Communiqué

AMERICAN EXPERIENCE The Secret of Tuxedo Park Premieres Tuesday, January 16

< < Back toAMERICAN EXPERIENCE The Secret of Tuxedo Park

Premieres Tuesday, January 16, 2018 on PBS

The Story of the Mysterious Tycoon Turned Scientist Who Helped

Win World War II

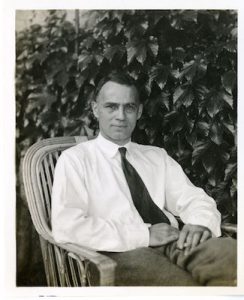

In the fall of 1940 the fate of Western civilization hung in the balance. Hitler’s armies were encamped along the English Channel, preparing for an invasion of Britain. In a desperate bid to form a technological alliance with the then-neutral United States, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill sent a small team of scientists on a clandestine transatlantic mission to deliver his country’s most valuable military secrets to America’s scientific leaders. When Churchill’s emissaries arrived, they delivered the most precious item in their collection — a revolutionary radar component — to a mysterious Wall Street tycoon, Alfred Lee Loomis. Loomis had for years led a double life, spending his days earning vast fortunes on Wall Street and his weekends working with the world’s leading scientists at his private laboratory in Tuxedo Park, outside New York City. Using his connections, his money, and his brilliant scientific mind, Loomis assembled a team of the brightest scientists, and directed their efforts such that radar would arguably play a more decisive role than any other weapon in the war. Based on Tuxedo Park: A Wall Street Tycoon and the Secret Palace of Science that Changed the Course of WWII by Jennet Conant, The Secret of Tuxedo Park reveals the long-overlooked story of an extraordinary yet unheralded man. Written and directed by Rob Rapley and executive produced by Mark Samels, The Secret of Tuxedo Park premieres on AMERICAN EXPERIENCE on Tuesday, January 16, 9:00-10:00 p.m. on PBS.

“To think that this unknown man, toiling in a secret lab, with some of the greatest scientific minds of the era, made such a profound impact on the outcome of the Second World War is remarkable,” said Mark Samels, AMERICAN EXPERIENCE executive producer. “These little-known but fascinating stories add new dimension to our understanding of history.”

“To think that this unknown man, toiling in a secret lab, with some of the greatest scientific minds of the era, made such a profound impact on the outcome of the Second World War is remarkable,” said Mark Samels, AMERICAN EXPERIENCE executive producer. “These little-known but fascinating stories add new dimension to our understanding of history.”

Alfred Loomis didn’t start out reclusive, a millionaire, or even a scientist. After graduating from Harvard in 1912, he became a corporate lawyer on Wall Street, married well, and settled in the upscale suburb of Tuxedo Park, outside New York City. But under his conventional façade was a man of fierce ambition, obsessed with scientific exploration. With the outbreak of World War I, Loomis got a reprieve from the humdrum world of finance; he was posted to the Army’s research center in Maryland, where he got his first intoxicating taste of science on a large scale.

Following the war, Loomis’s plan was to amass enough of a fortune to pursue science full-time. Even as he was conquering Wall Street, Loomis kept up with the scientists he had met during the war, including physicist Robert Wood. Loomis enlisted Wood, and the two men began exploring the effects of high frequency waves using a massive GE oscillator they installed in his mansion’s garage. Quickly outgrowing his makeshift lab, Loomis purchased nearby Tower House, an enormous crumbling Gothic mansion, and turned it into a state-of-the-art laboratory. The fiercely private Loomis shunned publicity but the comings-and-goings of foreign scientists gave rise to rumors and speculation about what was transpiring at his mysterious lab.

In the spring of 1933, Loomis was finally wealthy enough to walk away from Wall Street, and devote himself entirely to research at Tower House. Loomis pioneered ultrasound technology, became a leading authority in precise measurements of time, and, using his son as a subject, became one of the first to measure and describe the stages of sleep. As author Jennet Conant says of Tower House, “It’s beyond a scientific playground. This is a scientific idyll. There is nothing like it anywhere in the world. Einstein refers to Loomis’s compound as a ‘palace of science’ and it truly is.”

As the 1930s drew to a close, the rumblings from Europe became increasingly dire. Most Americans wanted nothing to do with another European war, but Loomis saw it differently. He had seen Hitler’s Germany with his own eyes, and had helped scientists — many of them Jews — escape the Nazis. With Europe still at peace, Loomis dedicated himself to what must have seemed a forlorn hope: he would find a way to counter Germany’s technological edge. Loomis soon focused all his energies on the next generation of a vital new technology: microwave radar.

As the 1930s drew to a close, the rumblings from Europe became increasingly dire. Most Americans wanted nothing to do with another European war, but Loomis saw it differently. He had seen Hitler’s Germany with his own eyes, and had helped scientists — many of them Jews — escape the Nazis. With Europe still at peace, Loomis dedicated himself to what must have seemed a forlorn hope: he would find a way to counter Germany’s technological edge. Loomis soon focused all his energies on the next generation of a vital new technology: microwave radar.

When the Germans invaded France in early 1940, President Roosevelt created a small but powerful organization to develop the sophisticated new weapons that would be needed in a war with Nazi Germany; Loomis was put in charge of the microwave radar section. But even with the resources of the federal government, Loomis’s program slowly ground to a halt. Nobody knew how to build one vital component that would make microwave radar a reality. As Loomis was about to give up, Churchill decided to make one of the biggest gambles of the war. British scientists had been making headway on the radar problem, but they lacked the resources to continue. In a daring move, Churchill handed the Americans his country’s most precious military secrets — jet engines, anti-submarine devices, explosives and, most importantly, a new type of radio tube called the cavity magnetron — the very thing Loomis’s microwave radar team needed.

Several companies were interested in getting their hands on the burgeoning new program but Loomis instead created a new type of research operation at the intersection of industry, the military, and academia — what became known as the “Rad Lab’ at MIT. Thanks to Loomis and his team of nearly 4,000 people, the U.S. would go to war in December 1941 with a radar program as advanced as any in the world. The breadth of the Rad Lab’s innovation was on full display during the invasion of Normandy, when airplanes equipped with radar sets bombarded the coastline, radar beacons guided parachute troops, a navigation system known as landing craft control directed the invasion forces and radar-directed guns protected the infantry from air attack. After the Japanese surrender, when their story could finally be told, the radar men could justly claim “the Bomb only ended the war, radar won it.”

The Rad Lab closed its doors at the end of 1945. When Loomis died in 1975, his passing attracted little attention. He wouldn’t have wanted it any other way.

The Rad Lab closed its doors at the end of 1945. When Loomis died in 1975, his passing attracted little attention. He wouldn’t have wanted it any other way.

About the Participants, in Alphabetical Order

Robert Buderi is the founder, CEO, and editor in chief of XConomy and one of the foremost journalists covering business and technology. Before taking his most recent position as a research fellow in MIT’s Center for International Studies, Buderi served as Editor in Chief of MIT’s Technology Review. He is the author of four books about technology and innovation including The Invention That Changed the World (1996).

Jennet Conant is the author of four bestsellers including Tuxedo Park: A Wall Street Tycoon and the Secret Palace of Science that Changed the Course of WWII.

Michael Hiltzik is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who writes the daily blog “The Economy Hub” for The Los Angeles Times.

Jackie Quillen is Alfred Loomis’s granddaughter.

Jacqueline Loomis is Alfred Loomis’s daughter-in-law.

Mary Loomis is Alfred Loomis’s granddaughter.

David Zimmerman is a professor of history at the University of Victoria and author of Top Secret Exchange: The Tizard Mission and the Scientific War and Britain’s Shield: Radar and the Defeat of the Luftwaffe.