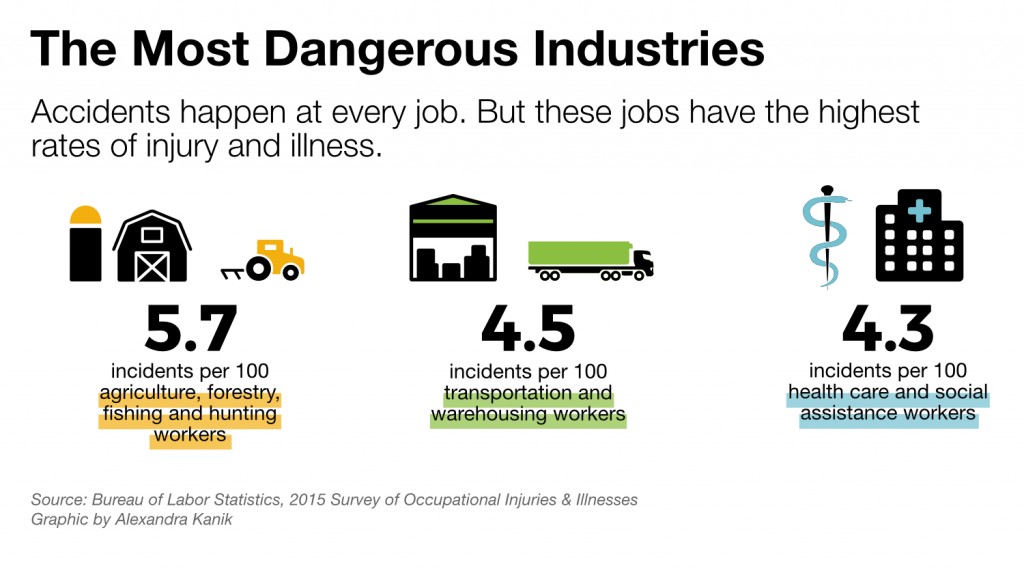

Farming is among the country’s most dangerous occupations. Government statistics show the industry consistently has some of the highest risks for injury and death from work-related accidents, and the Ohio Valley region is no exception.

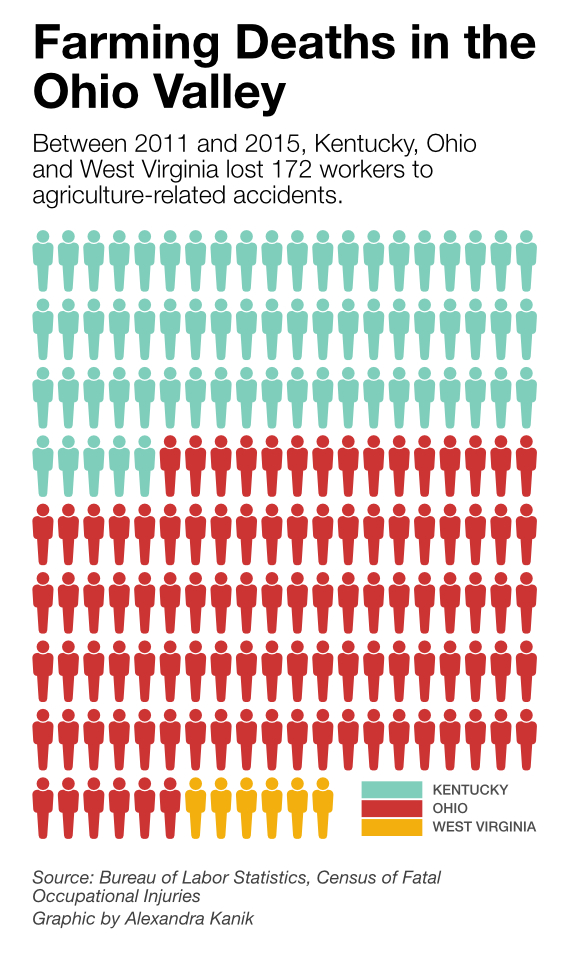

A ReSource review of data on agriculture-related deaths shows that from 2011 to 2015, Ohio had 101 fatalities, the fifth highest such number in the nation. Kentucky had 65 fatalities over those five years, the 14th highest in the nation. West Virginia, which has relatively few people in farming, had six fatalities.

Agribusiness leaders say voluntary training and awareness are improving safety. But veteran safety regulators say enforcement is also lacking. Unlike with other industries, safety regulators are restricted on what they can do to help when it comes to injuries and fatalities on the farm.

Farm Loophole

Jordan Barab is a former deputy assistant secretary of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, or OSHA, who has been blogging on worker safety issues since leaving government at the end of the Obama administration. Barab said the agency faces frustrating limitations when it comes to farms, especially small farms, which statistics show are generally more hazardous.

“Basically, OSHA is not allowed to go on any small farm,” he said. “And that means for any reason.”

“Small” is defined as having fewer than 11 workers other than family members and no migrant labor housed on the farm.

Barab said this loophole in worker safety for small farms exists because of the political sway of agriculture lobbyists, including the Farm Bureau.

“If there is a worker complaint, if a worker gets killed, if ten workers get killed, OSHA can’t even step foot on there to cite or anything,” he said.

A lot of people get hurt and killed on farms and Barab said it’s because of the nature of the work environment. Risky activity, confined spaces such as grain silos, and dangerous, heavy machines are all areas where he thinks inspectors could be helpful.

“There are all kinds of issues on farms that OSHA could address,” he said.

During Barab’s time at OSHA, he said, the department was often stopped in its tracks if it came close to issues regarding agriculture. In Barab’s blog “Confined Space” he wrote that agribusiness lobbyists accused his agency of “destroying the great American family farm” when it attempted what he considered common sense safety improvements:

When OSHA tried to protect workers — not through regulations, but through clarifications or new enforcement initiatives for existing regulations…when we were trying to save the lives of workers — often teen-age kids — from suffocating in grain silos, when we tried to correct a misinterpretation of OSHA’s Process Safety Standard to compel small fertilizer establishments (like West fertilizer that exploded in 2013, killing 15 people and leveling part of the town) to take basic precautions with hazardous materials that other chemical establishments were required to take.

Barab said OSHA offers more than just enforcement. Consultation services in every state allow for inspections to improve practices without penalty.

“There will always be employers who want to cut corners” said Barab, and that’s who needs enforcement.

Even getting accurate numbers on farming injuries and deaths can be frustrating. A study by the Ohio Commission on the Prevention of Injury found that “there is a gap in the fatality and injury reporting systems for the agricultural occupation.” With at least ten different sources of data on work-related safety incidents, “the United States does not have a unified reporting system.”

Farm Bureau spokesperson Paul Schlegal said bureau policies are decided by delegates from all fifty states at annual meetings. He said their consensus is that safety awareness works best through grassroots training efforts with local programs.

“I don’t think OSHA was set up to regulate safety on small farms,” he said. “And you have seen for literally decades a Congressional directive that supports that point of view, so I don’t think that is going to change.”

“Safety begins with each individual employer,” Schlegal said, and responsibility to follow safe working rules and conditions falls on the employees.

Future Farmers

Future Farmers of America provides some of this training. In the Ohio Valley the FFA has chapters with more than 45,000 students.

Kentucky FFA Executive Secretary Matt Chaliff said farm safety “seems to have renewed interest.” Just this year national FFA is moving to include safety as one of its “15 areas of interest” to drive safety awareness to all its member chapters. A new agreement with Safety in Agriculture for Youth will also provide online resources.

Chaliff said instilling safety awareness into behavioral practices is different when it comes to younger farmers who often exhibit what he calls an “invincibility” attitude. They tend to overestimate their abilities and underestimate risk. Add a four-wheel All Terrain Vehicle, or ATV, into the mix, and those risks increase significantly, he said

“We see a huge issue with ATV’s,” he said, noting the many injuries resulting from their use. “ATVs have become such a prevalent part in agriculture. It’s something we need to get a handle on.”

Life Lessons

Farmer and college student Brandon Pepper attended FFA classes before he graduated from LaRue County High School in Hodgenville, Kentucky. Last year, Pepper had a freak accident on the farm that he said resonated more than the FFA seminars ever could.

“My father and a couple of hired hands were working on a piece of tillage equipment out in the field,” Pepper said. His family repurposes old farm equipment as a small side business.

“We had a guy hitting metal with a hammer, and my father was running the torch, and I was running the bottle-jack, and putting a lot of pressure on this piece of metal that we were trying to move,” he said. “All of the sudden it moved very fast.”

Pepper said he didn’t realize what had happened until he looked down at his hand.

“My thumb,” he said, “was hanging by a little bitty piece of skin, I could have cut it off with a pair of fingernail clippers.” The thumb was spared, but the knuckle was not.

But even after nearly losing his thumb, Pepper still resists regulations. If he could turn back the clock and bring an agency like OSHA on the farm, he said, he wouldn’t.

“It makes things more difficult to do,” he said.

Pepper’s comments reflect a deep mindset in farming country, one that prizes independence and self-reliance and resents government intrusion. However, he is open to other ways of improving safety practices.

“If there was some kind of nonprofit organization that wasn’t going to come in and tell us what we could and could not do and just try and help us,” he said. “I feel like that could be beneficial.”

Putting Safety In Neutral

That is where organizations such as Ag Safe, a nonprofit farm training organization, can step in. Ag Safe started in California in 1991. This year Development Director Natalie Gupton opened an office in Kentucky.

“In our 26 years of existence we have yet to meet a farmer that wants something bad to happen to their workers,” Gupton said.

Gupton said Ag Safe offers a “neutral third party” for farmers who need better safety training and awareness and help managing the regulations they face. She expects the organization will likely expand to include Ohio and West Virginia as well. From proper pesticide use to updated farm equipment, she said, a myriad of compliance concerns that come with at least eight government organizations can overwhelm farmers.

“There’s so many organizations that a farmer has to deal with, big or small, when they’re working with our nation’s food supply,” Gupton said.

Gupton said she doesn’t think additional regulation is the right approach. She said communication often isn’t good among different government departments. That means rules can overlap and farmers can be confused on whether allowing one regulator on their fields could create a conflict with another agency limiting who can be among crops.

Because Ag Safe isn’t a regulator, farmers and insurance companies seem to welcome its presence.

“We’ve had stories from past clients that an issue happened on their farm but because they were involved with AG Safe the liability was waived. Because they had taken the measures and had established protocols and procedures in place, they were not found at fault,” Gupton said.

In some parts of farming country, insurance companies offer incentives for safety training. North Dakota, for instance, encourages farmers to enroll in specific training programs with a discount of up to 25 percent on annual premiums. No such incentives are available in the Ohio Valley.

Painful Reminders

Whether the solution lies in more voluntary programs, more enforcement efforts, or some combination, the numbers on farming’s risks indicate that more should be done to make farms safer for families and workers.

Jeanna Glisson lives with painful reminders of the lives those numbers represent. This summer marks the tenth anniversary of Derek’s death at age 21.

“We used to live in a world where you think bad things don’t happen,” she said. “And now we’re like, ‘bad things could be right around the corner at any given moment.’ So we try to stay more aware, we try to be more safety conscious, I believe.”

Glisson has her own incentive plan for bringing awareness to young farmers. This August, she is organizing a tractor pull to raise awareness about the dangers of farming through a scholarship in Derek’s memory.