News

Without A Net: Rural Residents Band Together For Internet Service

By: Benny Becker | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

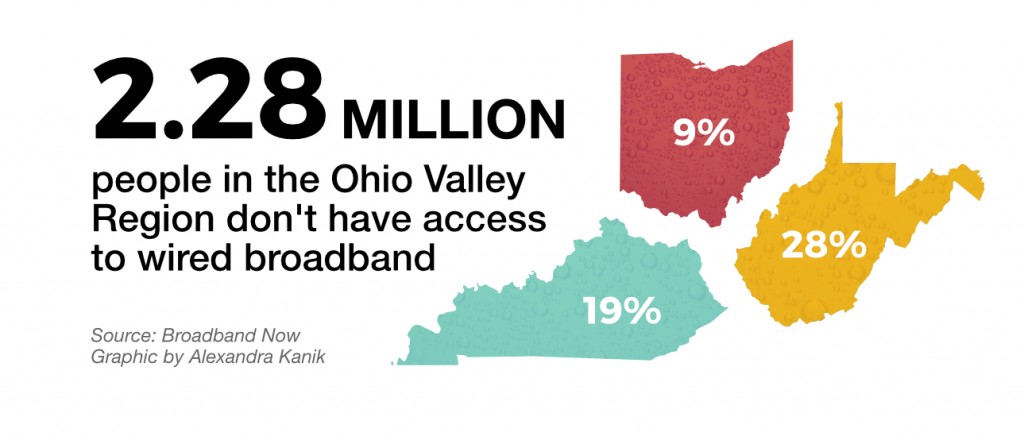

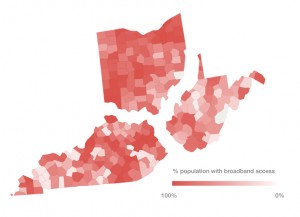

Nearly half of the people living in rural parts of United States don’t have access to broadband internet, the high speed connection required for common uses many of us take for granted. Government and survey data show that in 65 counties across Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia, the majority of residents don’t have access to broadband–that’s one-quarter of all the counties in the three states.

With the internet continuing to grow in importance for school, work, and for everyday life, many disconnected rural communities see their lack of internet access as an existential threat. Some communities hope that by banding together, communities can find ways to bring fast internet to places it’s never been.

Offline in Linefork

Jamelia Lewis lives in little valley tucked away in the mountains of Letcher County, Kentucky, in a rural area called Linefork. It’s a place with a strong sense of heritage.

Lewis lives in the house where she grew up, a former schoolhouse that her grandfather built. She’s chosen to stay home in order to help take care of her parents. Lewis has a background in accounting, but she’s had a hard time finding a work-from-home job, which would allow her to continue to take care of her elderly parents.

“I was actually offered a job where I could work from home but I couldn’t take the job because there’s no internet,” she said.

Rural residents worry that poor internet service will hold back their youth. (Malcom Wilson)

The lack of connectivity has also made homework a challenge for Lewis’ children, especially for her younger son who’s visually impaired. The school has loaned him an iPad that he can use to zoom in on the text in his assignments, but without broadband connection he can’t send and receive assignments from home.

“I feel like he’s getting left behind because he doesn’t have what he needs to get his education,” Lewis said, “and that’s not fair.”

“Our Heritage Will Die”

Tina Sparkman lives nearby on a farm that’s been in the family for generations. Her family’s only choice is satellite internet, which isn’t very reliable. Sparkman said that on a good day, it takes ten minutes to load a three minute video on Facebook.

“And if the wind’s blowing, the satellite isn’t working,” she said with a laugh.

Sparkman has a son attending Eastern Kentucky University. He can’t trust that the family’s internet will let him do his homework, so he stays on campus, which costs the family more money, and means they don’t get to spend as much time together.

Tina Sparkman worries more about what will happen after her son finishes college. “My children won’t come back here to live if things don’t change,” she said. “Our heritage will die here with my generation.”

KentuckyWired

Kentucky state officials have been pushing to expand broadband access for years. Eastern Kentucky, long known for coal mining, is represented by Congressman Hal Rogers who hopes the internet can help the area rebrand itself.

“In talking about our future, I have half-facetiously referred to our area as ‘Silicon Holler,’” he said.

Rogers has worked with two Kentucky governors on a project called KentuckyWired, which would build a fiber-optic network across the entire state. The plan for the first phase is to start from a connection to the backbone of the internet in Cincinnati, and then build three loops— first to Lexington and Louisville, than two more loops to cover areas due south and east.

The eastern Kentucky section was originally scheduled to go online in 2016 but there have been significant delays. The state is just starting to install small buried segments of fiber-optic cable. There’s still more work to be done before the state will have all the rights and plans it needs to hang cable on utility poles.

And for residents waiting on KentuckyWired to bring them internet connection, there’s one more catch: The network won’t connect directly to anyone’s home. The project is building the so-called “middle mile,” but it’s up to internet providers and local communities to build the “final mile” that connects to homes and businesses.

Letcher County and four of its neighboring countiess have teamed up and hired consultants to make a final mile plan. One of the consultants, Eric Mills, told the group they should expect a cost of $40,000 a mile when installing a fiber-optic network. “It’s expensive but it’s essential,” Mills said. “We’ve got to give ourselves a swift kick in the rear to make sure we compete.”

Letcher County seems to have taken that message to heart. The county government created a broadband board, made up of volunteers from the community. When the board came to Linefork in February, Jamelia Lewis, Tina Sparkman, and dozens of their neighbors came out to hear about the plans for a better internet connection. Harry Collins, who chairs the broadband board, told the crowd that the board was applying for a $1.5 million dollar federal grant to install broadband internet in Linefork.

West Virginia Takes Notice

In West Virginia, a recent law builds on some of the lessons learned in Kentucky. The measure was introduced by Delegate Roger Hanshaw, who represents Clay, Calhoun, and Gilmer Counties. “A three-county district without a stoplight,” Hanshaw described it.

Henshaw has firsthand experience with the challenges of life without broadband at the small hardware store his family owns.

“There are days when we have trouble processing a credit card sale,” he said.

One part of the new law aims to prevent delays like those KentuckyWired has faced when trying to get access to utility poles. Another section encourages West Virginia communities to band together so that, like the Letcher County Broadband Board, they can apply for federal money.

Hanshaw said that West Virginia has failed to take advantage of that funding for the past several years, likely because the law didn’t explicitly allow for communities to form internet co-ops.

The law passed the West Virginia legislature with ease.

“There’s just no excuse for service being so poor that we can’t process a credit card sale,” Hanshaw said. “I think that message has been communicated very clearly to all 134 members of our legislature by their constituents.”

Hopeful Signals

It may still be years before these communities get access to broadband internet. But in places like Linefork where people are coming together, hope is within reach.

And that’s what Jamelia Lewis is holding onto. “I’m just hoping my little boy can do his homework.”