News

CHARTS: Here’s How GOP’s Tax Breaks Would Shift Money To Rich, Poor Americans

By: Danielle Kurtzleben | NPR

Posted on:

So, $1.4 trillion is a lot of money. It’s what all of the NFL teams together are worth, and then some. It’s more than twice the Defense Department’s 2016 budget. It’s enough to buy nearly 3.2 million homes at the median U.S. home price right now.

It’s also roughly the amount that the proposed Republican tax overhaul would add to the deficit over 10 years — not even counting interest.

So in the House and Senate tax bills, where does all that money go? A big chunk would go to businesses, as both chambers want to drastically cut corporate tax rates. The rest, on the individual income tax side, will benefit many — but by no means all — in the middle class, and altogether, it will by far benefit the richest Americans more, according to recent estimates. Meanwhile, the majority of the poorest Americans would see little change in their tax bills.

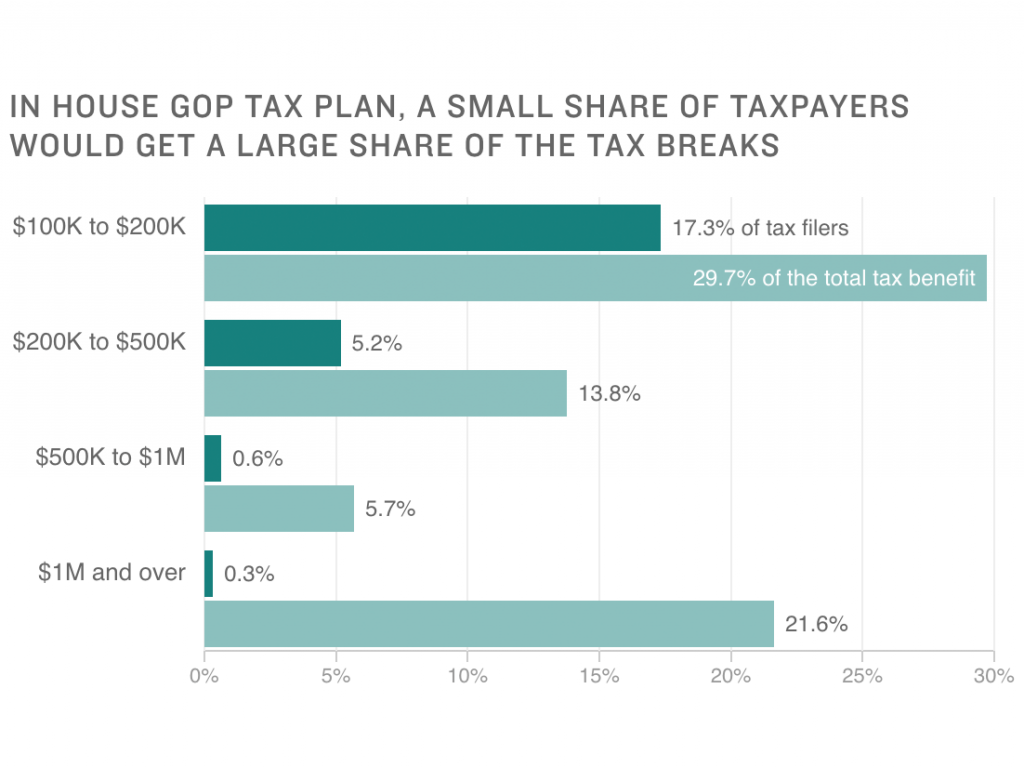

Altogether, under the House bill, around 70 percent of the tax benefits would initially flow to people earning six figures or more per year (or about 23 percent of tax filers), according to an NPR analysis of figures from the nonpartisan congressional Joint Committee on Taxation. Here’s a look at the House and Senate numbers alike.

How the initial numbers look

Under the initial House GOP tax plan, the majority of the very poorest Americans would have very little change in their tax bills each year. That is true in the near term (for tax year 2019) and the long term (2027) alike, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation.

In 2019, the majority of tax filers making $30,000 and more would have a sizable cut in their taxes. That would diminish over time. In 2027, it’s only in the groups of people making $50,000 or more that the majority of taxpayers would see a decline in their taxes under the House bill.

So it’s true that there are a good number of middle-class Americans who will get an at least moderately smaller tax bill — more than 40 percent of taxpayers making between $50,000 and $100,000 would see tax decreases of more than $500 in 2027.

But it’s also true that a bill being sold as a “middle-class” tax plan could increase taxes for a sizable chunk of middle- and lower-income Americans — for a few middle-class income groups, around one-fifth would see a tax hike as of 2027 under the House bill. And it’s also true that a majority of the lowest-income Americans would see little change at all in their tax bills.

In the Senate bill, fewer middle-class homes would potentially see a tax hike, but the homes most likely to see a sizable tax cut would still be the richest.

Gamed out another way, here’s how it would look: As of 2019, under the House bill, tax filers making less than $50,000 will account for around half of all filers. They would also receive around 8.2 percent of the total change in federal taxes, according to the JCT’s initial calculations of the House bill.

The nonpartisan Tax Policy Center has likewise estimated that the highest-income Americans would gain far more than lower-income Americans under the House plan.

On the Senate side, money is still disproportionately shifted to richer people, but not quite as drastically as in the House bill.

Benefits for poor Americans don’t change much

The numbers thus far show that a majority of low-earning Americans would see little change in their tax bills.

But then, many people in that group pay zero taxes or negative-income taxes, in other words, many get a check from the government. The programs that do a big part of that wouldn’t change much under this bill. A couple of tax credits in particular help working-class Americans the most.

“Basically for working-class people, the things in the tax code that matter most to them are the [Earned Income Tax Credit] and the child tax credit, and if you look at [the House] bill, the EITC is just nowhere. They don’t do anything to it,” said Chuck Marr, director of federal tax policy at the left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Senate Republicans have likewise given no indication that they will be changing the EITC.

To explain: The EITC, a tax credit available to the lowest-income Americans, is one of the biggest poverty-fighting measures in the U.S. Like any other tax credit, it subtracts a certain amount directly from a taxpayer’s tax bill.

But on top of that, it’s what is known as a “refundable” credit — that is, even if a taxpayer owes zero in income taxes, they can still get the tax credit paid out to them.

On top of that, there is the child tax credit. That credit is partially refundable, and the portion that is refundable would only rise slowly under either version of the bill.

The argument to boost the poorest Americans through the tax code isn’t just one that left-leaning experts are making, either. Economist Michael Strain, from the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute, also has argued that the House bill should “do more to fight poverty and advance opportunity” and called on Congress members to increase the EITC.

He pointed out that the idea has bipartisan support, having been promoted by both former President Barack Obama and current House Speaker Paul Ryan, R-Wis. For his part, Ryan has been selling the tax cut using other numbers — he and other House Republicans argue that the plan will give a “typical family” of four earning $59,000 per year a $1,182 annual tax cut. PolitiFact declared that claim “half true.”

A big boost for businesses

Altogether, $1 trillion of the $1.5 trillion cost of the House bill would go toward business, according to an initial analysis from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget — $2.2 trillion in cuts, minus $1.2 trillion in business tax increases. Meanwhile, around $300 billion will go to individuals: $3.3 trillion in tax cuts for individuals, minus $3 trillion in tax increases.

To be clear, that’s not all about megacorporations and includes tax changes for smaller businesses.

And while it’s not money that goes directly to American workers, cutting taxes for American businesses has been a big part of Republicans’ push for tax overhaul.

“I think there are a collection of provisions [in the House bill] — corporate, territorial, expensing, the 25 percent pass-through rate — that, taken as a whole, are very much a set of greatly improved incentives for firms to invest, innovate [and] hire people and pay them in the U.S.,” said Doug Holtz-Eakin, director of the Congressional Budget Office under President George W. Bush and president of the right-leaning American Action Forum.

And that’s why Republicans talk a lot about “growth effects” when they’re selling the tax plan — the idea that the economic growth spurred by lowering taxes will create positive knock-on effects, meaning higher incomes and employment.

When economists do what is called “dynamic scoring,” they take this into account. The right-leaning Tax Foundation found that without growth effects, the House plan would be better for higher-income than lower-income Americans. That’s roughly in line with what the Joint Committee on Taxation and the Tax Policy Center found.

But with dynamic scoring, the Tax Foundation found the effects for some lower- and middle-income people would be bigger than those for the richest.

This kind of thinking is a big part of how the White House markets corporate tax cuts. The Trump White House has argued that the cuts to corporate taxes would benefit American workers by thousands of dollars per year, as businesses bring money back from overseas, pass savings on to workers and boost hiring.

Many economists, including those on the right, believe the White House’s projections were far too rosy. But they agree that the principle is right: Corporate tax cuts could easily benefit workers.

“The goal collectively is to raise productivity growth,” Holtz-Eakin continued. “So we’ve had terrible productivity growth. It’s one reason we’ve seen things stagnate.”

Importantly, none of the numbers here are final. The Senate will be making amendments to its bill soon, and then, both chambers would then have to conference to compromise on their two tax overhauls.

9(MDI4ODU1ODA1MDE0ODA3MTMyMDY2MTJiNQ000))