Communiqué

AMERICAN EXPERIENCE “The Gilded Age” Premieres Tuesday, February 6

< < Back toNew Documentary Explores the Tumultuous Era That Set the Stage for Modern America

Thirty years after the Civil War, America had transformed itself into an economic powerhouse and was fast becoming the world’s leading producer of food, coal, oil and steel. But the transformation had created stark new divides in wealth, class and opportunity. By the end of the 19th century, the richest 4,000 families in the country — less than one percent of all Americans — possessed nearly as much wealth as the other 11.6 million families combined. The simultaneous growth of a lavish new elite and a struggling working class sparked passionate and violent debate over questions still being asked today: How is wealth best distributed, and by what process? Should the government concern itself with economic growth or economic justice? Are we two nations — one for the rich and one for the poor — or one nation where everyone has a chance to succeed? A compelling portrait of an era of glittering wealth contrasted with extreme poverty, “The Gilded Age” is produced and directed by Sarah Colt and executive produced by Mark Samels. The film premieres on AMERICAN EXPERIENCE on Tuesday, February 6, 2018, 9:00-11:00 p.m. on WOUB.

“We often hear pundits say we’re living in a second Gilded Age,” said Mark Samels, AMERICAN EXPERIENCE executive producer. “Once again, people are questioning whether America is fulfilling its promise, if there really is equal opportunity for everyone. Examining the original Gilded Age reminds us that the questions and debates we currently wrestle with are ones that have defined us for over a century.”

“We often hear pundits say we’re living in a second Gilded Age,” said Mark Samels, AMERICAN EXPERIENCE executive producer. “Once again, people are questioning whether America is fulfilling its promise, if there really is equal opportunity for everyone. Examining the original Gilded Age reminds us that the questions and debates we currently wrestle with are ones that have defined us for over a century.”

The Gilded Age, as it later came to be known, was dominated by larger-than-life men who wielded power across industrial and economic sectors. Andrew Carnegie, whose steel empire made him one of the richest men in history, grappled to make sense of his meteoric rise to wealth. Tycoon J.P. Morgan established himself as a financier more powerful than the president and consequently was able to save the government itself from bankruptcy. The fortunes these men accumulated enabled lives of unparalleled opulence. They built massive mansions and museums, country estates and yachts. Society mavens, like Alva Vanderbilt, who married the grandson of railroad baron Cornelius Vanderbilt, threw extravagant and exclusive parties and courted the press to secure their family’s status as members of a new American aristocracy.

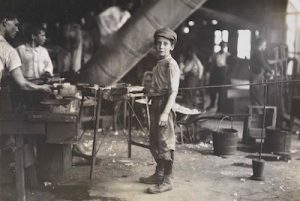

As the elite luxuriated in splendor, America’s cities were bursting with immigrants and former slaves looking for opportunity. New York became the nation’s first metropolis with a million inhabitants, nearly doubling its population in a generation. Jobs were abundant, but employers often expected everyone — including children — to work 12-hour days, six days a week. Henry George captured the imagination of the working class with his best-selling Progress & Poverty, which condemned the growing economic inequality and put forth the premise that poverty was not due to personal failure but caused by a rigged system. George saw New York as a city in which “on one side a very few men richer by far than is good for men to be, and on the other side a great mass of men and women struggling and worrying and wearying to get a most pitiful living.” His popularity led to a nomination as the Labor candidate for mayor of New York. Despite his narrow defeat, George’s message resonated: Was America a land of opportunity or a closed system run by the few for their own gain?

A growing discontent among working people was not confined to the nation’s cities. Farmers in the Midwest — whose wheat, corn, oats and rye fed the world — were working dawn until dusk for meager returns. In Kansas, Mary Elizabeth Lease, a firebrand and feminist, criss-crossed Kansas advocating for farmers’ rights. “It is no longer a government of the people, by the people, and for the people,” she proclaimed, “but a government of Wall Street, by Wall Street and for Wall Street.” Lease was instrumental in creating the People’s Party, better known as the Populists, which shocked the nation by winning 91 seats and control of the Kansas State Legislature in 1890.

A growing discontent among working people was not confined to the nation’s cities. Farmers in the Midwest — whose wheat, corn, oats and rye fed the world — were working dawn until dusk for meager returns. In Kansas, Mary Elizabeth Lease, a firebrand and feminist, criss-crossed Kansas advocating for farmers’ rights. “It is no longer a government of the people, by the people, and for the people,” she proclaimed, “but a government of Wall Street, by Wall Street and for Wall Street.” Lease was instrumental in creating the People’s Party, better known as the Populists, which shocked the nation by winning 91 seats and control of the Kansas State Legislature in 1890.

Success in Kansas swept the country. Populist farmers joined labor unionists, Western miners and black professionals and farmers from the South, creating a third political party. They put forward radical and untested ideas to bring power back to the people through public ownership of railroads and utilities and a federal income tax.

As the Populists made gains, clashes between business owners and workers intensified. When Andrew Carnegie attempted to cut wages at his steel plant in Homestead, Pennsylvania, union leaders fought back. During the ensuing lockout and strike, workers and private armed guards clashed in armed conflict, leaving 16 dead and more than 150 wounded. The government then stepped in to align itself with Carnegie and enabled him to crush the union.

Throughout the Gilded Age the economy grew at a furious pace, but financial markets were wracked by instability. On May 4, 1893, Wall Street investors saw much of the nation’s wealth disappear. As many as a million workers lost their jobs. People starved to death. A year later, the nation was still reeling when Jacob Coxey, a Midwestern businessman, announced America’s first march on Washington to urge the government to take responsibility for out-of-work men. His idea caught fire and sparked a pilgrimage of thousands of men across the country.

Heading into the presidential election of 1896, class tensions appeared to be at a breaking point. The newly wealthy watched in fear as former Nebraska congressman William Jennings Bryan rallied working people behind the Democrats in his run for the presidency on a Populist platform that supported a federal income tax on the rich and the breakup of powerful monopolies. “There are those who believe that if you will only legislate to make the well-to-do prosperous, their prosperity will leak through on those below,” said Bryan. “The democratic idea, however, has been that if you legislate to make the masses prosperous, their prosperity will find its way up through every class which rests upon them.”

Bryan faced off against the Republican nominee, former congressman and Ohio governor William McKinley, a longtime friend of business. McKinley’s campaign, backed by the considerable cash of men like Carnegie and Morgan, blanketed the country with posters and leaflets promising stability by maintaining the status quo. “The real question was, and sort of the wild card at this point was, ‘What are urban workers going to do? Are they going to vote along class lines and join forces with the farmers?’” says historian H.W. Brands. “So this is the moment of truth for this emerging working class.”

Bryan faced off against the Republican nominee, former congressman and Ohio governor William McKinley, a longtime friend of business. McKinley’s campaign, backed by the considerable cash of men like Carnegie and Morgan, blanketed the country with posters and leaflets promising stability by maintaining the status quo. “The real question was, and sort of the wild card at this point was, ‘What are urban workers going to do? Are they going to vote along class lines and join forces with the farmers?’” says historian H.W. Brands. “So this is the moment of truth for this emerging working class.”

On election day, 80 percent of the population voted. Bryan carried the South, the Great Plains and much of the West, but McKinley won the presidency, supported by factory workers and the heavily populated region from the Great Lakes through the Northeast. “During the Gilded Age, capitalism gained greater and greater control of American life,” explains Brands. “The essence of democracy is equality. Everybody gets one vote. The essence of capitalism is inequality. Rich people are much more powerful than poor people.”

“The question of wealth versus people ballooned in the Gilded Age,” concludes historian Nell Irvin Painter. “Do our governments represent wealth or do they represent people? This is a fundamental issue, which is with us today.”