News

OU Develops Simulation to Train Opioid Overdose Response

By: Aaron Payne

Posted on:

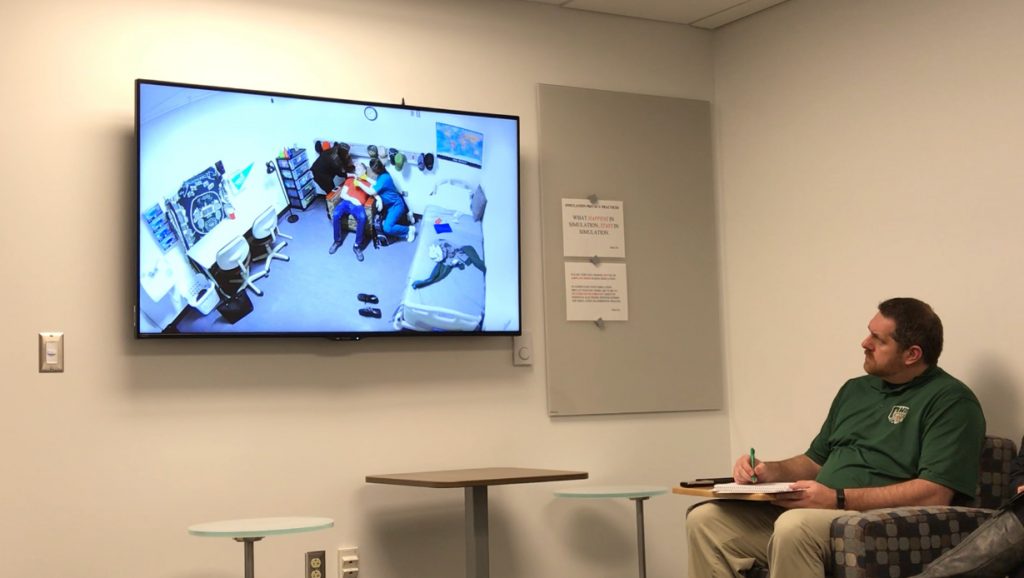

In a mock dorm room, an actor sits slumped over in a chair, simulating the effects of a heroin overdose. Two students walk in and launch into a series of actions that end with them “reviving” him with a practice dose of NARCAN, a brand name version of the overdose reversal drug naloxone.

The students and faculty at Ohio University’s College of Health Sciences and Professions who created this simulation hope it will teach people how to save a life if they encounter a real overdose.

Assistant Professor Sherleena Buchman found a need for this type of program during her House Supervisor role in her ongoing practice as a nurse.

“We’re seeing people that are being dropped off at the doorstep or left in their cars at the emergency room entrance that have had opioid overdoses because people don’t want to seek help,” she said.

With a background in simulation and virtual reality research, Buchman approached her Interprofessional Grand Rounds class about developing a program with the goal to train anyone to respond to an overdose.

“We teach people how to do the heimlich. We teach them how to do CPR,” Buchman said. “Why not teach them how to give NARCAN to save a life?”

The dorm room simulation was presented Monday to the public, along with several other simulations and demonstrations.

Another simulation presented a scenario in which a multi-disciplined team educated a parent in the emergency room after their child accidentally overdosed on opioids.

Those in attendance Monday were also given a demonstration of how to use the NARCAN nasal spray on someone they suspect is suffering from an overdose.

“It may not be the first step for prevention. But it is a first step to save a life,” Buchman said.

NARCAN is not a treatment or cure for an opioid use disorder. But it is increasingly being utilized as a tool to combat the addiction crisis nationwide.

U.S. Surgeon General Jerome M. Adams recently released a public health advisory “recommending that more individuals, including family, friends and those who are personally at risk for an opioid overdose, also keep [naloxone] on hand.”

In Ohio, 4,329 Ohioans died of fatal overdoses in 2016 –the last year statewide numbers were available– according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Training more people to be able to respond to overdoses might reduce the number of fatal overdoses, according to Buchman. She and the students want to continue developing the simulations and expand their reach.

“Finding ways that we can lead the education,” Buchman said.